MOLITOR, Ulricus.

ICONS OF WITCHCRAFT

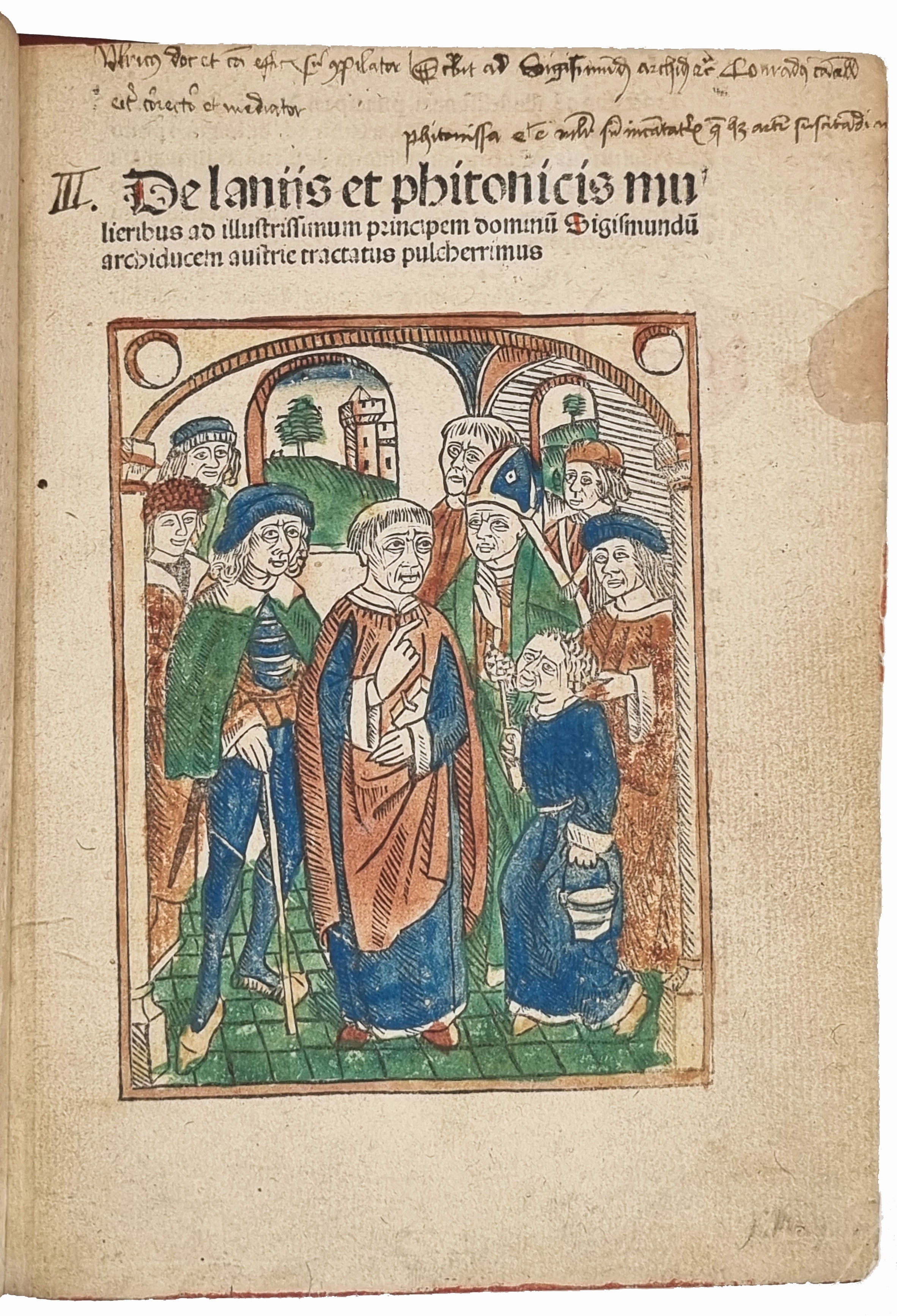

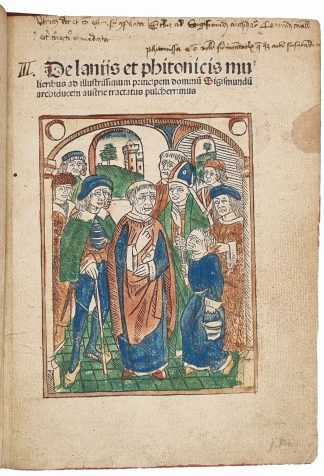

De laniis et phitonicis mulieribus.

