Pope Clement V.

RARE IN MANUSCRIPT

Constitutiones, with the Bull of Pope John XXII and Gloss of Johannes Andreae.

France (probably south, perhaps Avignon), mid-fourteenth century.£75,000.00

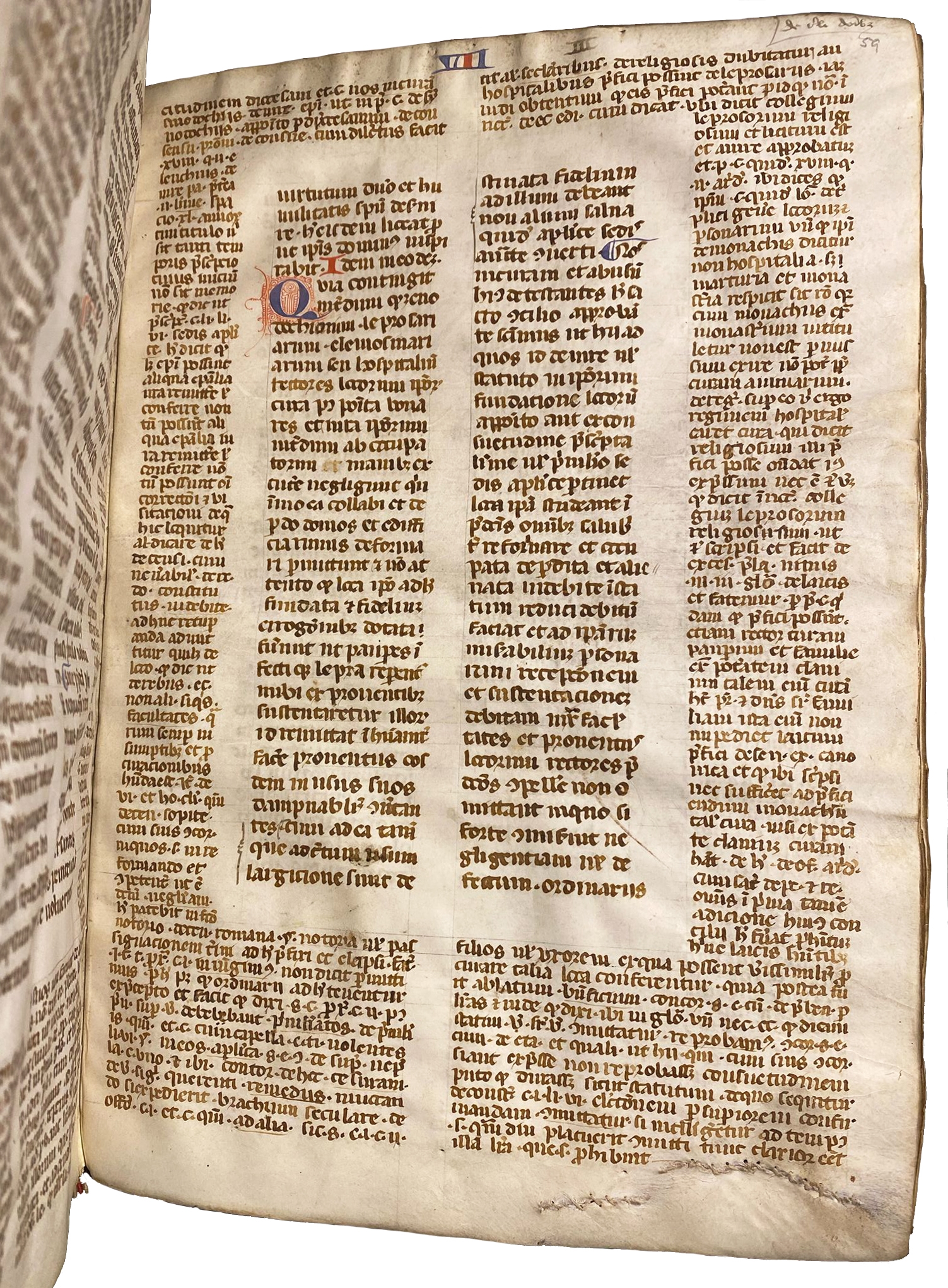

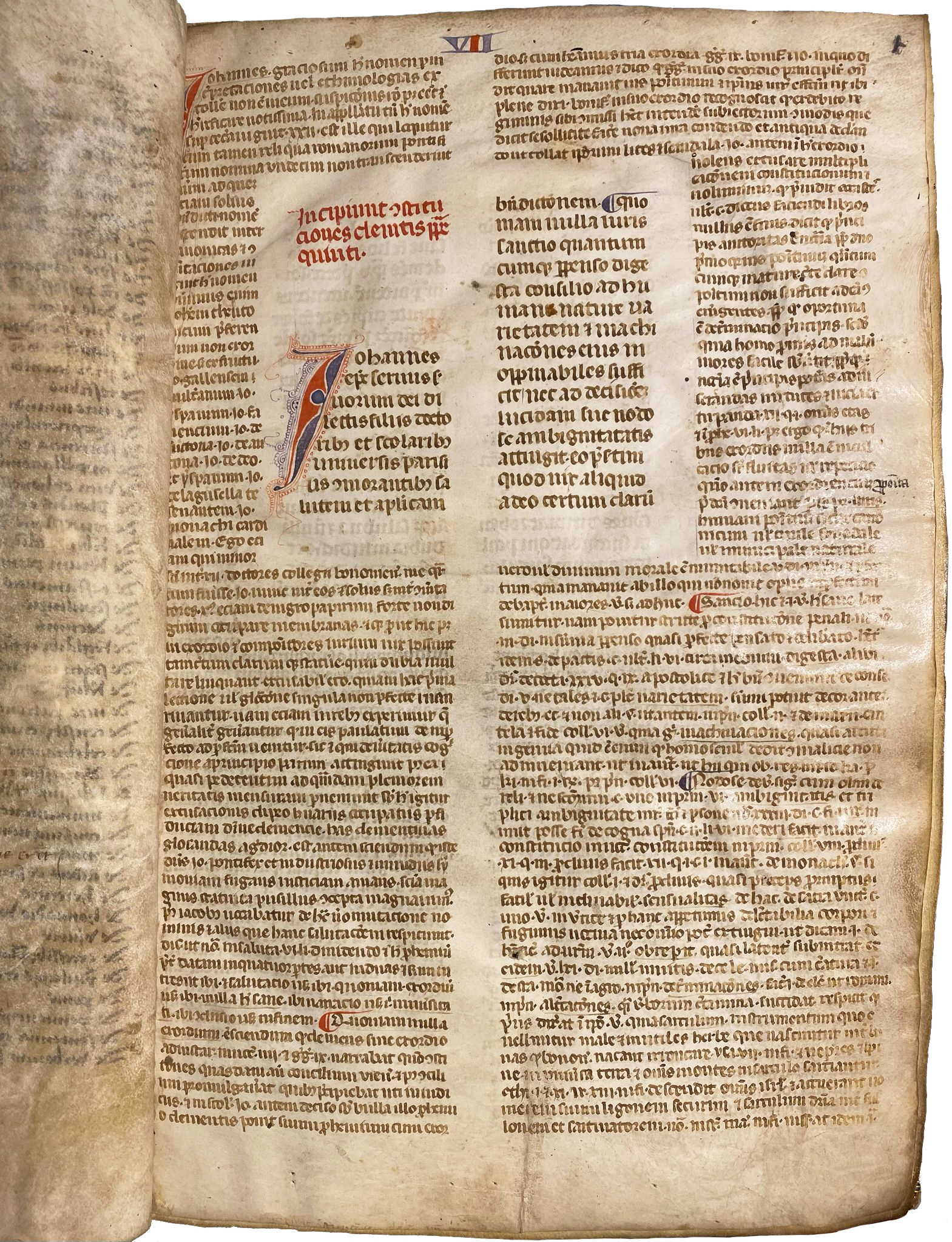

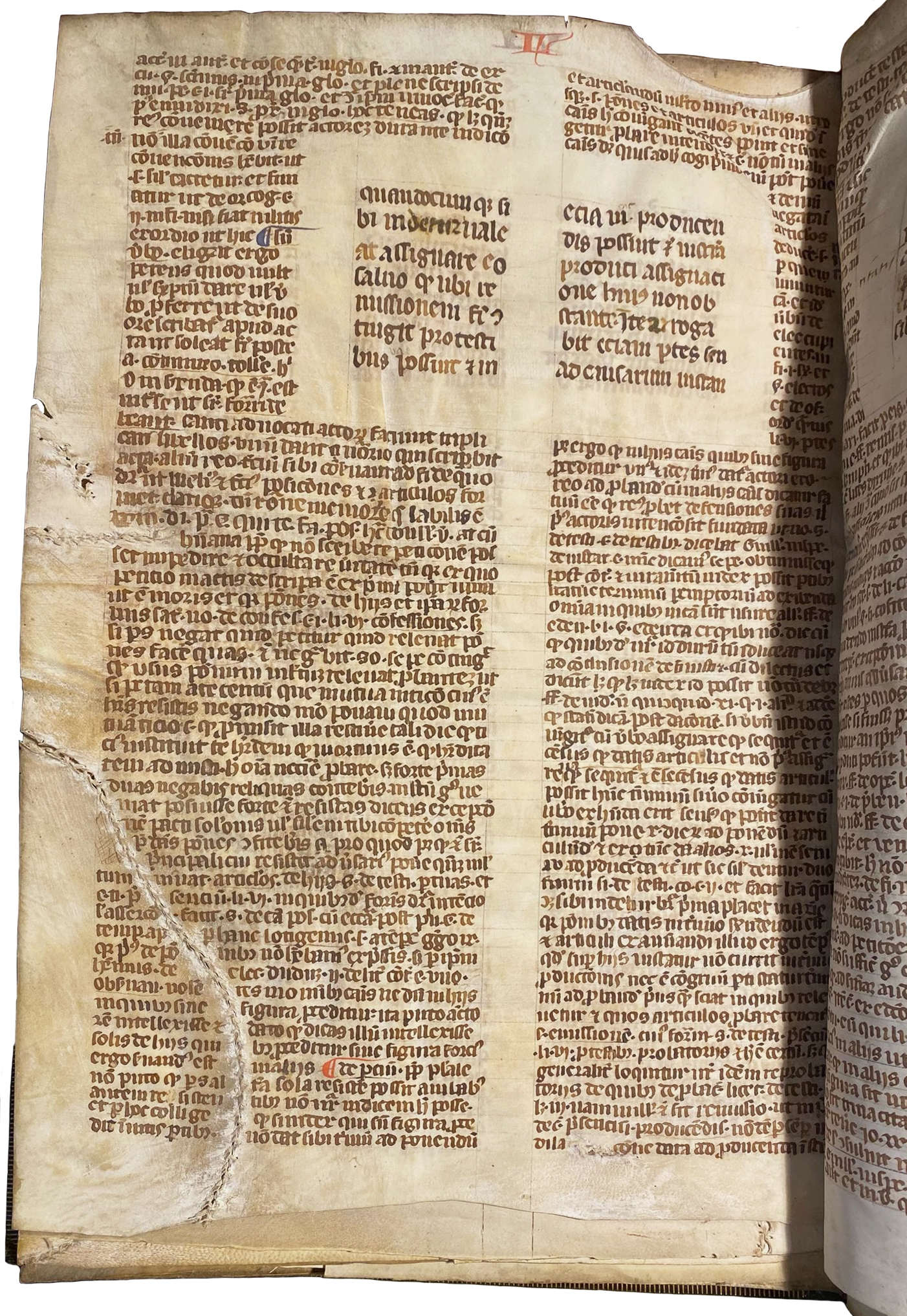

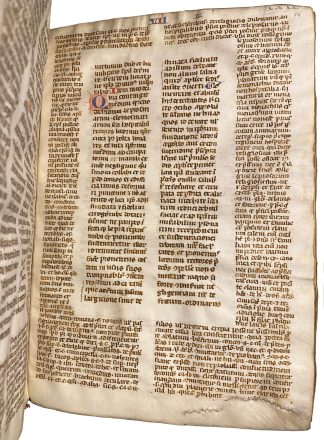

Folio, 310 by 210mm., 95 leaves (plus a contemporary endleaf at each end: that at front with a contents list), slightly erroneous foliation (skipping leaves after fols. 40 and 80), complete. Collation: i-viii12, catchwords throughout, two columns of main text of variable width (see below), with a very variable number of lines per page and, surrounded on outer sides by the gloss in smaller, more closely-spaced script with about 65 lines per column, the end of the gloss often written with short lines (see below). Running titles in red and blue capitals, two-line initials alternately blue and red with penwork in alternate colour, larger initials in both red and blue with penwork ornament in both colours, couple of ll. with substantial medieval repair to corner without loss, the odd minor spot or stain and slightly discoloured area of vellum, overall good condition; nineteenth-century morocco over pasteboards, framed with multiple gilt fillets of varying widths, spine with title gilt by Townsend & Son, Sheffield, stamped on front turn-in.

