RESERVED

THE FIRST ENCYCLOPEDIA

Etymologiae

England, second half of thirteenth century.£95,000.00

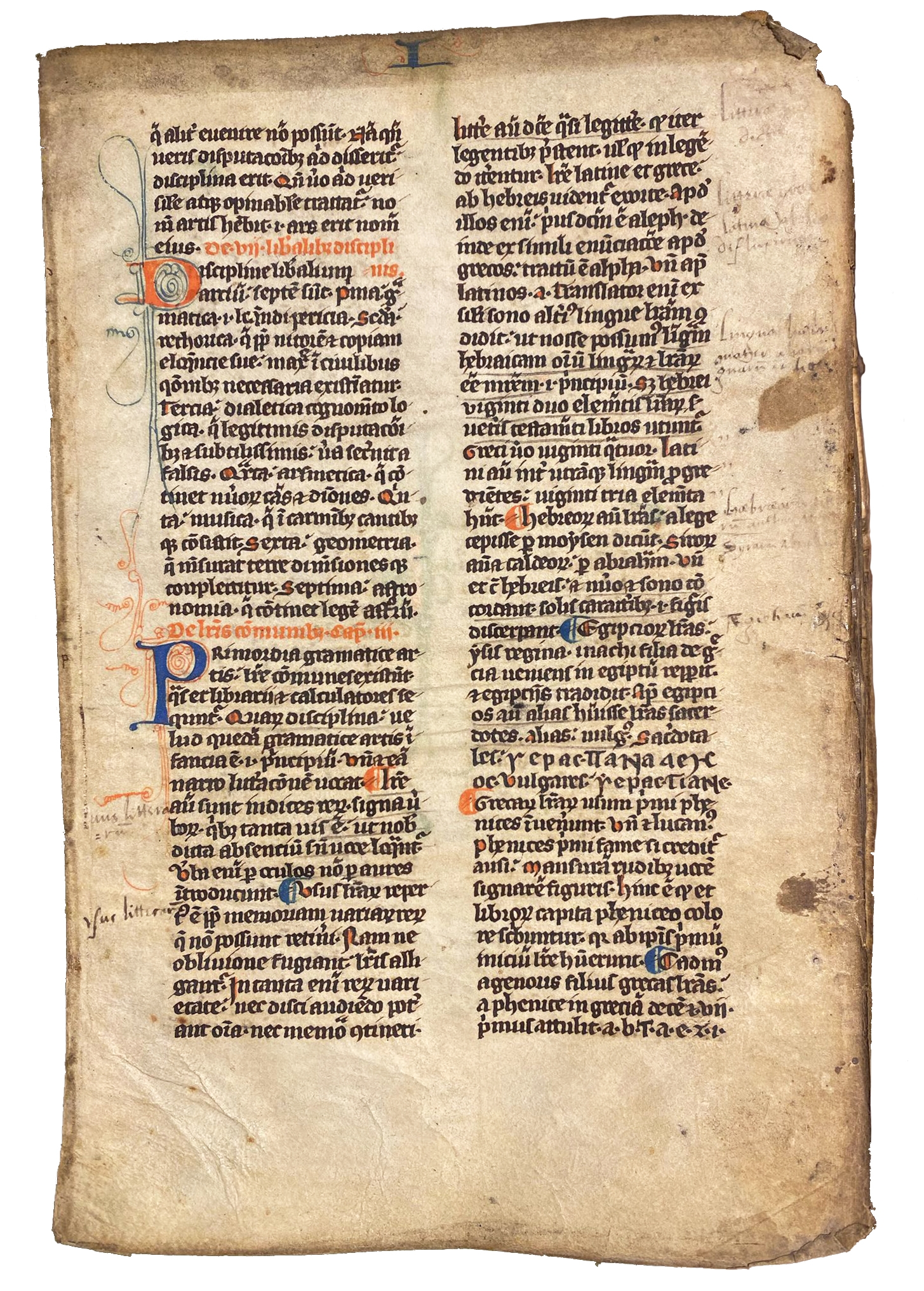

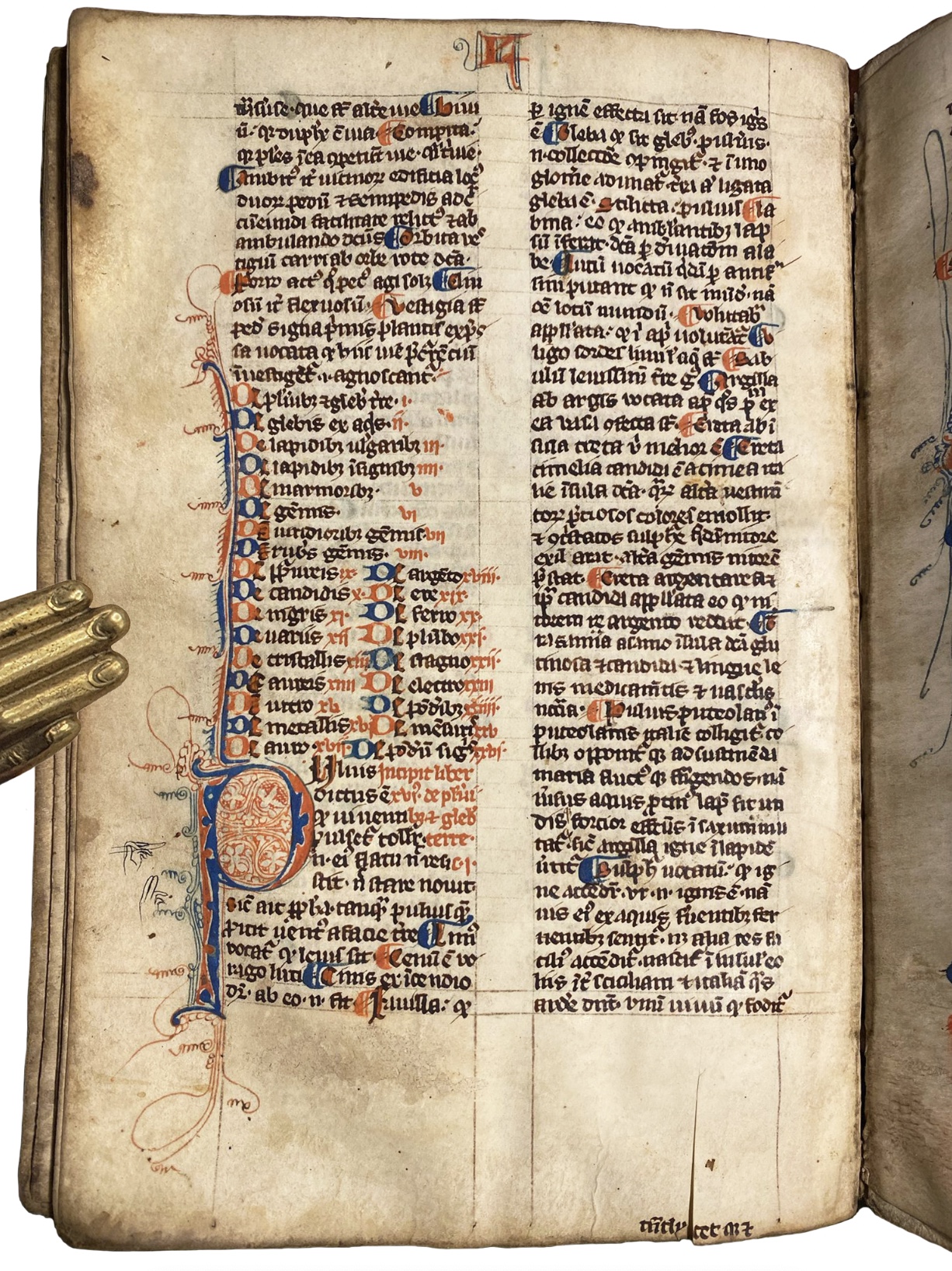

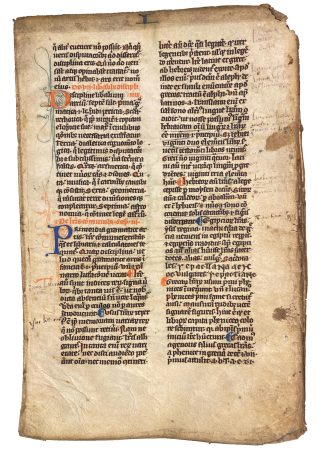

Large 8vo, 208 by 134mm., 188 leaves (plus strip from another loosely inserted; no endleaves, medieval pastedown at back), wanting all leaves from first quire except a single leaf (I:1 ending-opening I:4), and some from end (text here ends in XX:8, so eight chapters short), collation: i1, i-v12, vi11 wants a single leaf, vii9 wants 3 leaves, one a loose strip in the volume), viii-xv12, xvi11 (wants least leaf). Double column, 40 lines of good English university script, numerous abbreviations, capitals touched in red, red rubrics, small initials (including running titles) in red or blue with contrasting penwork, larger ones in both colours and often with blank vellum foliage left in middle by penwork in characteristically English style, capitula lists with blue and red spiky foliage filling margins and on occasion a penwork king’s head or drollery creatures, fol. 27r with seven diagrams in red showing phases of the moon, two leaves with 17 simple diagrams of geometric shapes in red penwork, book 16 opening with two apparently medieval sketches for drawings of hands in the margin, another lower margin in same book used for a drypoint sketch of someone kneeling before a female figure (perhaps the Virgin or saint), a few leaves split, two others with corners fallen away (one with later repair loose in volume), some cockling throughout, small ink spots and light marginal stains, light first leaf of quire two much discoloured showing that most of first quire lost for some time and last surviving leaf from that perhaps surviving tucked into the volume, slightly trimmed during last rebinding, but overall very presentable. Medieval binding, partly disbound with front board