MORE, St. Thomas

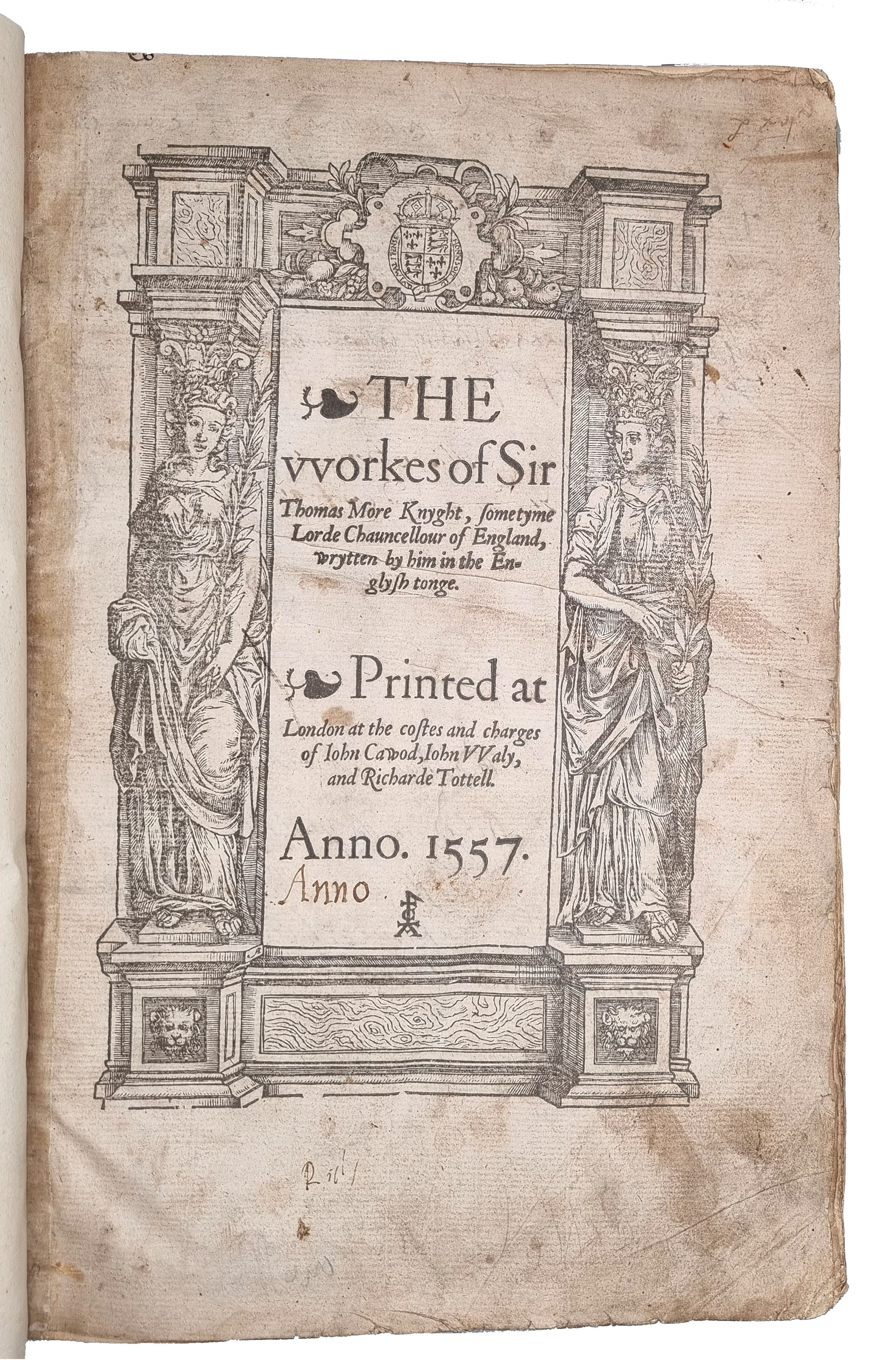

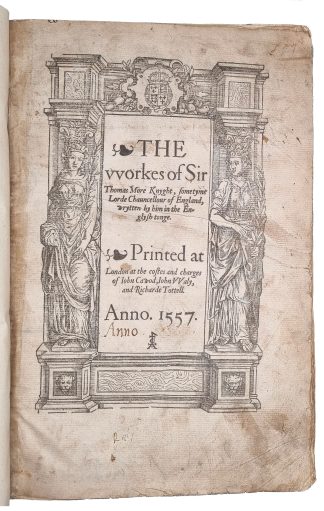

The vvorkes of Sir Thomas More Knyght, sometyme Lorde Chauncellour of England, wrytten by him in the Englysh tonge