Provenance:

1. Most probably written and decorated in the decades immediately after 1326, when Johannes Andreae completed his Gloss. With script and decoration pointing towards France and Italy, this codex was likely produced in southern France, perhaps for study in Toulouse (compare the notably similar hand in a contemporary copy of the same work, now Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania, MS. 7, and probably made in Avignon for the bishop of Toulouse; and see below on identical layout). The references to the work of ‘Willielmus Mandagoti’ (f.10v, lower margin), i.e. Cardinal Guillaume de Mandagout (d. 1321), who wrote a treatise on the election of bishops and served as bishop of Aix-en-Provence and then Embrun lends support to this identification.

- By the sixteenth century the volume appears to have been in private hands in France, and a French hand of this date added the personal motto “Deum timenti bene erit” to its endleaves.

- William Bragge (1823-1884) of Birmingham and Sheffield, book collector, civil engineer, proficient linguist and traveller; most probably rebound for him; his sale at Sotheby’s, 8 June 1876, lot 152, to Quaritch: then their A general catalogue of books […]the supplement: 1875–1877(1877), no. 18,359.

- Henry White (1821/2-1900), FSA, with his armorial bookplate; Sir Sydney Cockerell adding to the front flyleaf that the manuscript was sold in White’s sale at Sotheby’s, 21 April 1902, lot 536, to ‘Ridler’.

- William Ridler (fl. 1877-1904), London bookseller of the Strand; on him see P. Kidd, Medieval Manuscripts from the collection of T. R. Buchanan in the Bodleian Library (Oxford, 2001), pp. xxii–xxiv.

- Bernard Quaritch Ltd again, c. 1930s: with their characteristic number ‘762’ written obliquely in a rectangle and price-code on the endleaves.

- Sotheby’s, 6 December 1993, lot 50, to Sam Fogg.

The Schøyen Collection of London and Oslo, their MS. 2160, recently de-accessioned.

Text:

