LENTULO, Scipione

SIR EDWARD COKE’S COPY

An Italian grammer; vvritten in Latin by Scipio Lentulo a Neapolitane: and turned in Englishe: by H.G

London, By Thomas Vautroullier, 1575£19,500.00

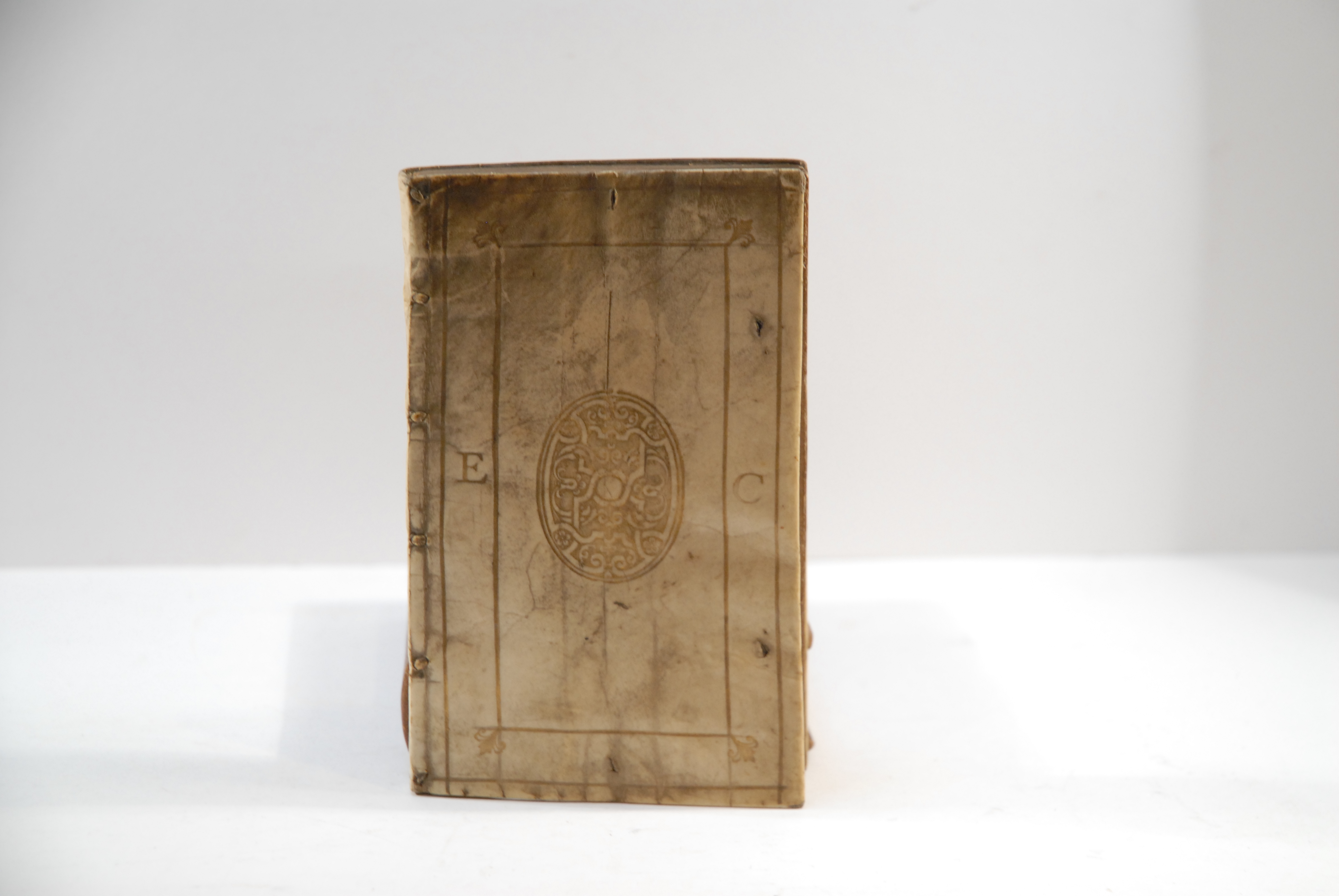

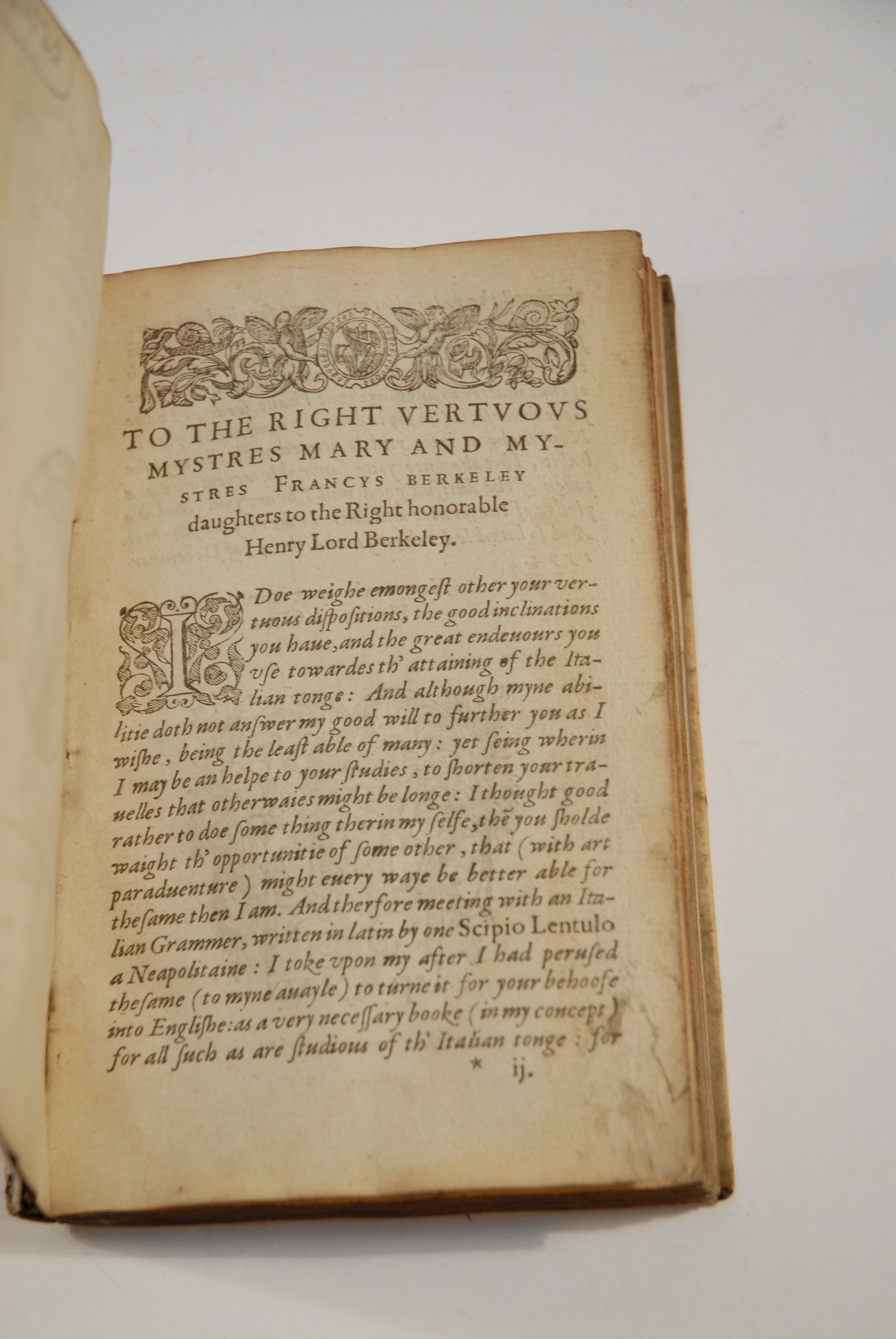

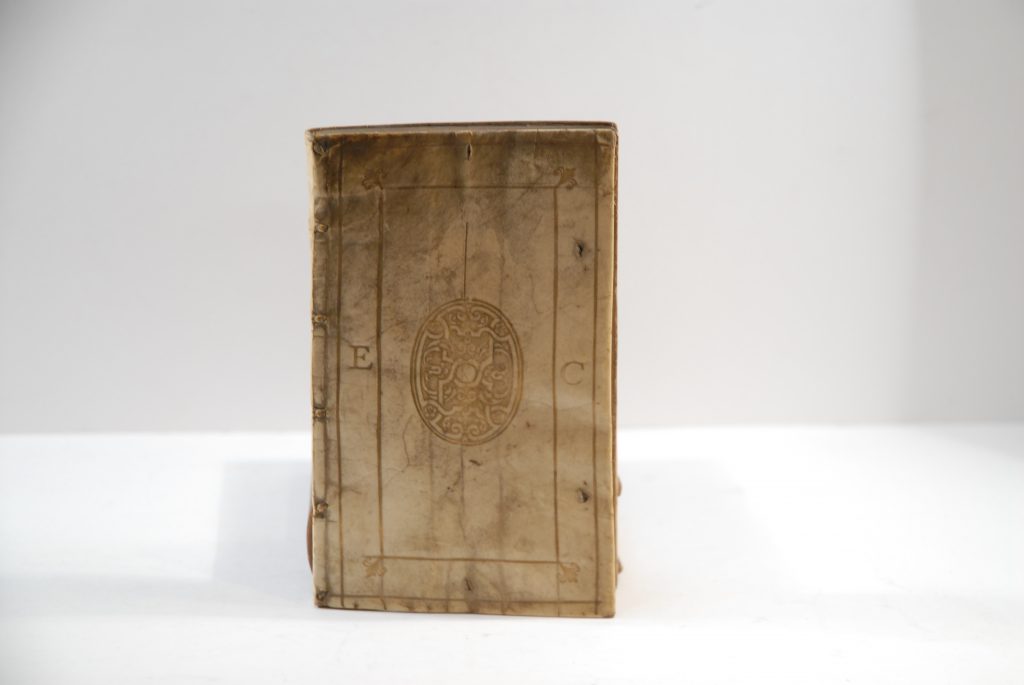

FIRST EDITION thus. 8vo. pp. [iv] 155 [i]. *², A-I , K L². Roman and Italic letter. Vautroullier’s woodcut anchor device on title, floriated woodcut initials, grotesque headpieces, large woodcut grotesque tailpieces with Vautroullier’s initials T. V, monogram in contemporary hand at head of title-page, bookplate of Alan Lubbock on pastedown, letter, loosely inserted, from W. O. Hassel at the Bodleian Library, concerning provenance. T-p and next leaf a little soiled, light age yellowing, faint water-stain to outer margin of a few leaves, rare marginal mark or spot. A very good copy, crisp and clean, in fine contemporary polished vellum, covers gilt ruled to a panel design fleurons gilt to corners of outer panel, large oval with strap-work design gilt stamped at centres, letters E and C, gilt stamped in each of the outer panels, spine double gilt ruled in compartments, fleurons gilt at centres, remains of four ties, a.e.g. covers a little soiled.

Very rare, beautifully printed, first edition of the translation into English of this Italian grammar, from the library of Sir Edward Coke, finely bound with his monogram on the covers. The work is a translation of Lentulo’s ‘Italicae grammatices praecepta’ by Henry Grantham, a popular Italian grammar, republished in 1587. “One other Grammar was issued in England just prior to the publication of [Florio’s] ‘Firste Fruits’, a translation of Scipione