DE BOURGOGNE, Antoine

HANDSOME EMBLEMS

Mundi Lapis Lydius, sive Vanitas per Vertate falso accusata & convicta opera

Antwerp, typis viduae Jaon. Cnobbari, 1639£2,250.00

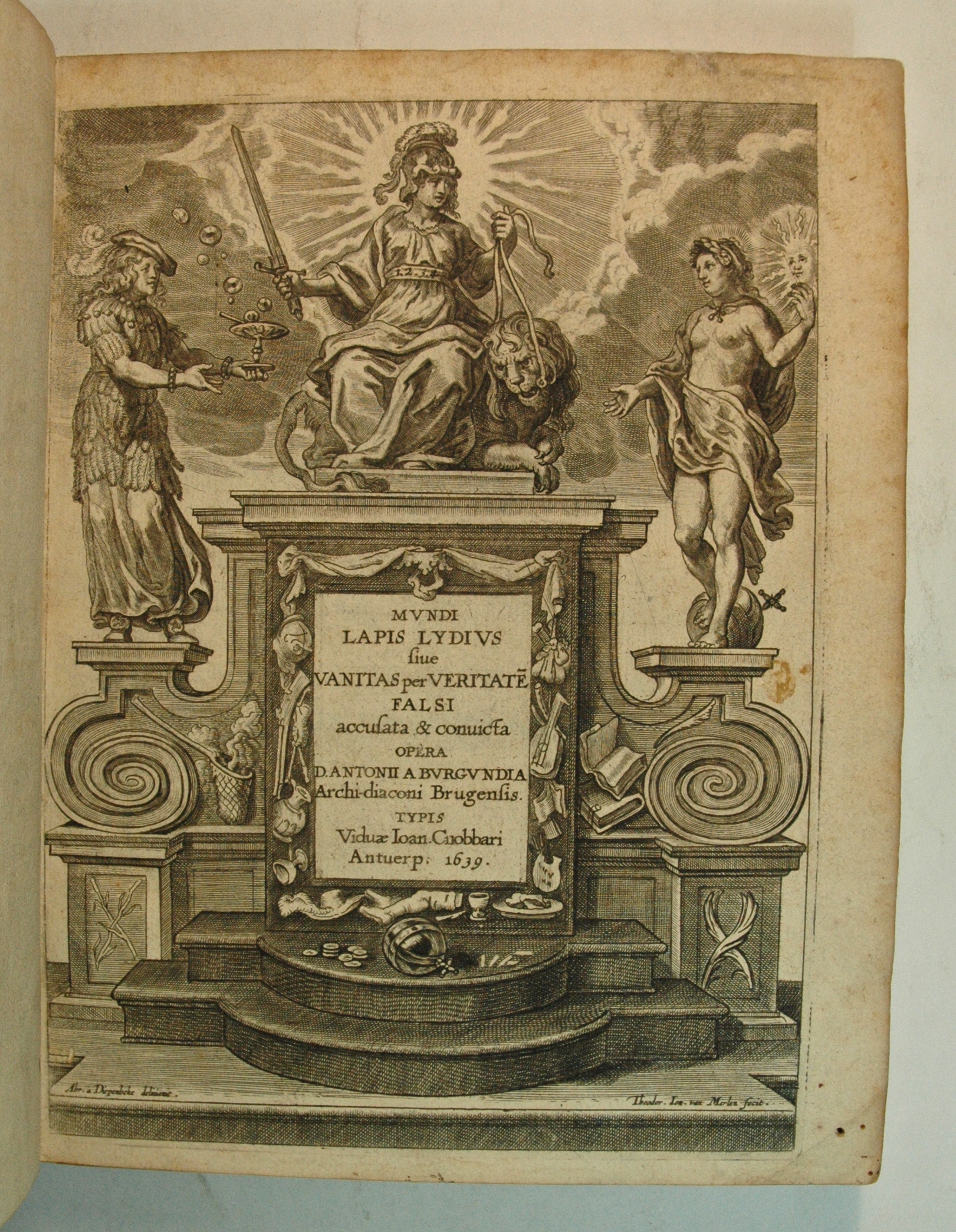

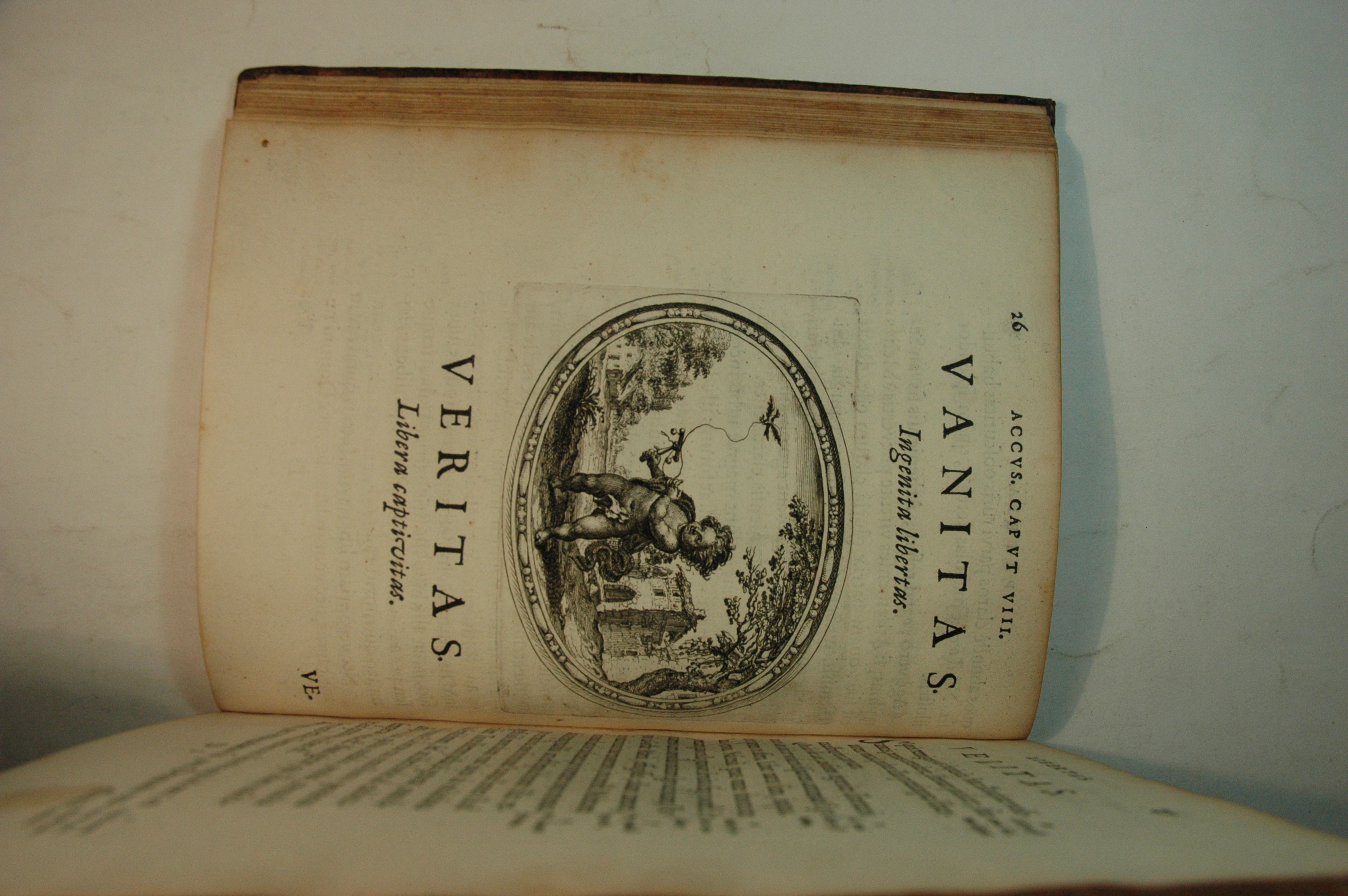

FIRST EDITION 4to. pp. [xxviii] 249 [xxvi]. Roman letter, a little italic, printed side notes, woodcut initials, head- and tail-pieces, engr. t.p. featuring three female allegories of Truth, Justice and Vanity by Theodor Johannes van Merlen after Abraham van Diepenbeeck, 50 engraved emblems by A. Pauli in strong and clear impressions, on p. 234 full moon rising over a river, hand-coloured. Light age yellowing, slightest worming to gutter and margin of t.p., couple of ll. slightly short at end of ream; a handsome and well-margined copy in contemp mottled calf with covers triple-bordered in gilt, spine gilt in six compartments with raised bands, very sympathetically restored.

An emblem book with a uncommon didactic twist: the typical pairing of each image with an instructive motto has been split in two, one describing the scene untruthfully (‘vanitas’), the other its reality (‘veritas’). For instance, surrounding an image of a printing house (p. 10) it is said that Verborum copia and Nihil copia, sed usus: although there is an abundance of words and writing, abundance means nothing without use. In fifty chapters, the book provides a dual commentary over subjects as diverse as memory, marriage, political power, fame, and eating habits. As de Bourgogne argues in the preface, the exercise proves that poor judgement sometimes allows vain conclusions to be drawn from truth. The work is critical of its own tradition, since other books of emblems encourage forming many different possible interpretations of word and image, both religious and profane. De Bourgogne’s recognizes both tendencies in the genre, and his commentary reveals to readers not only which he takes to be true, but instructs them how to arrive at truthfulness for themselves. The volume is a fresh and innovative continuation of his earlier emblem book, Linguae vitia et remedia (1631) which focuses on remedies for the abuse of language through insults, lies, blasphemies, and calumnies. It was popular into the 18th century, reaching several other editions and translation into Dutch and German.

Little is known about Antoine de Bourgogne (1594 – 1657), Canon and Archdeacon of Bruges, although in one of the five laudatory poems at the beginning of the Mundi Lapis, he is connected by his friend the poet Olivarius Vredius, with the ancient House of Burgundy, through his namesake Anthony, bastard of Burgundy to Anthony’s father Philip the Good (1396 – 1467), and finally Philip’s father John the Fearless (1371 – 1419).