lost, but most quires attached to structures, back board medieval wood attached by 5 thongs, once covered in leather (now gone), channel from clasp once at midpoint of back board, ends of nails from two apparent strap-attachments once mounted on backboard, binding structures somewhat battered. In folding box.

Provenance:

- Made to be a fine and handsome volume, almost certainly prepared for use in a monastic or cathedral library, with marginal annotations in medieval English hands demonstrating its use up to the sixteenth century at least. The most common hand among these is sixteenth century and writes in Greek as well as Latin (see fol. 19r for an example).

- It would have entered private ownership at the Reformation, and was used for scribal practise and sums on four occasions by an eighteenth-century English hand. Among the scrawls on the back pastedown the name ‘Leathersons’ appears.

- Recently coming to light in an American private collection.

Text:

No other encyclopedic text in the Western world has had anything like the impact of that written by Isidore of Seville (c. 560-636). Its author was one of the last humanist polymaths of antiquity and one of early Christianity’s most influential scholars. He was part of the intellectual renaissance in the seventh-century Visigothic court, and was notably close to King Sigebut (c. 565-620/1), to whom the first version of this work was dedicated. It has been suggested that he composed it as a form of summa for his recently-civilised barbarian masters, but it quickly found other readers in mainland Europe and became the most widely consulted scientific reference work of the Middle Ages. It survives today in nearly a thousand manuscripts (Barney et al., Etymologies of Isidore of Seville, 2006, p. 24). The present codex distinguishes itself within that group as a fine English codex of the text.

