[‘Book of secrets’].

MEDICINE & CRYPTOGRAPHY

[‘Book of secrets’].

Manuscript on paper, France, last quarter of the 17th century.£3,250.00

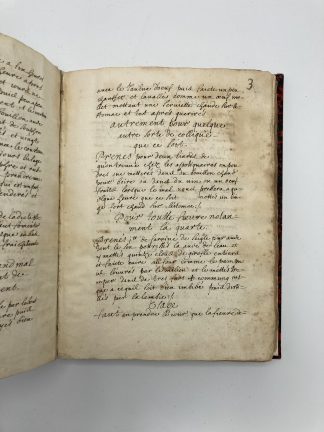

4to. ff. [1] + [78]. Manuscript on paper, black-brown ink, in French, two cursive hands, one on first leaf only, indecipherable watermark. Slight browning, light water stain to upper outer corner of first gathering, minor marginal foxing, small tears along gutter of fol.4. A very good copy in C20 half vellum over marbled boards, armorial dry-stamp with rampant lion holding sword to one leaf.

An interesting anonymous ms ‘book of secrets’ in French, with recipes for the preparation of a variety of substances, from medical remedies to varnish for paintings, and even an unpublished short treatise on French cryptography (‘dechiffrer’). It was likely the personal reference book of an apothecary or physician, and the material appears to be unpublished. The ms begins with medical remedies, e.g., against asthma, with herb infusions, and continues with a variety of conditions such as colic, syphilis or pox, epilepsy (called ‘mal de saint Jean’), fevers, dysentery, vomiting, deafness, ‘esquilencie’ (tonsil abscess), gout, ‘mal de ratte marveille’ (leptospirosis), venereal illnesses, scorbutum, etc. A few sections are devoted to women’s illnesses, such as the various conditions of breasts, beginning with long recipes – the longest in the ms – which employ alkermes, rhubarb, saffron, gum arabic and ‘snake’s tongue’ (a type of plant); or the delivery of still-born babies. Most medicaments are made from simples or mineral ingredients such as mercury and antimony, though some have peculiar names like ‘Manus Dei’, apparently going back to Avicenna but used more frequently in the early C18. Among the sources named are ‘the apothecary of Pierre Chaset’; Paracelsus, mentioned in passing; Theodore de Mayerne, physician of King James I and Prince Henry; Monsieur des Bouchetieres from Poitiers; Dardaine Jacobin, friar in Cologne; a Mons. de St Foelix; a Madame de Sequeville;

Fols 84-99 comprise a short treatise on French cryptography, for which we have traced no printed sources. In order to decipher texts, it suggests to start by identifying the letter ‘e’, the most frequent in French, most often preceded by ‘t’ in final position, while adverbs may be identified as they generally end with the same four letters (-ment). Thus, it teaches the reader to proceed by linguistic expectations and intuitions based on the fundamental lexical structures of French. Other sections deal with how to make sterile soil fertile, how to make trees produce more fruit, how to make honey clearer, and how to make ink and pigments, or how to make varnish to paint on wood. ‘There was close and stable interaction between C18 academic chemists and certain groups of educated practitioners, especially apothecaries, assayers, mining officials, and, especially in France, commissioners of state manufacturers. […] Academically educated chemists performed chemical operations and gathered experiential knowledge at non-academic sites as well, such as pharmaceutical laboratories, laboratories for assaying, arsenals, and manufactories for dyestuffs, ceramics, and sugar; and a significant number of practitioners, especially apothecaries, were acknowledged as chemists’ (Klein, p.18). A most interesting manuscript.

U. Klein, Materials in Eighteenth-Century Science (2018).In stock

![[‘Book of secrets’].](https://sokol.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/IMG_5243-rotated.jpeg)

![[‘Book of secrets’]. - Image 2](https://sokol.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/IMG_5245-rotated.jpeg)

![[‘Book of secrets’]. - Image 3](https://sokol.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/IMG_5244-rotated.jpeg)

![[‘Book of secrets’]. - Image 4](https://sokol.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/IMG_5242-rotated.jpeg)