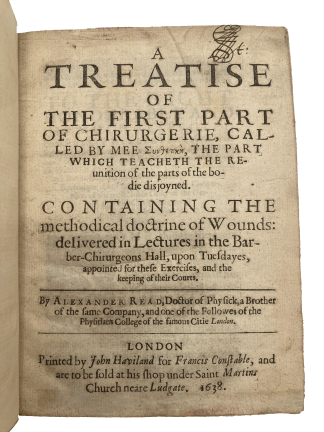

READ, Alexander.

ENGLISH PATHOLOGY, SURGERY, AND TREATMENT OF WOUNDS

A Treatise of the First Part of Chirurgerie.

London, Printed for John Haviland for Francis Constable, 1638.£5,250.00

FIRST EDITION. Small 4to. pp. [8], 247, [1]. Roman letter, little Italic. Decorated initials and ornaments. Very light browning, title a trifle dusty, gutter of gathering M imperceptibly strengthened. A very good, clean copy in contemporary English sprinkled calf, rebacked, double blind ruled, eps renewed, bookplate of the Fox Pointe Collection to front pastedown. Contemporary calligraphic monogram ST to title.

Fine copy of the first edition of this important, comprehensive English manual on the pathology, surgery, and treatment of wounds. Alexander Read (1598-1641) was an Oxford-trained physician who spent his career practising in England, and a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians. ‘Treatise’ was based on 33 lectures, covering as many chapters, delivered at the Barber-Surgeons Hall on Tuesdays in London – considering the textual and linguistic clarity of the text, Read must have been an excellent teacher. The work begins with an introduction on wounds, their description and different kinds, from basic procedures, such as stopping excessive blood flow, removing extraneous objects from wounds, or stitching, to more complex techniques, such as ‘the section of the hairy scalp and opening of the skull’ and ways to treat wounds in the abdomen, face, throat, and the ‘nervous parts’ (sinews and nerves). A few chapters are devoted to very specific ‘malignant’ wounds: made by a poisoned weapon (with a Paracelsian examination of the nature and physiology of poisons, and observations on whether the poison is still circumscribed to the wound or has already entered the system), the biting of a dog with rabies or of an adder, or by gun shot. For wounds of the head, Read states: ‘No wounds of the head although they seem small are to be slighted and neglected; for often times it falls out, that when a wound is received without fracture in the head, a man may die’, and ‘Wounds of the head often become more easy or hard to be cured by reason of the countries or climates’ (e.g., the ‘malign vapours’ that arise in Italy and the Mediterranean countries). A chapter is devoted to wounds in organs of the senses, such as the eyes, accompanied, as often, by Read’s own anecdotes: ‘An example of this I saw in Chester, in a young Gentleman, whose name was Fletcher; who in a duel being so wounded in the left eye, died about the fourteenth day after he received the wound.’ A beautifully-written, important medical manual, in very fresh and clean copy.

ESTC S115685; STC (2nd ed.), 20786; Wellcome I, 5356; Krivatsy 9430 (imperfect). Not in Osler or Heirs of Hippocrates.