MOLITOR, Ulricus

THE FOUNDATION IMAGERY OF WITCHCRAFT

De laniis et phitonicis mulieribus

Constance [Basel], [Michael Furter], 1489 [i.e. ca. 1495]£95,000.00

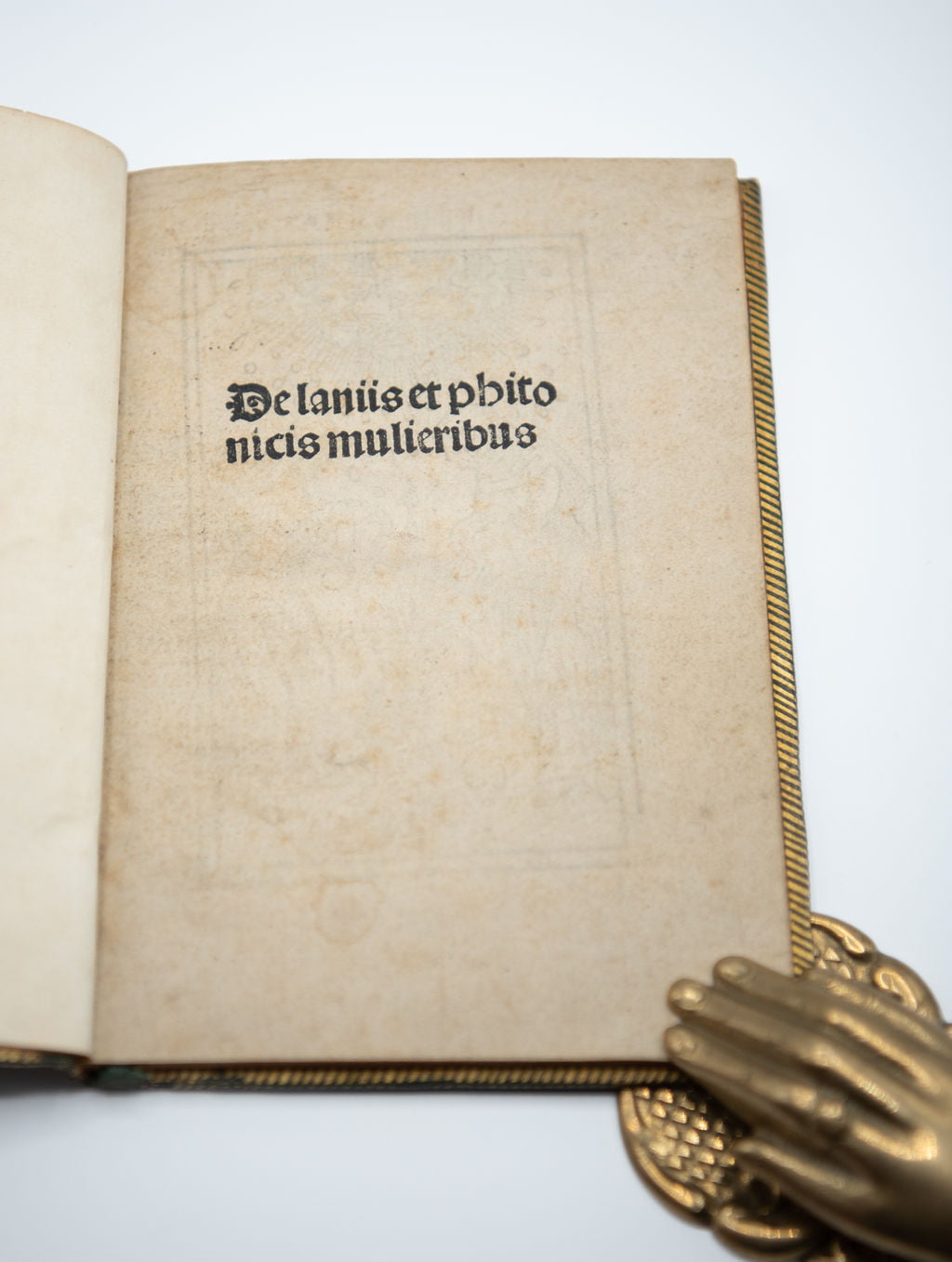

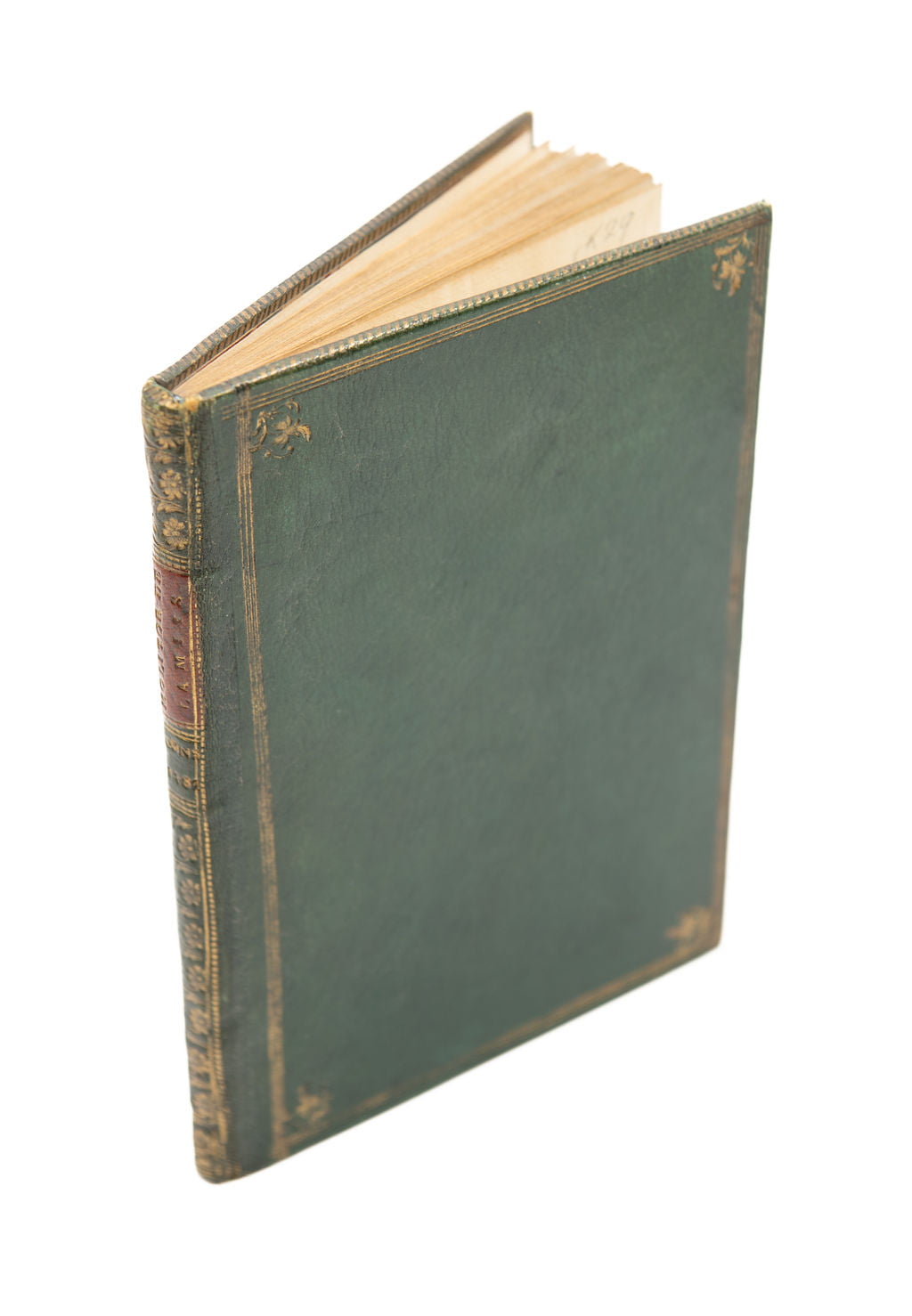

4to. 30 unnumbered leaves. a–c , d . Gothic letter. Capital spaces, seven fine full page woodcut illustrations within double ruled border, manuscript medical? recipe in early C16th hand on blank verso of last, another note in the same hand on recto of c8, ‘Millot de Sombernon’ in near contemporary hand at head of blank verso of last, ‘vendu 21 r mac-carthy’at head of front fly, C19th printed shelf label on pastedown, Guy Bechtel’s bookplate below with his motto ‘in carcere meo liber.’ Very light age yellowing, the very rare minor spot or mark. A fine well margined copy, crisp and clean in lovely C18th French green morocco, in the style of Derome, covers bordered with a triple gilt rule, fleurons gilt to corners, flat spine with repeated gilt fleurons within double gilt border, red morocco label gilt, edges and inner dentelles gilt, all edges gilt, joints very expertly (invisibly) restored.

