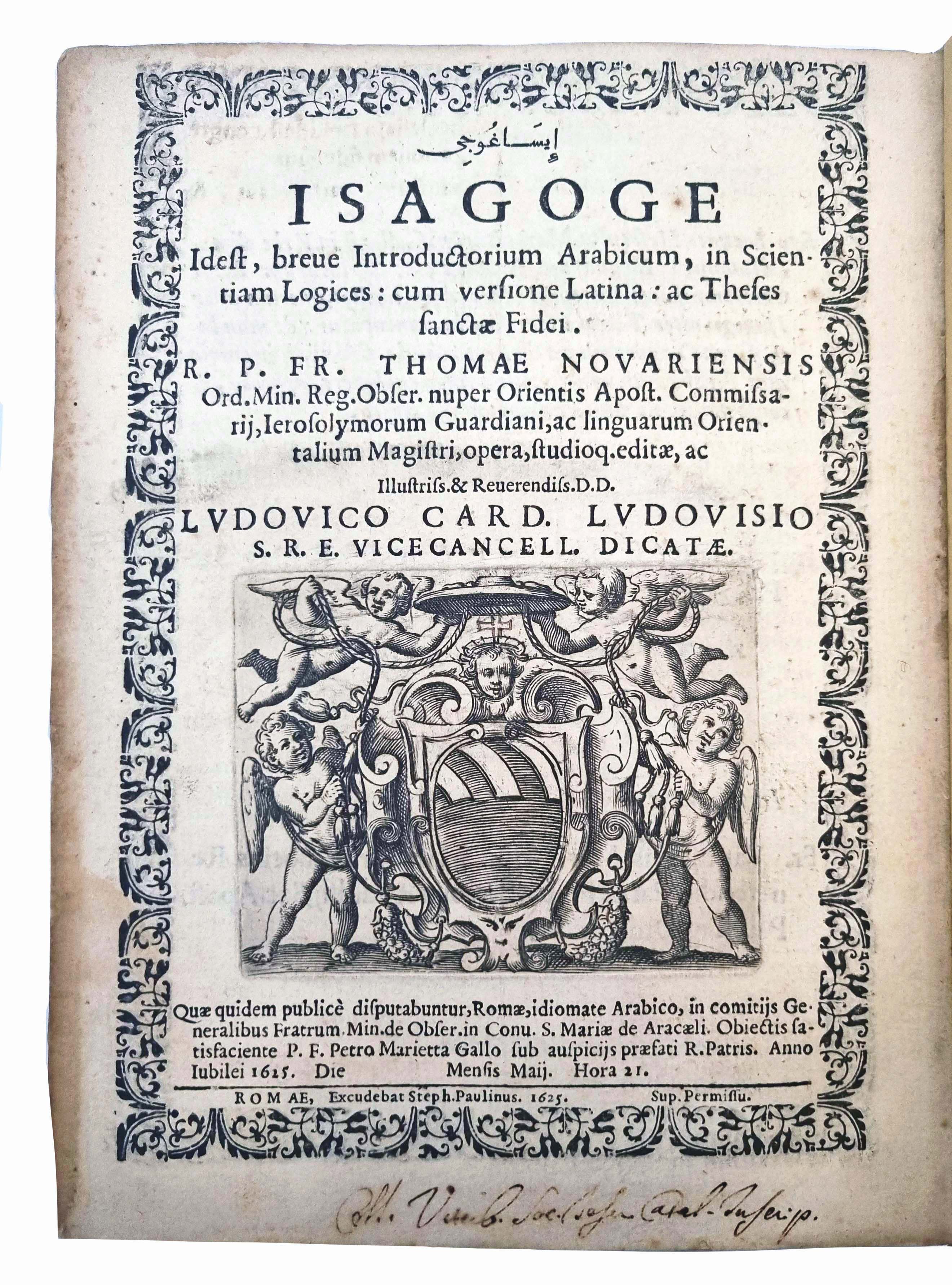

OBICINI, Tommaso; AL-ABHARĪ, al-Mufaḍḍal ibn ʿUmar.