London, at the costes and charges of Iohn Cawod, Iohn VValy, and Richarde Tottell, 1557£35,000.00

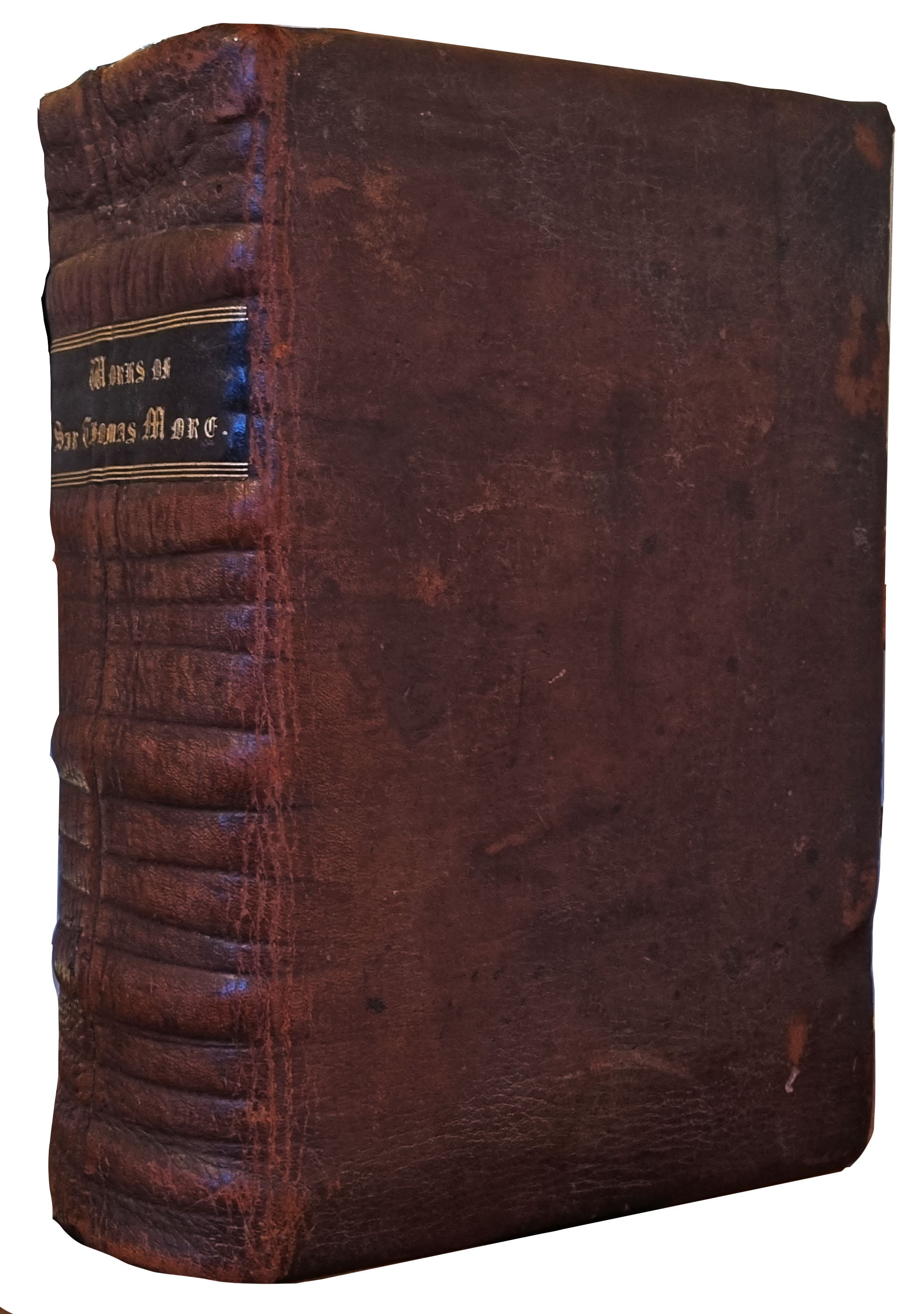

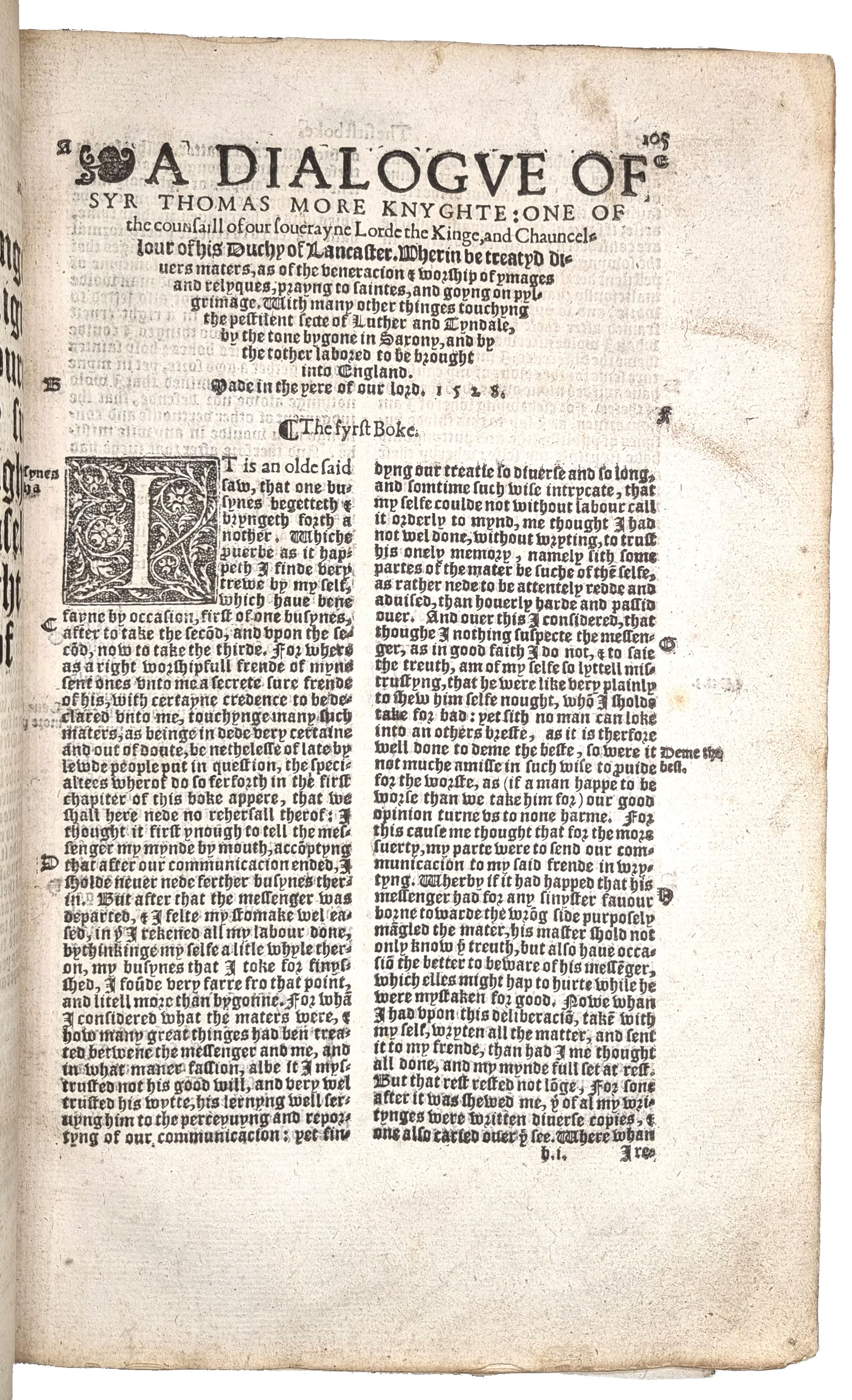

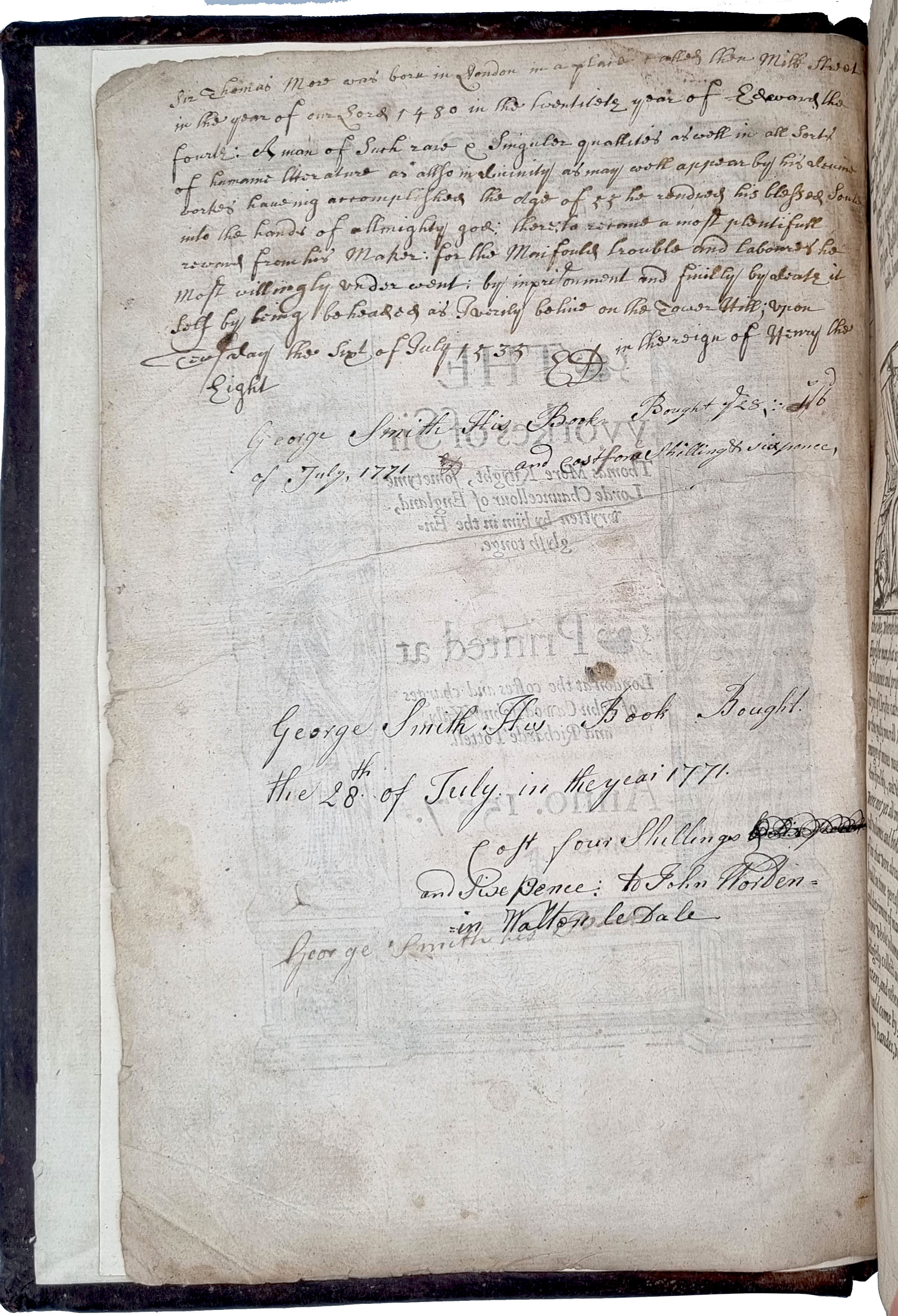

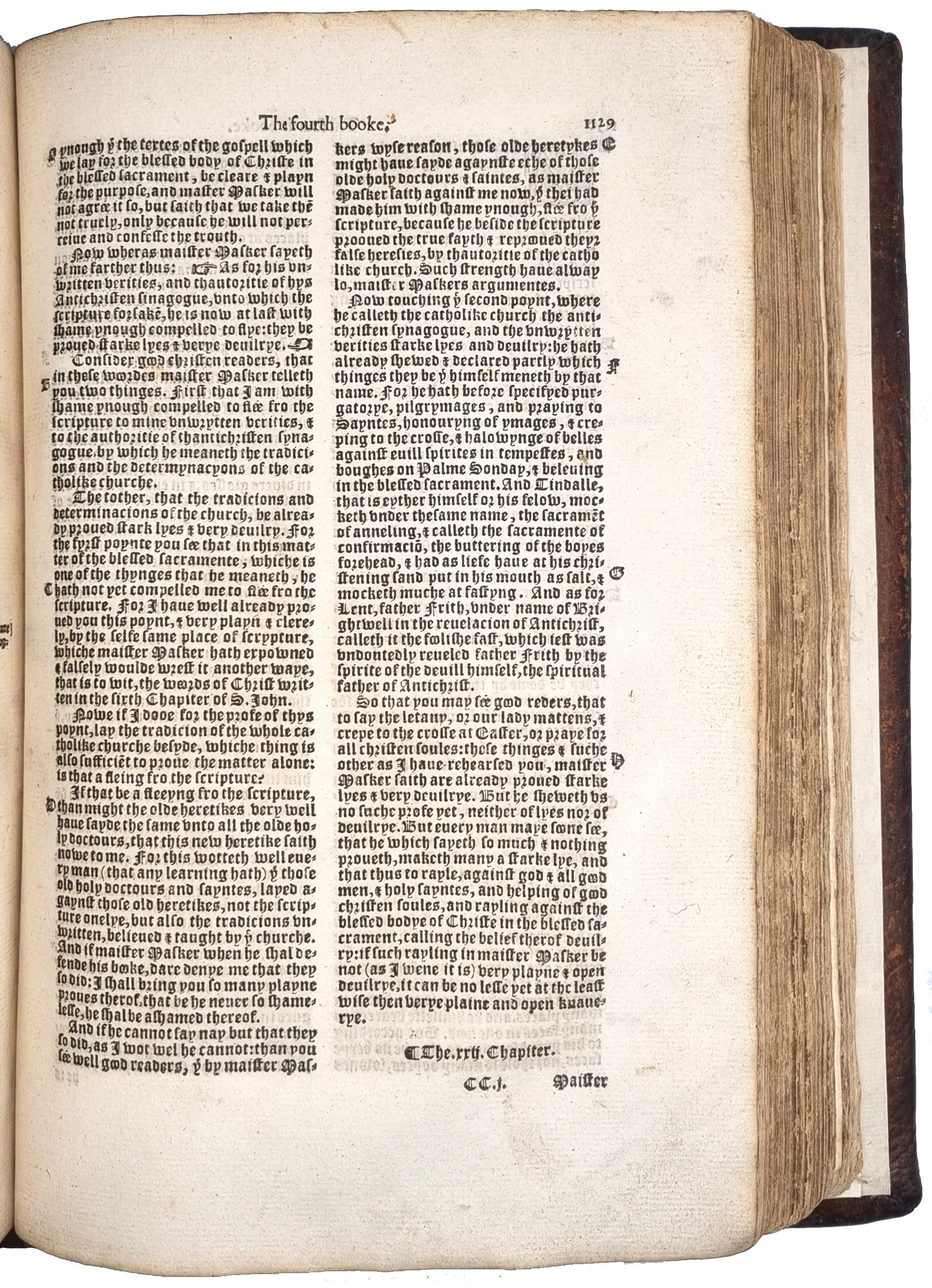

FIRST EDITION thus. folio. pp. [xxxvi], 88, 89-104 in columns, 105-1138, [ii], 1139-1458, [ii]. [[par.]¹ , [par.] , a-f , h-2z , A-2B , 2C (2C5+chi1), 2D-2Y , 2Z .] lacking final blank. Black letter, some Italic. Title within fine woodcut border, royal arms at head, large historiated, floriated and white on black criblé woodcut initials, note on the life of Thomas More in early English hand on verso of title, “George Smith His Book Bought the 28 of July 1771 and Cost one Shilling & six pence …Cost foure shillings and sixe Pence: to John Worden in Walton le Dale” below. Light age yellowing, title a little dusty and stained, thumb marks and minor marginal stains to first leaves, B4 with tear, repaired in margin, a few other small marginal tears, some mostly marginal dust soiling, the odd thumb mark and minor spot or stain, light waterstain to upper margins of last few leaves. A good copy, crisp and on thick paper, with good margins, in early thick unpared ox-hide over probably original wooden boards, later black morocco label gilt on spine, endpapers renewed.

