PRIMROSE, James.

AGAINST QUACKS AND HEALERS

Popular errours. Or the Errours of the People in Physick.

London, W. Wilson for N. Bourne, 1651£7,500.00

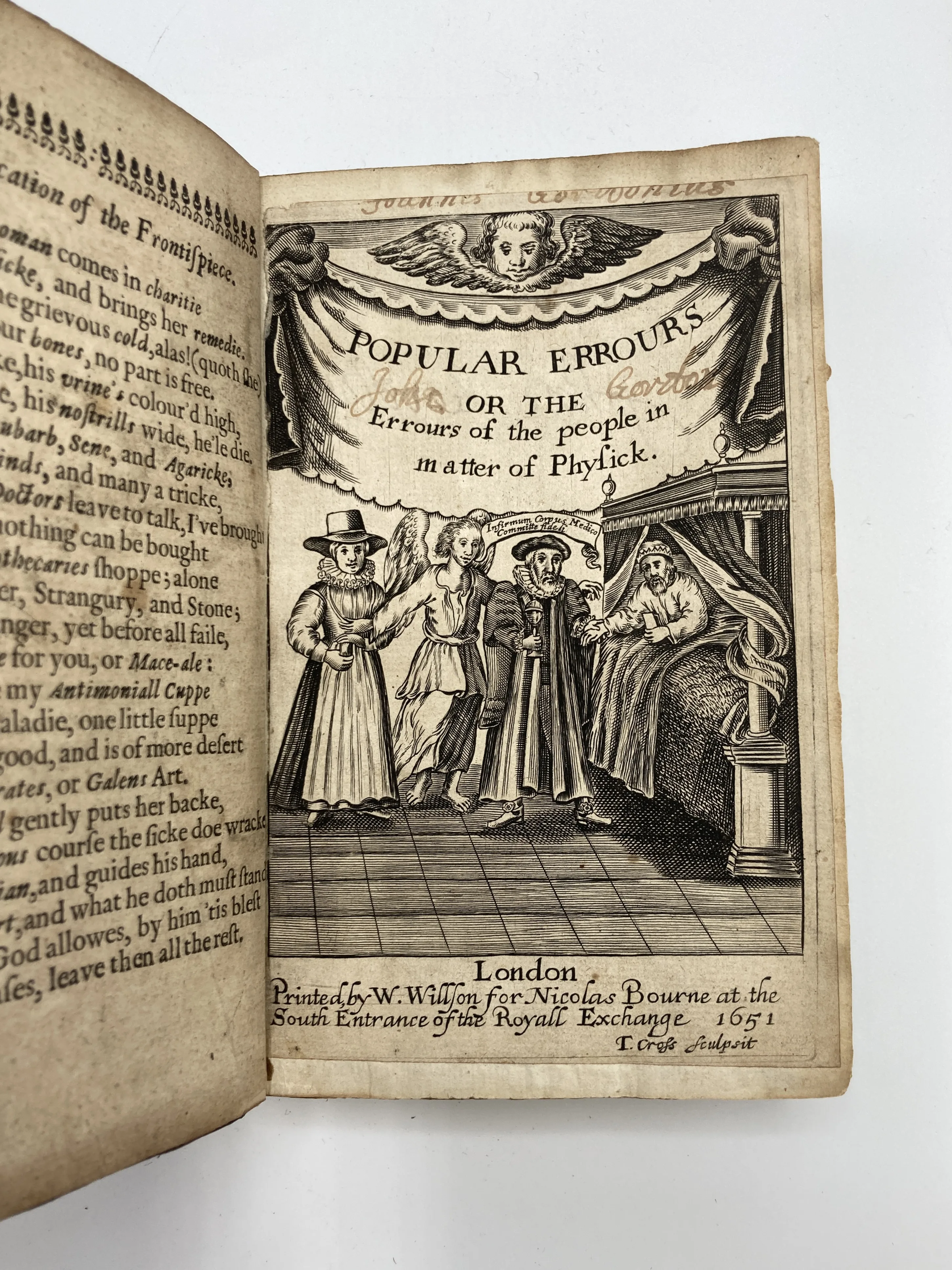

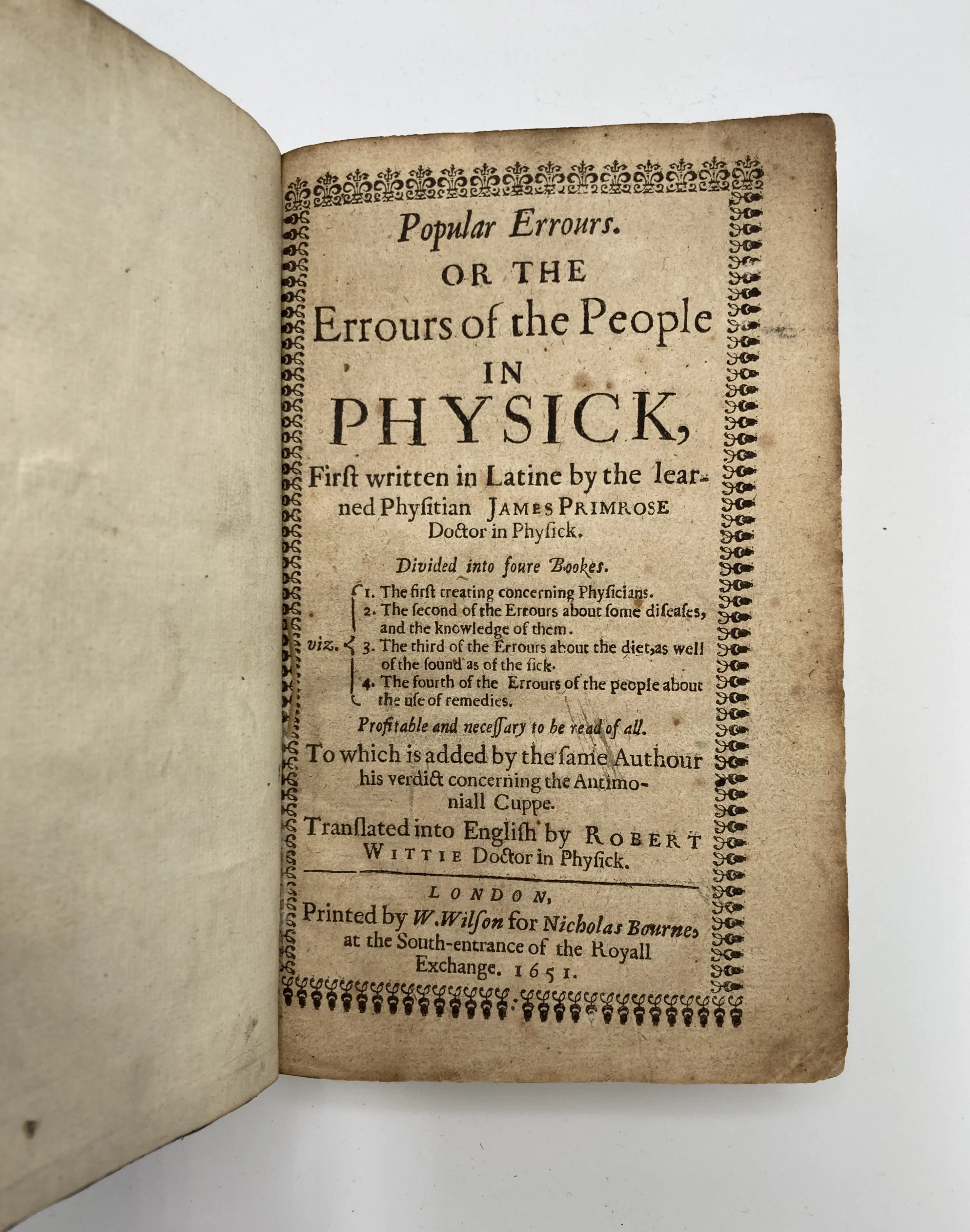

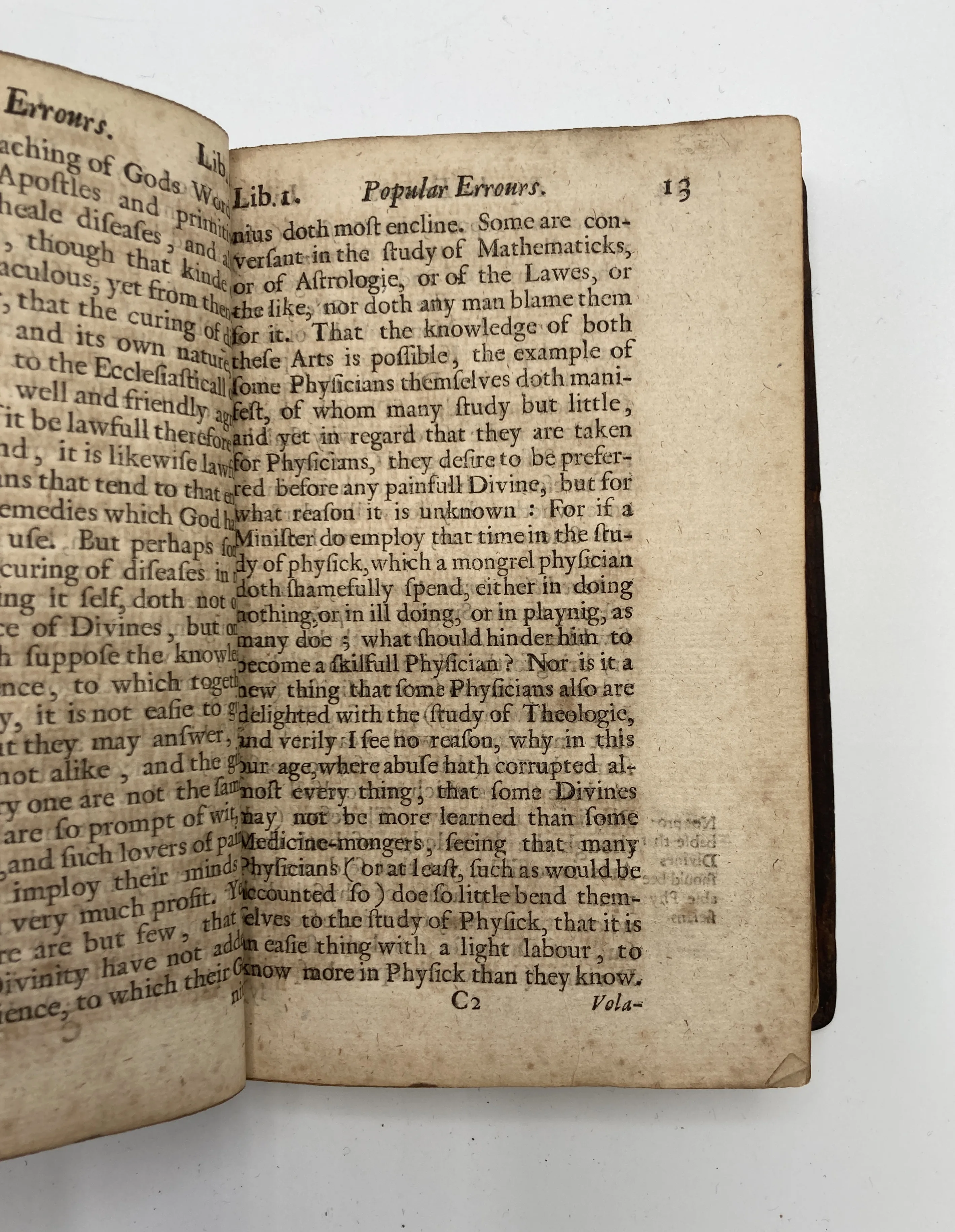

FIRST EDITION thus. 8vo. pp. [24], 461, [15]. Roman letter, little Italic. Added engraved title (mounted), printed title within typographical border, decorated initials and ornaments. Light browning, the odd marginal finger-mark. A good, clean copy in contemporary sheep, C19 reback and eps, double blind ruled, gilt-stamped centrepieces of the Society of Writers to the Signet to covers, joints and corners repaired, minor leather loss to upper cover. Contemporary or near contemporary autographs ‘Johannes Gordonius’ (trimmed) and ‘John Gordon’ to title.

A good copy of the first edition in English of this important work, criticising unqualified doctors and lay physicians. This translation by Robert Witty includes two commendatory poems by Andrew Marvell who, like Witty, was patronised by the Fairfax family. James Primrose (d.1659) trained at Bourdeaux and Oxford, and was admitted to the Royal College of Physicians having