ARABIC LOGIC

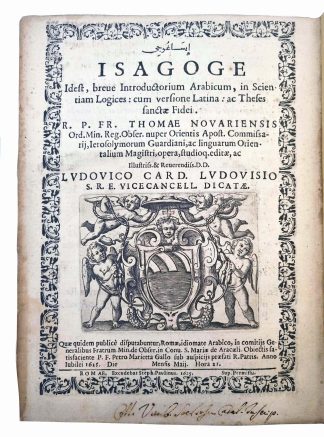

Īsāghūje. Isagoge id est, breve introductorium Arabicum.

Roma., Stefano Paolini., 1625.£4,500.00

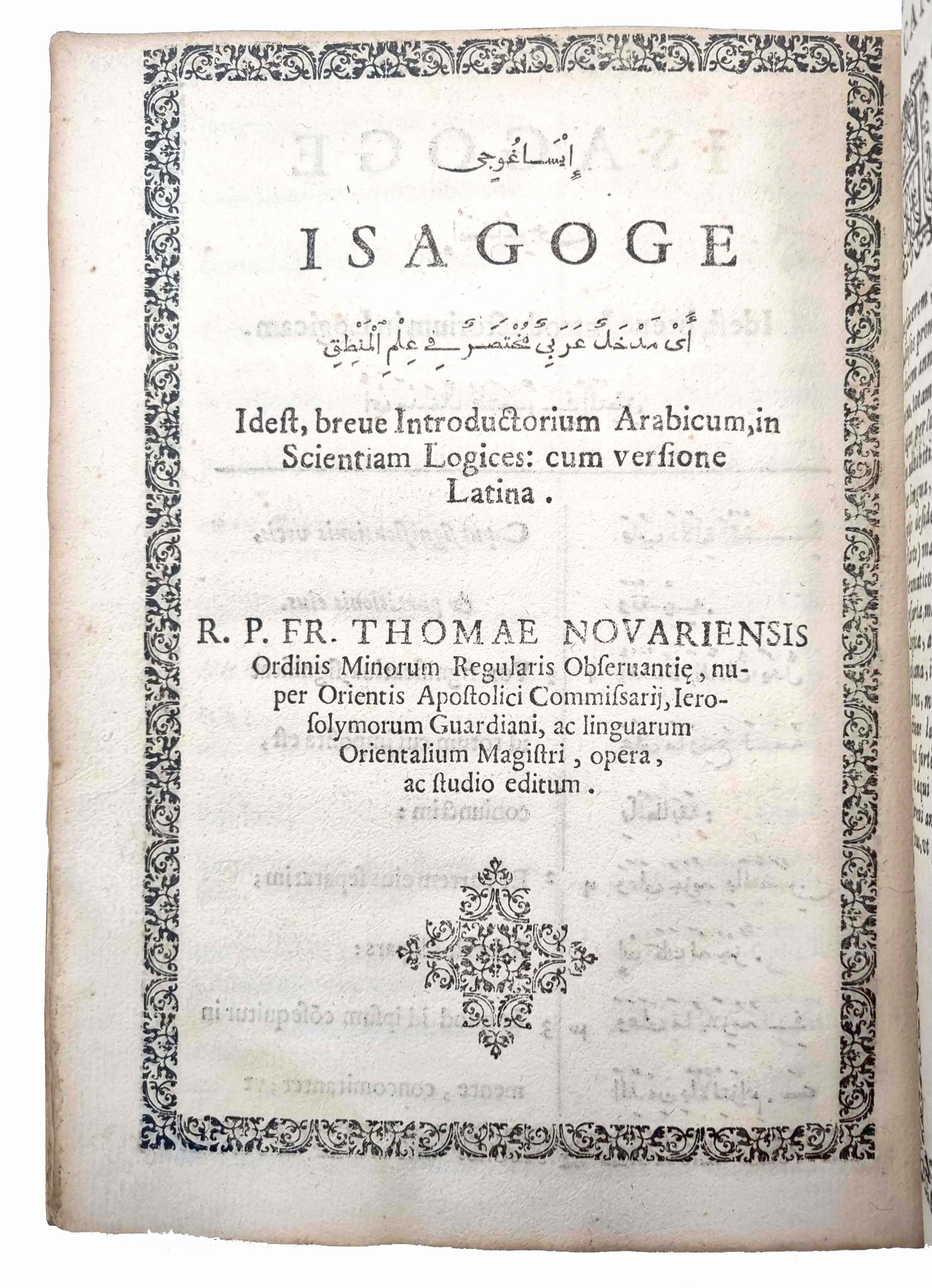

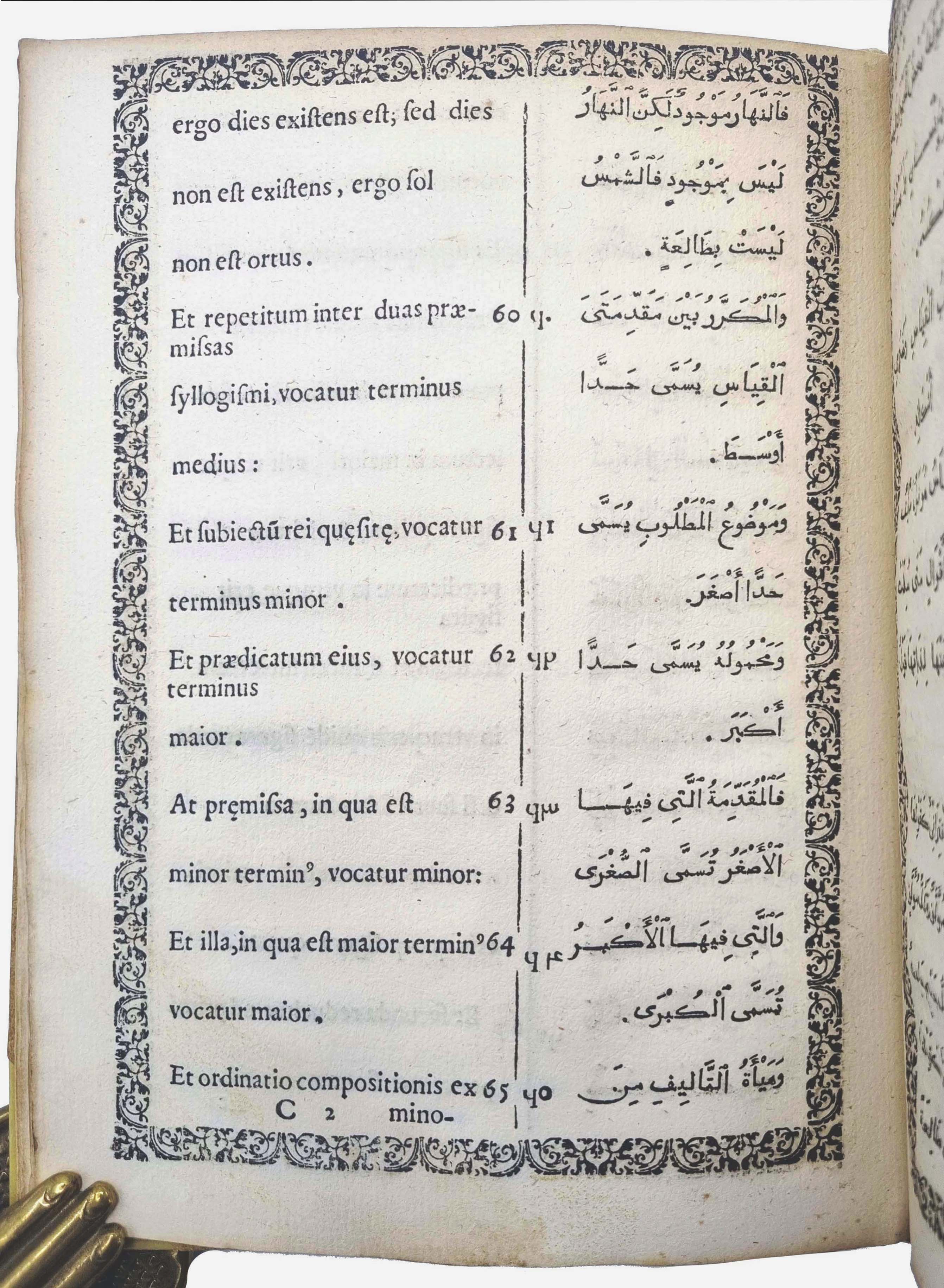

FIRST EDITION. 4to. ff. [22], π² A-E⁴. Arabic (vocalised) letter, with Roman, double column. All pages within typographical border. Engraved vignette with arms of Cardinal Ludovisi to title, decorated initials. Very slight age browning, upper edge trimmed a bit short. A very good, clean copy in modern vellum over paper boards. C17 ms ‘Coll.[egium] Viterb.[ensis?] Soc.[ietatis] Jesu Catal.[ogo] Inseritus’ at foot of title.

A very good, clean copy of the first edition of this influential C13 Arabic introduction to logic by Mufaḍḍal ibn ʿUmar al-Abhārī, here in its first edition of the first Latin translation by Tommaso Obicini. The imprimatur states that the Arabic text and its Latin rendering were reviewed and approved by Joannes Hesronita, of the Maronite College in Rome. According to the subtitle, this work was publicly discussed – in Arabic – in Rome in 1625, at the general Council of the Franciscans in Santa Maria in Aracoeli, probably as a practical linguistic exercise for future missionaries.