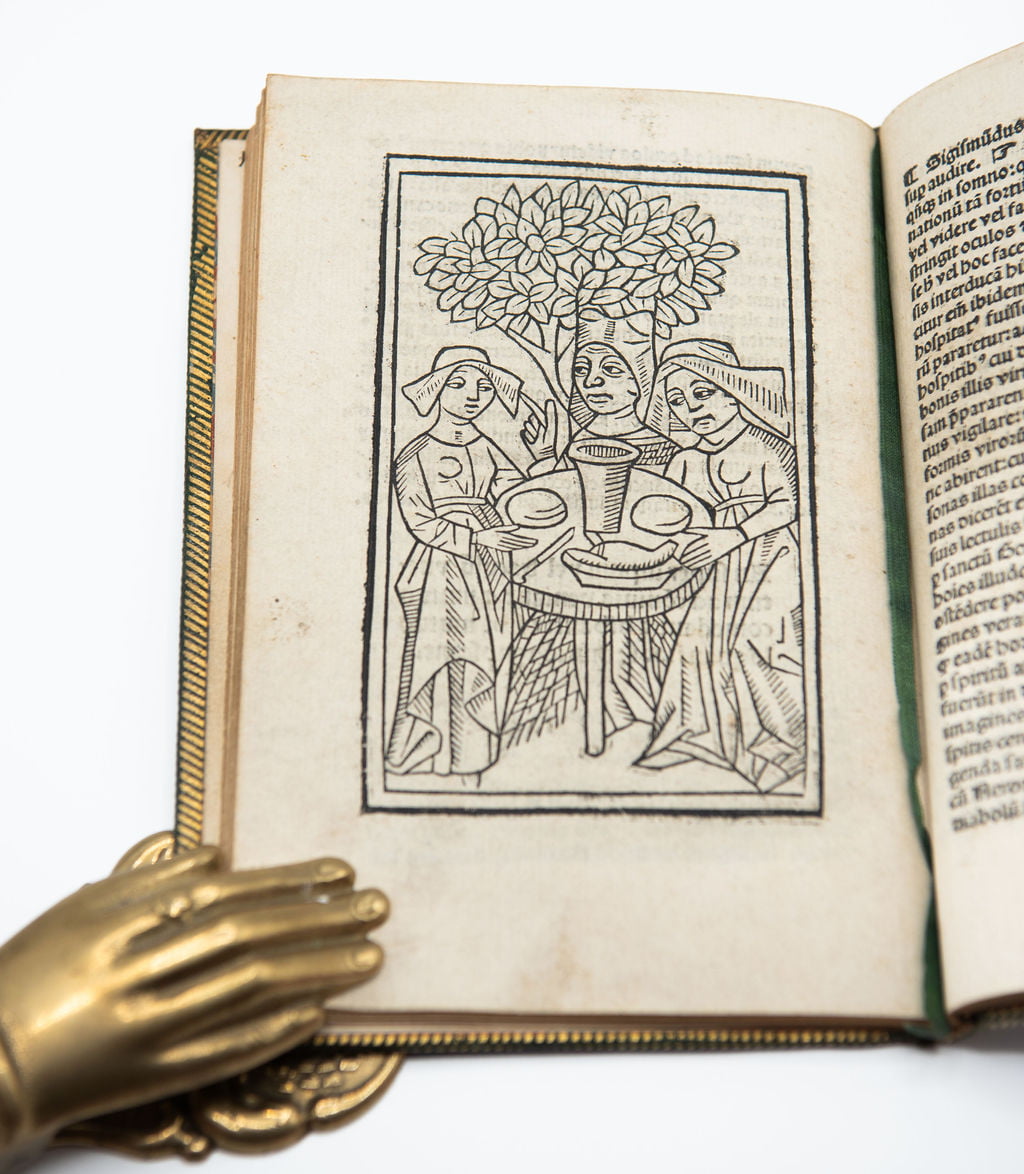

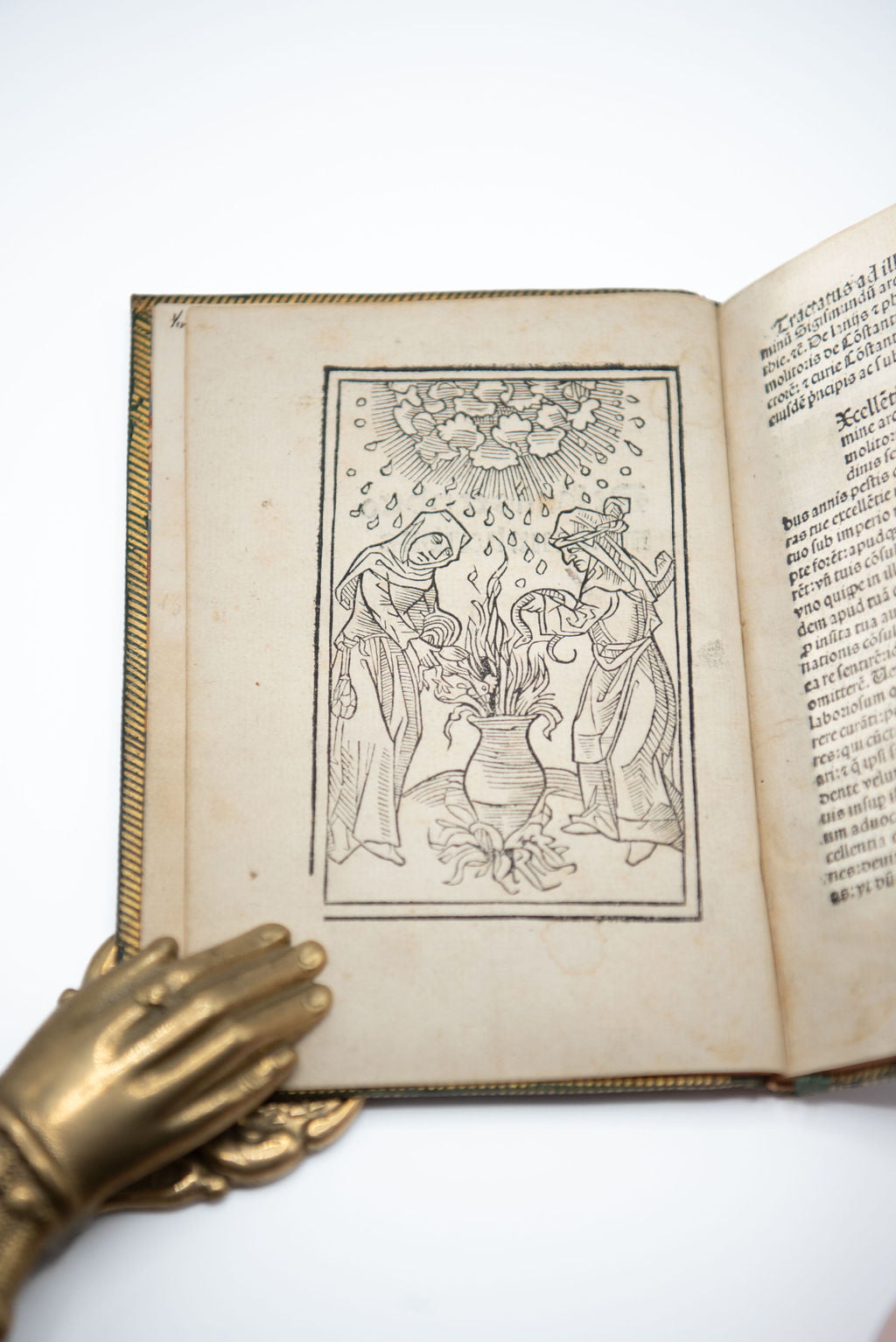

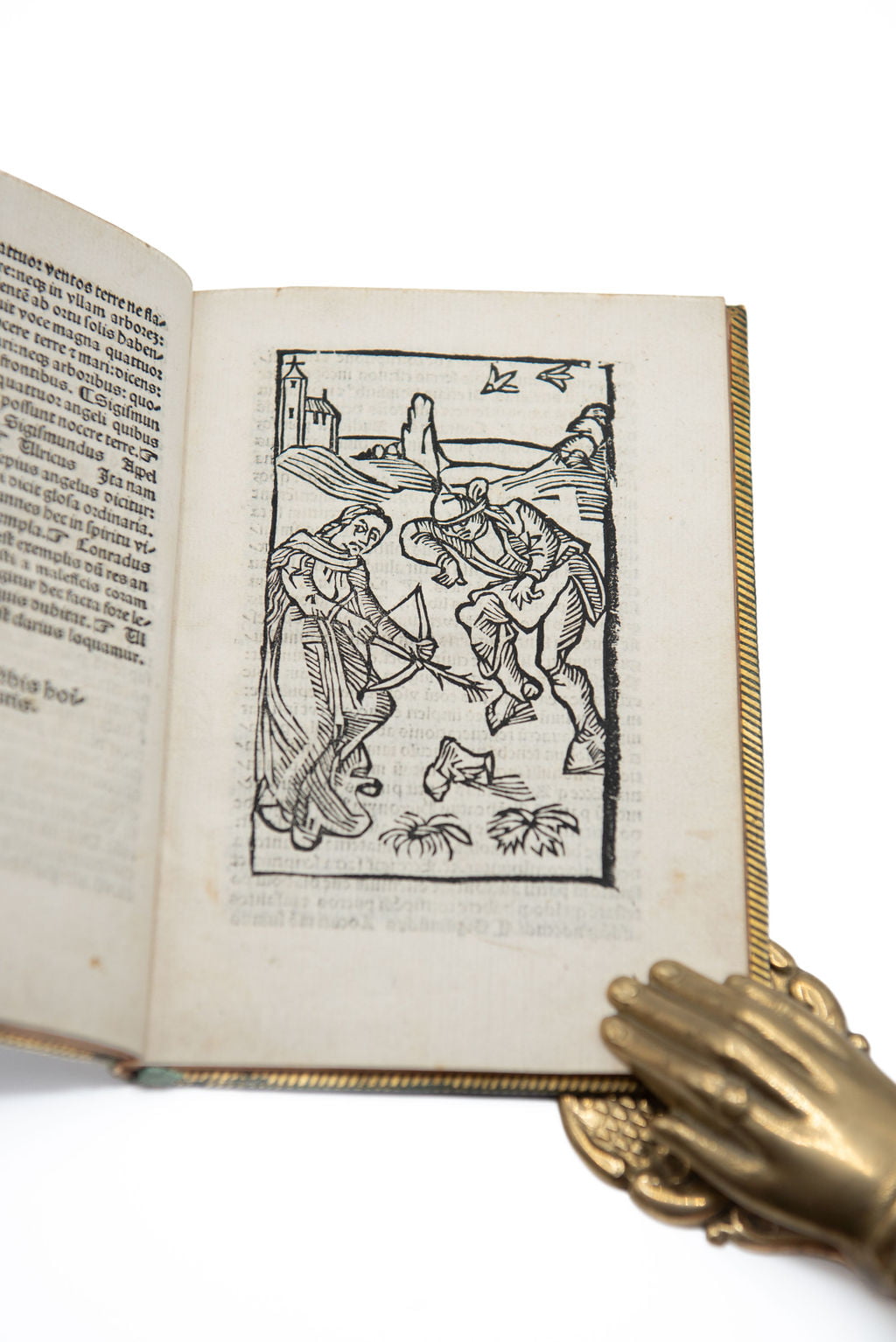

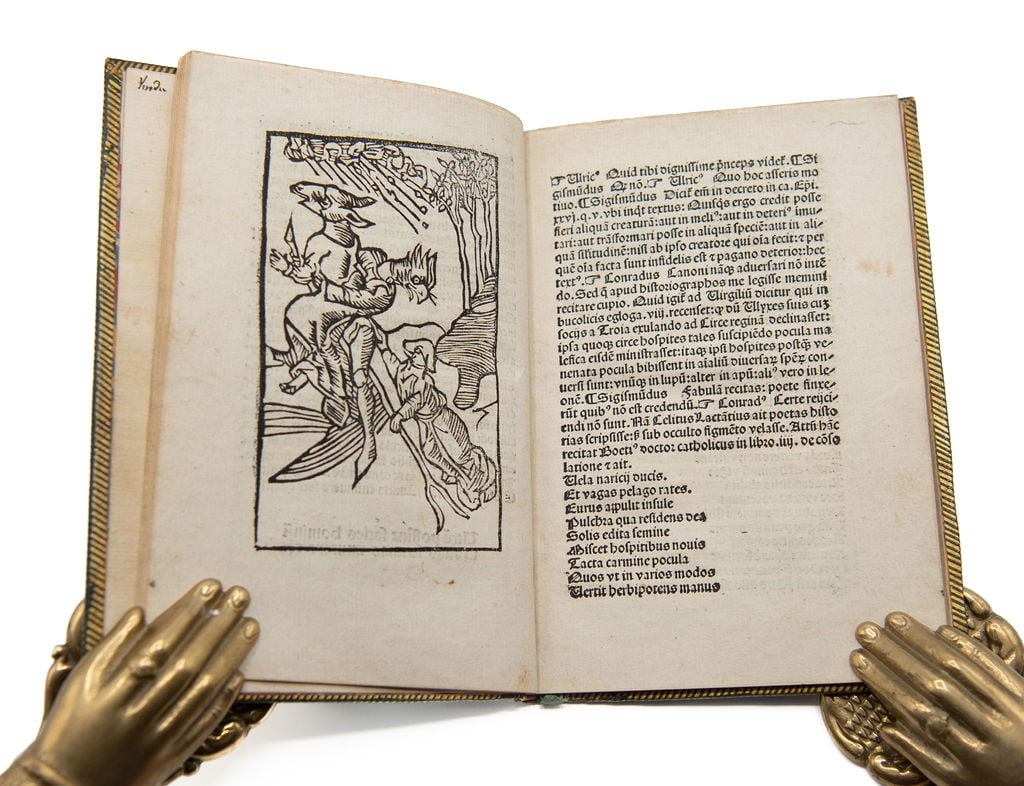

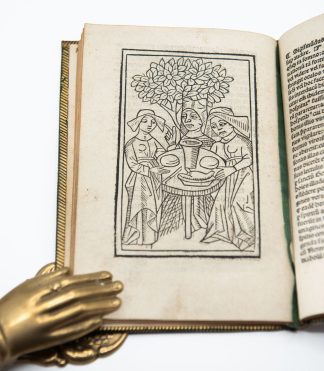

A beautiful copy of this exceptionally rare and important text, the first and most important illustrated work on witches and a work that has defined the image of witches to this day. The ‘De Lamiis,’ was first published in 1489 with the same series of iconic woodcuts. It is one of the earliest printed works on witchcraft, and contains the first ever illustrations of witches. This, probably the first Basel edition, is beautifully printed in a fine gothic letter in thirty-two lines and very finely illustrated with seven stunning woodcuts depicting witches and their activities. The first depicts two witches around a large pot, one throwing in a cockerel the other preparing to throw in a snake, the resulting brew creating a storm. The other blocks represent a lycanthropic scene of a wizard mounted on a wolf, the devil disguised as a bourgeois man corrupting a woman, the ensorcellment of a man by a witch firing a spell, witches transformed into animals flying on brooms, and a group of three witches around a table.