The text itself encompasses such diverse topics as grammar (book I), rhetoric (II), mathematics (III, including music and astronomy), medicine (IIII), law (IV), the Bible (with sections on writing materials and libraries, specifically the use of papyrus for the earliest copies of the Bible, and the invention of parchment in the city of Pergamon, hence its name), the Church and celestial beings (VI-VIII), the languages of men and the alphabet (IX-X), humans (XI; including the functioning of their body parts), animals, fish and birds (XII), the elements (XIII), earth and heaven (XIV), cities and rural life (XV), stones, metals and gems (XVI), agriculture (XVII), war and games (XVIII-XIX, with sections on arms, the circus, wrestling, dramatic and orchestral performances, gladiators and dice and ballgames), and finally food and drink (XX). Isidore culled vast amounts of information from the ancient authors available to him, but sadly many not to us, thus preserving much material since lost.

The central thesis of the work remains at the heart of modern science, as the grandest medieval product of what we would now call a database. On a number of occasions Isidore repeats information from his sources verbatim, indicating that to organise the thousands of fragments of information into chapters, he invented a filing system similar to a card-catalogue, using slips of parchment which he called schedae: “A scheda is a thing still being emended, and not yet redacted into books” (VI.xiv.8). In recognition of this in 2006, Pope John Paul II proposed that Isidore be recognised as the patron saint of the Internet and computer users.

“Isidore thus became the chief authority of the Middle Ages and the presence of his book in every monastic, cathedral, and college library was a main factor in perpetuating the state of knowledge and the modes of thought of the late Roman world” Printing and the Mind of Man p. 6 on the printed edition of 1472.