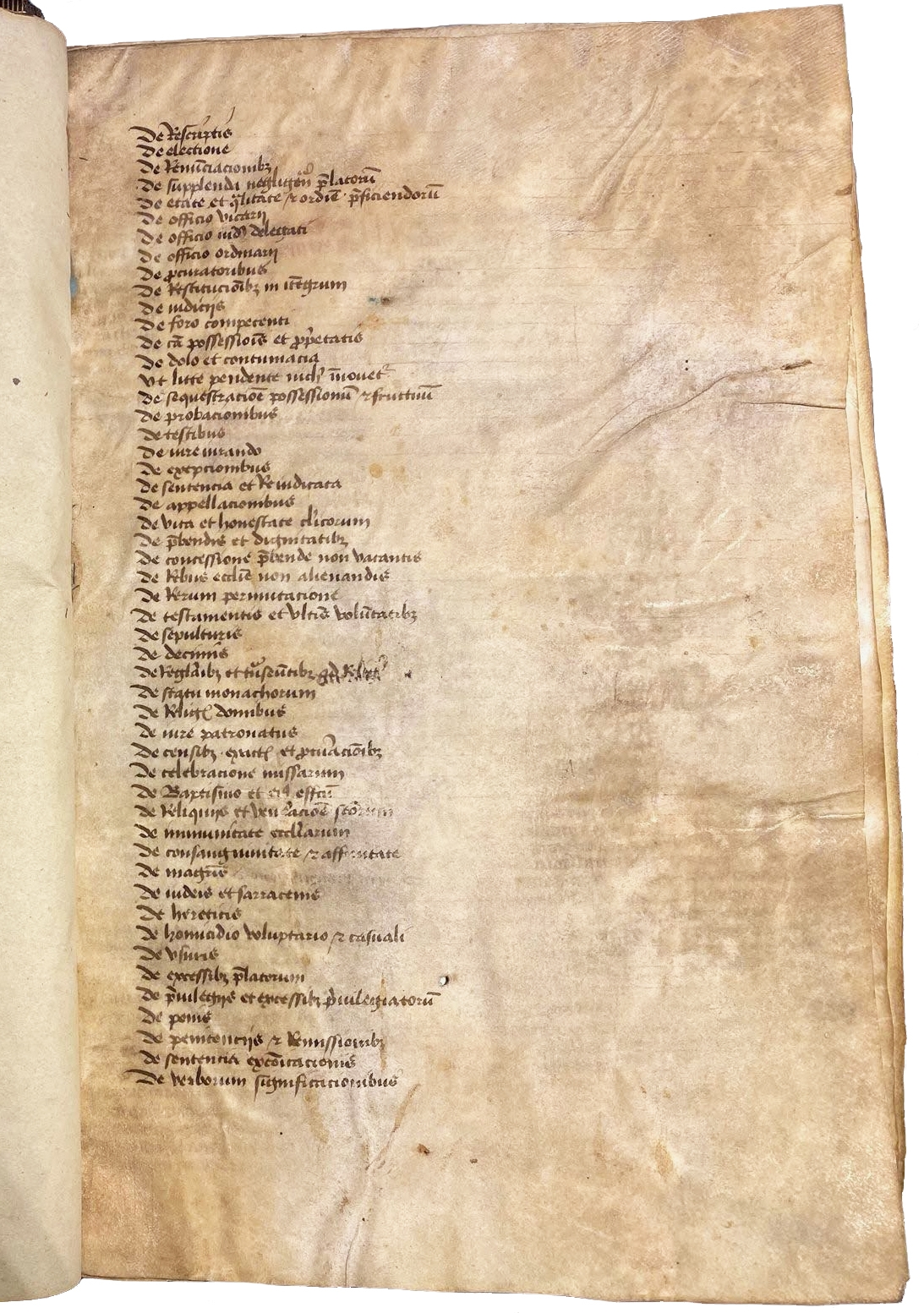

The text opens with a Bull addressed by Pope John XXII (1316-34) to the doctors and scholars of the University of Paris, used here as an introduction. The main text follows on fols. 2r-94v. With its arrival and boom of interest in university teaching, the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries saw the building of the fundamental textual building blocks of Canon Law as an academic subject. From the thirteenth century onwards the study of Canon Law was dominated by the Decretals of Pope Gregory IX, a series of explanatory glosses on the law arranged in five books. At the end of the thirteenth century, that was supplemented by the so-called Liber Sextus of Pope Boniface VIII, further clarifying their meaning and legal practice. Following this, in the early fourteenth century, Pope Clement V (1305-14) compiled the so-called Clementines intended to finish this task. These were promulgated less than a month before his death, and ratified by a Bull sent in 1317 to the universities of Bologna, Avignon, and Paris by Clement’s successor, Pope John XXII. These formed the seventh (and final) compilation of Canon Law and were unofficially known as the ‘Liber Septimus’ (hence the ‘L VII’ in the running headings and the ‘septimi libri’ of the final explicit). The gloss on the text by Johannes Andreae written c. 1322, came to be standard.

To this, a hand of the fifteenth century added a brief list of contents on the front endleaf.

Layout:

The mis-en-page here is at first confusing, with no two pages with the same number of lines, and each page laid out to perfectly accommodate the correct gloss and main text on a single side of vellum. In addition, where such arrangements meant that not enough gloss was available to completely fill the space around the main text, the blank marginal space forms gentley sloping triangles or arched indented areas, often with a single final line at the base of the section or page filling up the last line. This last feature has led others to suggest that this was done “so that the texts ends on the last line of the page”, presumably for ornamental affect, but this does not happen on every occasion. We can add that this was used to ensure that each major text division here ends in such a way, but there are further indentations of this form elsewhere as well.

Most other copies of the text in manuscript share some part of this labour-intensive layout, with the empty areas of margin usually rectangular and without the final long line, and that is the form that then made its way into early printings of the text. However, it is notable that the same form also appears in places in the Bryn Mawr manuscript noted above (see in particular fols. 15r, as well as 28r, 34r, 56v-57r), and this may well be a southern French feature, created for visual effect in the papal court’s time in Avignon (from 1309-76) or perhaps a quirk of texts written for the milieu of Toulouse University. A more wide ranging survey of the physical layout of manuscripts of the text from those centres and others is needed to understand this better.

This text is unusually rare in manuscript. We have located only four comparable examples in the US, Yale, Columbia, Pierpont Morgan and the Free Library of Philadelphia. The Harvard manuscript appears to lack Andreae’s commentary. For a work of such pre-eminent importance both in teaching common law and for practitioners, governing bodies and courts, as well as other institutions, it is remarkable that we know of so few comparable manuscripts. Even more oddly the Constitutiones are one of the most common legal incunabular texts, which suggests that manuscript versions did not just fail to survive up to modern times, but that they were not available, at least in sufficient numbers, even in the second half of the fifteenth-century.

Online at: https://openn.library.upenn.edu/Data/0003/html/BMC_MS07.html