Exceptionally important first edition of the works of St. Thomas More in English, edited by his nephew, William Rastell, arranged in chronological order with marginal notes and a dedication to Queen Mary; the first collected edition of any of More’s works. “Thomas More was called by his contemporary John Colet “the one genius of Britain.” Coming as he did at the end of the Middle ages and at the beginning of the modern era, he was a great transitional figure, passionately devoted to the good things of medieval Europe and yet an enthusiastic partisan of the New Learning. He was the warm friend and supporter of Erasmus, and was in close touch with all the important figures in England of his time. With a style inherited, as R.W. Chambers points out, from the great English devotional writers, he immensely broadened the scope of English prose. Still his work, although it includes as often-reprinted classic in the Utopia, remains in large part inaccessible to the modern reader. The English writings have lain dormant in the black-letter of the 1557 folio, printed by his nephew William Rastell. Among the many items in that volume is an important text of the History of Richard III, based, according to Rastell, on a copy in More’s own hand. (the text printed by Grafton in his edition of Hardyng’s chronicle (1543) is corrupt.) The modern reader knows this History as it is reflected in Shakespeare’s Richard III, which is based upon it.” David R. Watkins. ‘The St. Thomas More Project’ The Yale University Library Gazette. Vol. 36, No. 4.

“Given the conditions that More faced in the Tower of London during his last year it is all the more remarkable that he continued his writings. Towards the end, when paper and pen had been taken from him, he still managed to write letters in charcoal to the family. His Treatise on the Passion and the Latin version, Exposito passionis, give a vivid account of Christ’s last hours before his death on the Cross, and his Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation is sometimes regarded as his finest work in English. On his death all his works and papers passed to his daughter Margaret (died 1544) and then to a nephew, William Rastell, who compiled the complete English Works in 1557. More’s Latin works were collected and printed partly in Basel under the title Lucubriationes in 1563 and more fully in Louvain in 1565–66 under the title Opera omnia.” Keith Watson. ‘Sir Thomas More.’

“More’s witty and ironic presentation of Richard and his villainy seem to have been particularly influential, as were the parallels he drew between theatre and politics: ‘And so they said that these matters bee kynges games, as it were stage playes, and for the more part plaied upon scaffolds’ (p. 66).” British Library.

“Thomas More’s brother-in-law, John Rastell, was one of England’s earliest printers, and he became the printer and publisher of More’s important work of religious controversy, the Dialogue Concerning Heresies, in 1529. After this, up to the time of More’s death in 1535, John Rastell’s son William carried on the work of printing and publishing More’s voluminous works of controversy, in close association with the author. And so, appropriately, William Rastell became the editor and publisher of his uncle’s collected English works, as he tells us in his dedication to Queen Mary, explaining that he “did diligently collect and gather together, as many of those his works, books, letters, and other writings, printed and unprinted in the English tongue, as I could come by, and the same (certain years in the evil world past, keeping in my hands, very surely and safely) now lately have caused to be imprinted in this one volume.” … From the great series of last letters written from the Tower, preserved by More’s family, and first published by William Rastell at the very end of his 1557 folio, we learn all we will ever know about the inner drama of that famous prisoner in his last days. The letters are numerous and long, except for the few brief and pathetic letters that More and Rastell tell us were “written with a coal” .. The greatest single contribution of the 1557 folio to history is, I believe, the arrangement, annotation, and publication of these letters, which gave to generations following the complex portrait of More that has come down to our own day” Louis L. Martz. ‘University of Rochester Library Bulletin: The Workes of Sir Thomas More Knyght. Volume XXXVI.’

ESTC S115047. STC 18076. Pforzheimer, 743. Gibson. 73.In stock