GIEGHER, Mattia

Li tre trattati

Padua, Paolo Frambotto, 1639£12,500.00

Oblong 4to, three parts in one, pp. (xx) including portrait of author, 54 (xxxiv), + 48 engraved plates (two folding), two ll. misplaced. Roman and italic letter, woodcut floriated initials, typographical ornaments, full page engraved portrait of author, 46 full-page engraved plates depicting napkins folded in artistic ways, different types of meat, poultry and fish, fruits and set tables, two fold-out plates illustrating carving knives and forks. Intermittent age yellowing, marginal fingersoiling to some outer margins, deckle edges. A very good, wide-margined copy, crisp and clean, in contemporary carta rustica, covers a little worn. Bookseller’s label ‘Chiesa – Milano”, bibliographic annotations and early manuscript initials “G.P.” (?) to front paste-down.

Second edition of this very rare and beautifully illustrated collection of three culinary treatises on table service and food carving by Giegher, including the very first work on the art of folding table linen. Complete copies, remarkably including Giegher’s portrait (often missing) are extremely rare.

‘Li tre trattati’ was a popular book: this second (posthumous) edition contains a new letter to the reader by the printer Frambotto, warning of a plagiarised version. Giegher’s plates have been reproduced and copied in many later cookbooks.

The Bavarian Mattia Giegher (born Mathias Jäger, c. 1589-1632) was a native of Moosburg who moved to Padua at the age of 22. Here, he worked as a ‘trinciante’ (meat carver) and ‘scalco’ (banquet manager), organising banquets and waiting tables for the prestigious German community of jurists at the University of Padua. At the time, aristocratic banquets were of enormous cultural importance, organised by courts and as a way of displaying wealth and power, consolidating friendships and forming political alliances. ‘Li tre trattati’, first published in 1629, is a fascinating manual by Giegher containing all the information required for preparing and serving food to high-class clients. It comprises the expanded versions of two earlier treatises – ‘Lo scalco’ (1623) and ‘Il trinciante’ (1621) – with the addition of a new and innovative work on napkin folding (never printed separately). At the time, fine dining was becoming more formal and elaborate in presentation: this work is an extraordinary witness of the unusual and extravagant dining practices of the rich and famous.

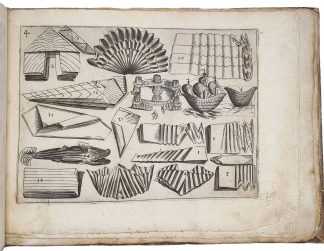

In his ‘Trattato delle piegature’ (Treatise on folding), Gieger for the first time describes in detail the art of napkin folding, using images for teaching and creative purposes. In addition to explaining how to fold napkins for wiping hands and mouth, he shows how to create complex artistic sculptures, called folded centrepieces. Renaissance table linens were expected to surprise and entertain: the plates in this treatise depict centrepieces shaped as birds, lions, fish, a crab, a tortoise, a dog, heraldic and mythological creatures, even a ship with four sails. These sculptures were not merely decorative, but objects with a symbolic meaning to be discussed by the participants. Interestingly, rather than providing models of certain shapes to be reproduced, Giegher teaches how to master the basic folding techniques (fan, curved and herringbone) so that the aspirant folder could invent his own designs.

The second treatise is dedicated to the profession of the ‘scalco’, sometimes translated as ‘head steward’ or ‘banquet manager’. The scalco was responsible for the organisation of every aspect of the banquet and for its success, from hiring the chefs and selecting what dishes to serve, to setting the tables. In this treatise, Giegher summarises the knowledge and skills that a scalco needs to possess: the first part explores the seasonality of foods indicating the best months of the year for eating certain meats, vegetables, fruits and mushrooms. Then, the author proposes long menus for meals that are perfect for different seasons or occasions: for example, the menu of a “breakfast of different fruits for noblewomen’, interestingly including a “pizza”, in this case being a particular type of cake. At the end, five plates show the proper placement of dishes on a table, and which foods they should contain.