among his examiners William Harvey. First published in Latin in 1638, ‘Popular errours’ is entirely devoted to debunking the effectiveness of numerous popular remedies used at the time, especially in the countryside, where trained doctors were generally unavailable. Primrose suggested that only trained physicians and surgeons really knew the discipline, and that lay people (‘mongrell-Physicians’) ‘ought not so rashly and adventurously intermeddle with them’. Primrose sought to establish a ‘professional ethos’, inspired by practices advocated by the RCP (Bennett, p.19). ‘Popular errours’ begins with a discussion of trained doctors, followed by several chapters on healers who shouldn’t practise. These include doctors’ assistants, poor scholars who learn from their master and end up practising unlicensed to earn money, physician-clerics (who treat their parishioners for money), women (‘especially busied about surgery, and that part chiefly which concerns the cure of tumours and ulcers’), mountebanks or charlatans (who sold special antidotes against poisons, balsams and ointments), and almanac-makers. Primrose advocated that physicians should also know about surgery, and examined whether they should also be trained in the art of apothecaries. There follow sections on physicians who base their diagnosis only on urine (to the correct interpretation of which a few sections are later devoted) and the pulse; who promise easy treatments of the French pox (syphilis); or who flee during a plague to keep themselves safe (with a reference to Hippocrates’ oath). Numerous sections are devoted to mistaken diagnoses, such as that a man’s illness might be due to his wife being pregnant, that gold boiled in broth will treat consumption, and that tobacco might protect one from the plague. Primrose also suggests that the quantity of blood let should be reckoned in ‘measures’, not ‘ounces’ or ‘pounds’. The last section is devoted to the alchemical remedy called ‘antimonial cup’ and its uses and abuses. Made of mercury, sulphur and arsenic, it caused violent purging reactions which debilitated even the strongest patients, so it had to be prepared very carefully. A most interesting snapshot of popular medicine in mid-C17 England.

ESTC R203210; Wing P3476; Krivatsy 9289; Wellcome IV, p.438; Osler 3736. Not in Heirs of Hippocrates. L. Bennett, Rhetoric, Medicine, and the Woman Writer, 1600-1700 (2018).In stock