Lentulo’s ‘Italicae gramatices praecepta ac ratio’ by Henry Grantham (who in 1567 also published a translation of a fragment of Boccaccio’s Philocolo, ‘A pleasaunt disport of divers noble personages’), the original of which Migliorini notes was written specifically with foreigners in Italy in mind. An ‘Italian grammer’ appeared first in 1575 (reprinted in 1587) and provided a solid basis for the beginners acquisition of Italian, based as it was upon “the most servicable among the many [such] works then available in Italy … it is not only extremely clear, but completely unadorned, even more so than Thomas, for the most part schematic, with little commentary of exemplification, to the point that it often seems more a grammatical survey than a grammar”” Michael Wyatt. “The Italian Encounter with Tudor England: A Cultural Politics of Translation.”

Hassel catalogued 1,237 items from the library of Sir Edward Coke, which reveal the great variety of his reading; apart from the expected yearbooks, Reports and Registers of Writs, there are such diverse items as Diodorus Siculus and Dante, a Welsh grammar and works on Husbandry. Hassel states in his letter inserted with this copy “This would be one of the very few Italian books included in Sir Edward’s collection in its original binding which does not contain marks of having been derived from Sir Christopher Hatton. Hardly any of the Italian books have Coke’s autograph or binding: and nearly all the Italian books (when this evidence has not been destroyed by 18th century rebinding) have either the binding or autograph of Christopher Hatton. “Hailed by Sir Robert Phelips as ‘that great monarcha juris’, and by Richard Cresheld as ‘that honourable gentleman to