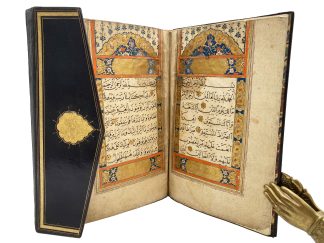

QUR’AN.

VERY INTERESTING COPY

QUR’AN.

Turkey., Manuscript on paper., Second to third quarter C17th.£59,000.00

4to, 222 x 150mm. ff. [540]. Manuscript on cream-coloured paper. Watermark: three interlaced crescents (Velkov-Andreev 119/1646), except for 10 ll., scattered throughout, with bird within a circle over three hillocks (approx. second half of the C17, cf. Briquet). Black ink, Ottoman naskh and riqa, two hands, rubricated waqf signs and tenth-verse markers, 11 lines per full page, verse-endings with roundels in gold, red and blue, all pages within blank and gold ruling, marginal prostration signs (probably slightly later) in blue, pink and gold with blue pen decorations. Traces of mistarah. First two leaves finely illuminated to a panel design, ruled in red and gold, upper panel with blue palmettes, and gilt dome with fleurons and tendrils over a blue background, panels above and below textblock with gold cartouche and fleurons over a blue background, side panels interlacing fleurons over gold and blue background. First leaf mounted, handful of old repairs at blank gutter of first gathering, small light stain (possibly old stamp) to text of first half dozen ll., not affecting reading, few ll. dusty, very light water stain to some upper blank margins of first half, very minor worming to some upper margins, repaired in places, small repair to one outer blank margin (waqf inscription removed), the odd marginal ms revision, occasional finger-mark to lower margin. A very good copy in probably C18 black goatskin, triple gilt ruled, gilt ropework to boards, gilt-stamped almond-shaped centrepiece and gilt palmettes above and below to boards, fore-edge flap with gilt calligraphic cartouche and Qur’an aīah, minor repairs to folds, marbled eps, endleaves with three moons and PB watermark. Colophon ‘katabuhu hasan uskudāri ghafara dhunubahu āmīn sanah 1013H [1604/5AD]’.

An exquisitely decorated ms Qur’an produced in the second to third quarter of the C17, likely in Istanbul. The initial charming illumination, as well as the decorated prostration signs, are reminiscent of floral designs used in Istanbul, at the Imperial Palace school: e.g., by an unknown illuminator of Suleyman Efendi Üsküdârî (Derman, ‘Ninety-Nine’, n.32, 1673), and by Hâfiz Osman’s (1642-98) illuminators Kubur Hasan Çelebi (Derman, ‘Ninety-Nine’, n.39, 1682) and Hasan bin Mustafa (Derman, ‘Letters of Gold’, n.15, 1682, and n.16, 1684).

‘Before printing […], [in Ottoman Turkey] there existed a class of scribes who earned their living by making copies of the Qur’an […]. People relied on manuscripts [for personal devotion], acquiring copies by illustrious calligraphers or minor scribes, depending on their means’ (Derman, ‘Ninety-Nine’, p.16). Especially under Mehmed IV (1648-87), many of the great calligraphers worked for the Imperial administration, with ‘the important manuscripts kept there [being] used as models by calligraphers’ (Bayani, p.80), and they trained dozens of pupils who continued the tradition. Our anonymous scribe may not have been a native speaker of Arabic, and was likely a student of calligraphy or a non-professional calligrapher working in the Imperial administration, as shown by the odd incorrect letter (e.g., an initial letter written in the medial form after an ‘alif’), the handful of incorrect surah titles where the text begins with identical or similar wording (e.g., surat ash-shu’ara titled surat al-qasas), and space forgotten for the verse marker in the third line of surat al-baqara. The 10 randomly supplied leaves, attached to the stub of the original ones, were likely rewritten to revise mistakes in the sacred text – indeed, ‘if a mistake was found that could not be corrected, the page would be removed and replaced. Such removed pages are called “muhrec sahife”’ (Derman, ‘Ninety-Nine’, p.17). Two pages display a more expanded naskh, with more elongated letters, as if the scribe had decided to practice a different style, returning to the original, more compressed naskh soon afterwards. The theory that the scribe was an official using the imperial administration’s paper stock is also supported by the very rare watermark – three interlaced crescents or ‘sickles’ – which is European, recorded by Velkov-Andreev on an Ottoman document dated 1646.

The added colophon attributes this ms to the renowned scribe Hasan Üsküdârî (d.1614-15). Whoever our scribe may be, he was obviously influenced by the school of Üsküdârî – ‘responsible for the transmission of the definitive form of Ottoman naskh’ (Bayani, p.66). Üsküdârî taught Halid Erzurumi (d.1630-1) and Imam Mehmed Efendi (d.1642-3), who in turn trained all major Istanbul scribes active in the second half of the C17. Islamic mss, recorded as early as the C12, attribute copies to famous or earlier calligraphers – though ‘it cannot be ruled out that the authors of similar notes acted in good faith in a number of cases’ (Deroche, p.91).

A charming Qur’an, with interesting bibliographical features for the study of Islamicate manuscript production.

A. Velkov & S. Andreev, Filigranes dans les documents ottomans, I. Trois croissants, 1983; M. Bayani et al., The Decorated Word: Qur’ans of the 17th to 19th centuries (1999); B. Harun Küçük, ‘Arabic into Turkish in the Seventeenth Century’, Isis, 109 (2018), 320-25; M. Ugur Derman, Letters in Gold: Ottoman Calligraphy from the Sakıp Sabancı Collection, Istanbul (1998), and Ninety-nine Qur\\\' ān manuscripts from Istanbul (2010); F. Deroche, ‘Fakes and Islamic Manuscripts’, in Fakes and Forgeries of Written Artefacts, ed. C. Michel et al. (2020), pp.89-98. For Uskudari’s handwriting see .In stock