Al-Abhārī (d.1262/5) was a major Persian polymath, who studied theology under al-Rāzi and astronomy under al-Mawṣilī, and became an influential thinker in Muslim schools. Tommaso Obicini (1585-1632) was a Franciscan and specialist in Middle Eastern and Semitic languages. He translated numerous Arabic texts into Latin, and spent time in the Franciscan missions in Palestine, Syria and Lebanon. When he translated ‘Isagoge’, he was professor of Arabic at the monastery of San Pietro in Montorio, in Rome, a centre for Arabic studies.

‘Isāghūje fi al-manṭiq’ is an introduction to logic, inspired by Avicenna and al-Razi’s ideas, widely used as a textbook in the medieval Muslim world. (It is sometimes considered an offshoot of Porphyry’s ‘Isagoge’, a commentary on Aristotle’s ‘Logic’, but there are few significant similarities, beside the title.) It begins with a discussion of how humans give meanings to things – from the use of communication (verbal and written) to the five universal categories – proceeding to the nature of definitions and sound argument. There are chapters on propositions (al-qaḍāīā), oppositions (at-tanāquṣ), conversions (al-’aks, i.e., the inversion of subject/predicate order), syllogism (al-qīās), demonstrations (al-barhān), argumentation (al-jadal), persuasion (an-naḥṭāba), and so on. The chapters provide concise definitions of all these topics as well as examples. ‘After the C12, logic (‘manṭiq’) became an integral part of the education of Muslim scholars, and continued to be studied at Colleges like al-Azhar in Cairo […]. Neoplatonic/Aristotelian “falsafa” had fallen into disrepute into many parts of the Islamic world, but logic was still considered useful as an “instrumental” science, without which one could not master jurisprudence or theology’ (Enc.Med.Phil., p.690). Appended to ‘Īsāghūje’ are ‘Theses fidei Sanctae’ (‘masāīlu l-iīmāni al-muqaddami’), a summary of the main tenets of the Catholic church on true faith. A scarce and important work.

Only HRC copy recorded in the US. USTC 4000559; Schurrer, Bib. Arabica, 405. Encyclopedia of Medieval Philosophy, vol.I (2010); Risse, Bibliographia logica, 1965. v.1, p.125.In stock