whom the professors of the law, both in this and all succeeding ages are and will be much bound’, Sir Edward Coke was the finest lawyer of his generation. Sir Roger Wilbraham thought his legal talents were ‘above all of memory’, while Sir Julius Caesar ranked him as ‘one of the greatest learned men amongst the common lawyers of England’. Even James I, who grew to detest him, acknowledged Coke as ‘the father of the laws’. Much of Coke’s legal skill relied upon a sharp intellect and a prodigious capacity for work ..but it was also the product of immense learning. Coke collected a huge library of books and manuscripts, and by his death he owned around 1,200 volumes, considerably more than most college libraries of the period. Naturally many were law books, but the largest part of the collection was concerned with historical matters. Although not a member of the Elizabethan Society of Antiquaries, Coke regarded it as essential to study the past in order to comprehend England’s laws and constitution. He applauded Edward I as ‘our Justinian, the wisest prince that ever … [was] till our king’, and was almost as much in awe of Edward III, whose reign he regarded as the golden age of Common-Law pleading. Through historical study, Coke concluded that ultimate sovereignty lay with the Common Law. Not merely was this superior to Civil or Canon Law, but both Parliament and the king were subject to its authority. In an era when the Crown increasingly operated outside the strict parameters of the Common Law, this was a dangerous view to hold.” Andrew Thrush and John P. Ferris “The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1604-1629.”

A beautiful copy of this rare work with exceptional provenance.

In stock