The book is written in the form of a dialogue between the author and the dedicatee, the Archduke Sigismund of Austria, who doubts the existence of witches. At a time when complete theories about witchcraft were yet to be established, the author defended belief in the powers of the Devil and his ability to trick the human mind. The woodcut depicting three witches together, eating and drinking beneath a tree, is typical of the format of the work. The title on the previous page to this woodcut reads “An super lupum vel baculum unctum ad convivia veniant et mutuo comedant et bibant et sibi mutuo loquantur ac se invicem agnoscant.” “Can [witches] come to feasts on a wolf or an anointed stick, eat drink, speak together and recognize one another?” The women are not doing anything other than eating but the image has become deeply anchored in the popular imagination, as it was used and referred to again and again in imagery and literature throughout the centuries, not least in Shakespeare’s ‘Macbeth.’

“The first tract on witches to be illustrated, 1489 – 94, was written by the lawyer Ulrich Molitor from Constance in 1484. He actually argues against the persecution of witches because he was sceptical of the value of confessions under torture. He did, however, believe that they were heretics and should be punished with death. In the illustrations, the witches are not characterised by any special dress or undress, implying that all women were capable of being witches. They look like ordinary housewives except in the ‘Flight to the witches’ Sabbath, when they are changed into animal shapes. Although the text speaks of the witches’ evil activities being a figment of their imagination, delusions inspired by the devil, the illustrations portray the effects of their malignant and harmful magical spells as real enough, e.g. a witch shooting at a man who tries to jump away, or witches making a brew, using a rooster and a serpent as ingredients, whilst hailstones come crashing down from the sky. Molitor certainly believed in the reality of their sexual intercourse with the devil.” ‘Picturing women in late Medieval and Renaissance art’ by Christa Grössinger.

“With the appearance of Ulrich Molitor’s ‘On Witches’ in 1488 – 89, the arguments of the Malleus were repeated in the literary format of a conversation among Molitor, Duke Sigismund of the Tyrol, and Sigismund’s minister Conrad Schatz, with a suite of seven remarkable woodcuts that for the first time offered related pictorial images of witches’ activities without any identifying physical or costume features attributed to witches – that is, some of the illustrations seem to depict ordinary women doing ordinary things.” Witchcraft in Europe, 400 – 1700. Alan Charles Kors, Edward Peters.

Several of the incunable editions of this book, including the first, have the date 10 January 1489 on the colophon. ISTC and GW date this edition to around 1495, though it is clearly earlier than Fairfax Murray (German, volume II, no. 289) also ascribed to Basel, Amerbach or Furter, which contains identical but broken versions of the same woodcuts, which Fairfax Murray dates to 1490.

Brunet cites this copy from the library of Reagh Mac-Carthy, the great Irish bibliophile (who found refuge in France, near Toulouse) in his sale of 1815 (I no. 1678). Justin ‘Reagh’ Mac-Carthy himself bought some of the major collections of the C18th, such as the library of Giradot de Prefond, and founded one of the richest personal libraries ever assembled, which included over eight hundred volumes of works printed on vellum. He also seems to have profited from the naïvety of the Librarian of Albi, Jean-François Massol, who was proud to have ‘swapped’ several precious medieval manuscripts with him for more ‘useful’ works such as Buffons’ 8vo. ‘Histoire Naturelle.’ The sale of his books at Paris in 1815 was one of the greatest of that century.

This copy then passed to the library of the Marquis of Germigny (sold 1939, no 13). In Mac-Carthy’s sale the work is recorded as being bound with the ‘Tractatus Utilissimus artis memorative’ by Matheoli Perusini (1498). This work was probably removed at some stage when the binding was restored. (As this work was only seven leaves, its removal did not affect the spine.) Its last owner was the great Scholar, author and bibliographer Guy Bechtel, author of the ‘Catalogue des Gothiques Francais 1476 – 1560.’ We have found no record of the early sixteenth century owner, ‘Millot de Sombernon.’

A lovely copy of a hugely important text with a very beautiful and most influential set of woodcuts, and most distinguished provenance.

Goff M798. (two copies only) Pell Ms 8166 (8095). GW M25157. ISTC im00798000. Brunet III, 1815 (citing this copy). Caillet, III, n°7630 (other editions). Fairfax Murray Ger., vol II no. 289 (another later edition with the same cuts).In stock