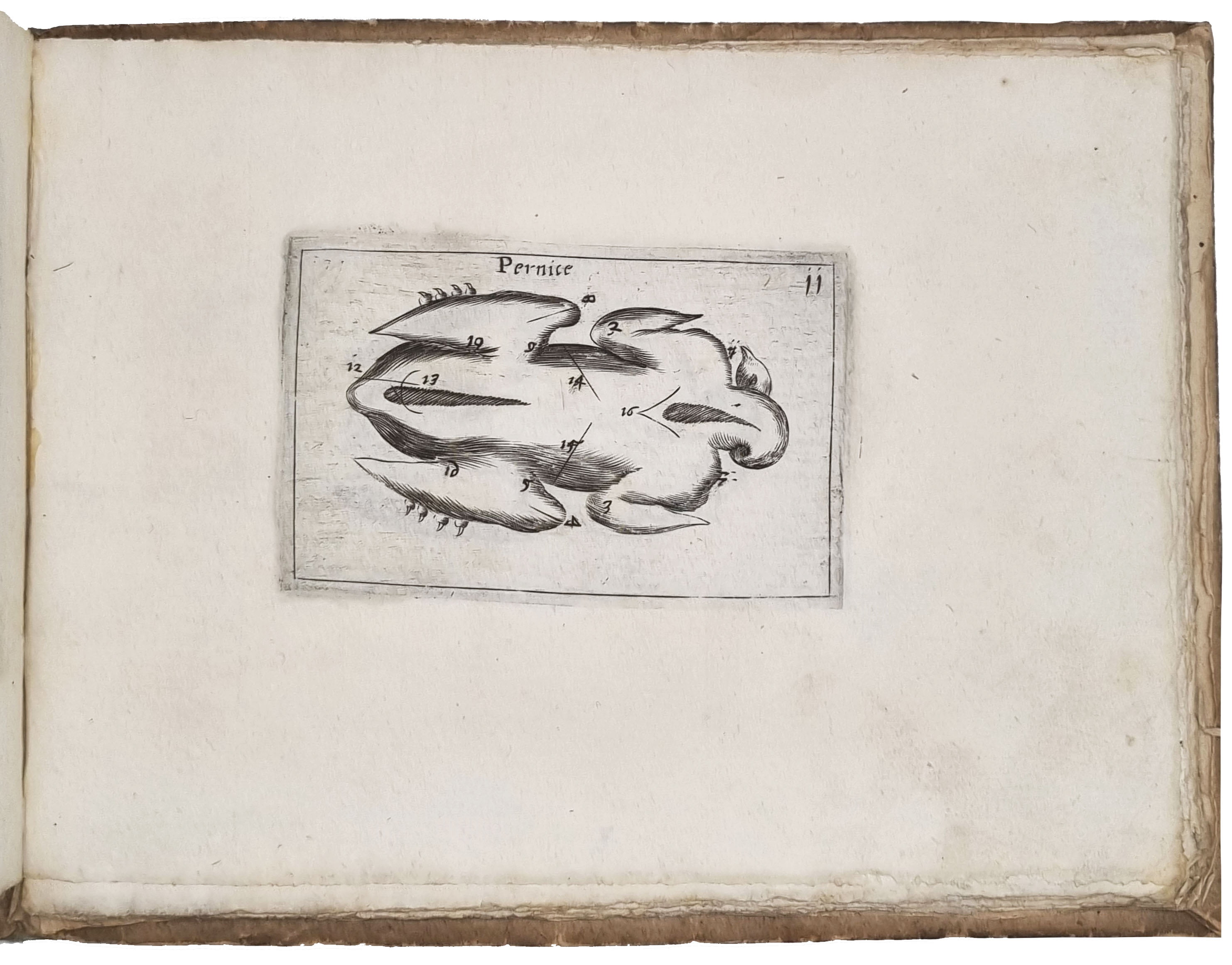

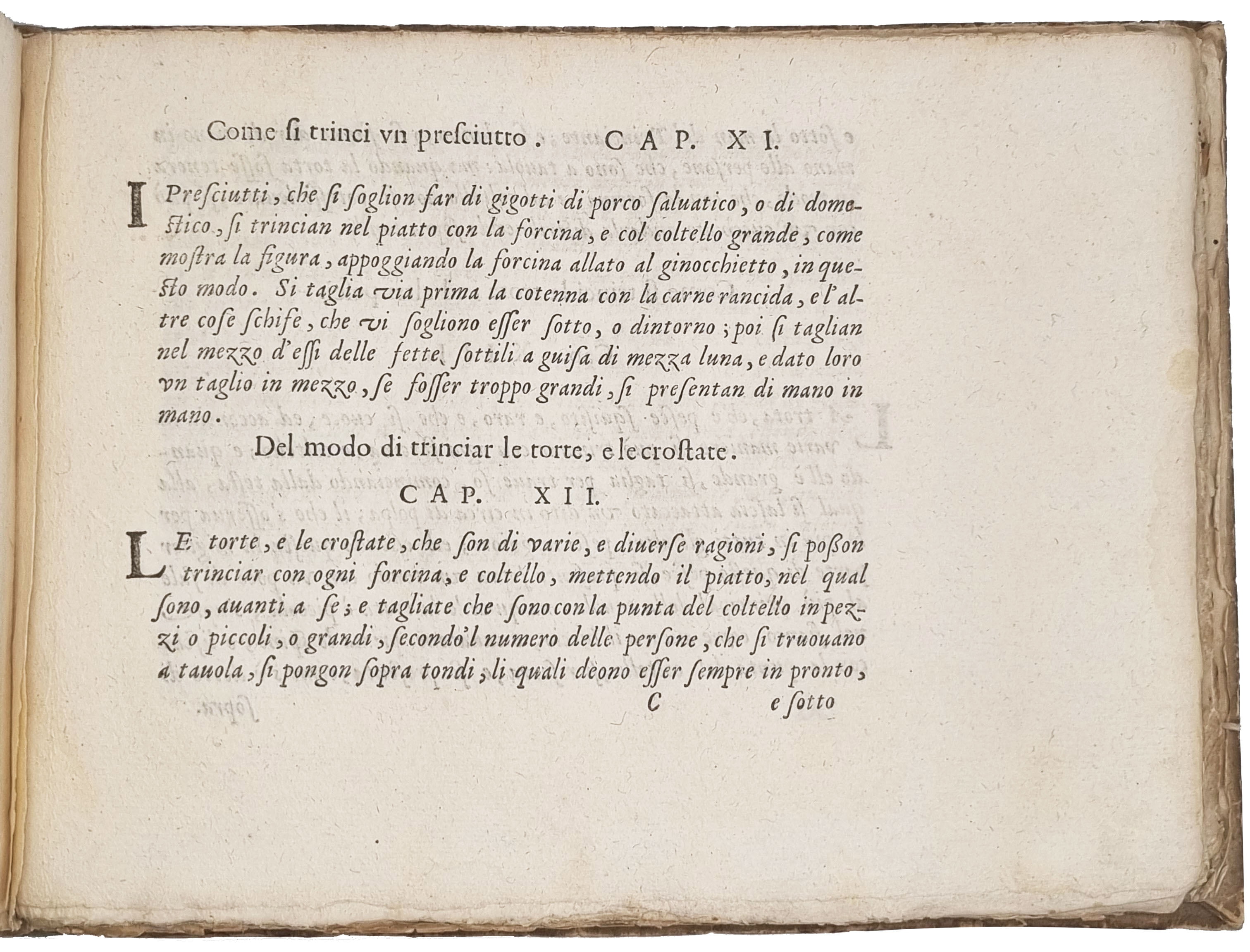

Finally, ‘Il trinciante’ (The meat carver) is a treatise on food carving and on the profession of the carver, “whose office is most honoured”. After listing the moral qualities of the perfect trinciante, Giegher delineates the correct posture and movements for carving (in order to avoid making mistakes and being laughed at), and then describes all sorts of poultry, fish, red meats, as well as fruit, cakes and pies – showing in numerous plates where and how to cut them: for example, carving a turkey requires 21 separate steps. Two charming plates illustrate decorative fruit peeling. As customary in treatises about professions, Giegher discusses his tools and how to clean and sharp them: two large fold-out plates depict an impressive array of knives, slicers and two-pronged forks (used to hold the meat steady).

USTC 4009695; Brunet II, p. 1588: “Curieux et assex rare”; Graesse III, p. 80; Vicaire p. 402: “Les trois traités de Giegher sont fort rares; on les trouve assez difficilement complets”, Bitting, p. 182. Not in BM STC It. 17th century, Notaker or Oberlè. Only three copies in the US (Morgan Library, Indiana University Library, New York Public Library).In stock