[Cologne], [Kornelius von Zierikzee], [1497/99]£97,500.00

4to., 22 unnumbered ll. A-C⁴, D⁶. Gothic letter, 34 lines to full page, rubricated throughout. Seven to page woodcuts all in strong contemporary handcolouring, a three lines of contemporary Latin ms. at head of t-p, light early underlining, very occasional contemporary marginalia. Lower and outer margins a bit thumb and ink marked, the odd marginal splash or spot, a very good well margined copy on thick paper in soft crushed morocco C20th. Modern annotations to pastedowns and book label to fly, Menno Hertzberger’s pictural label to front pastedown.

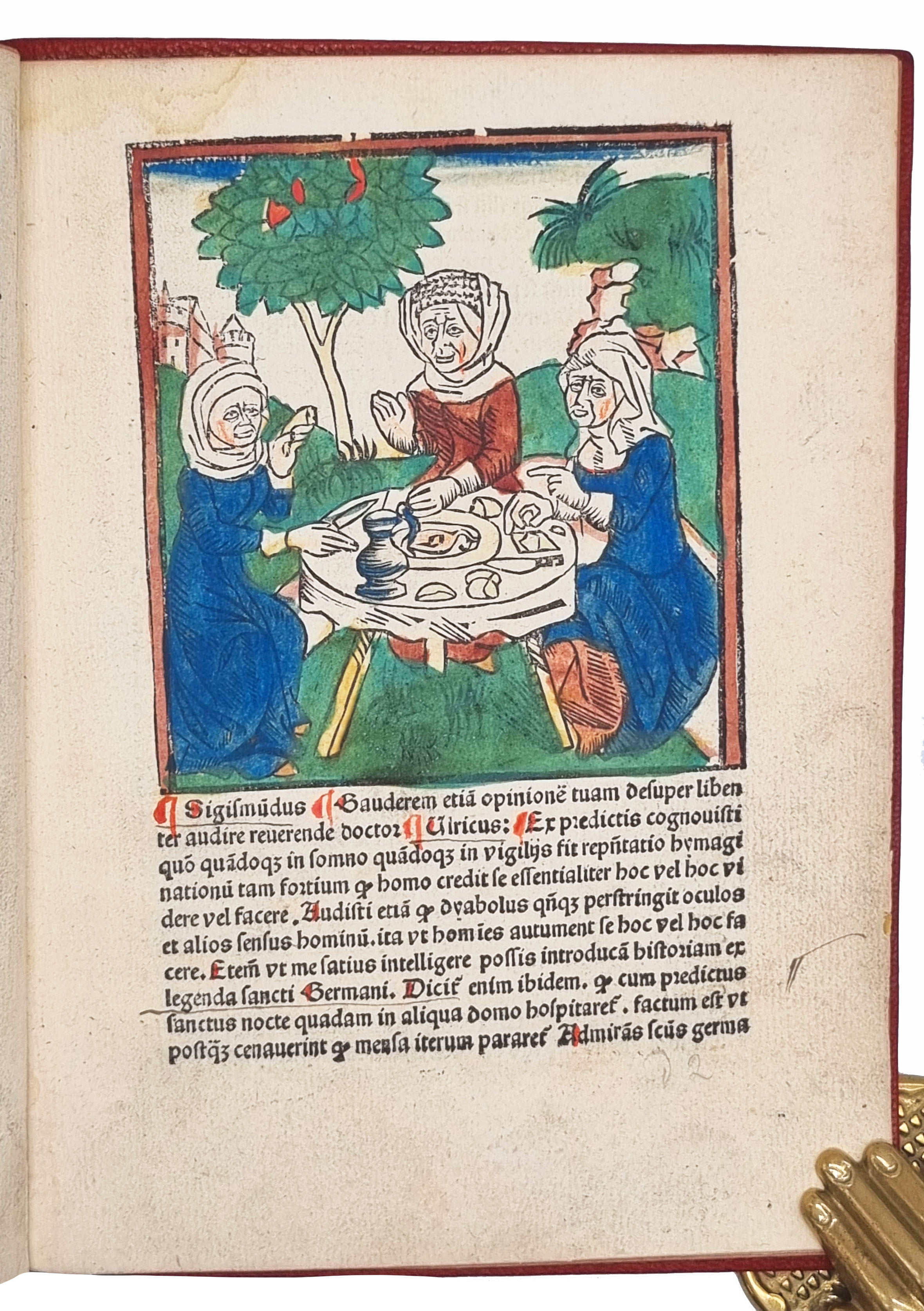

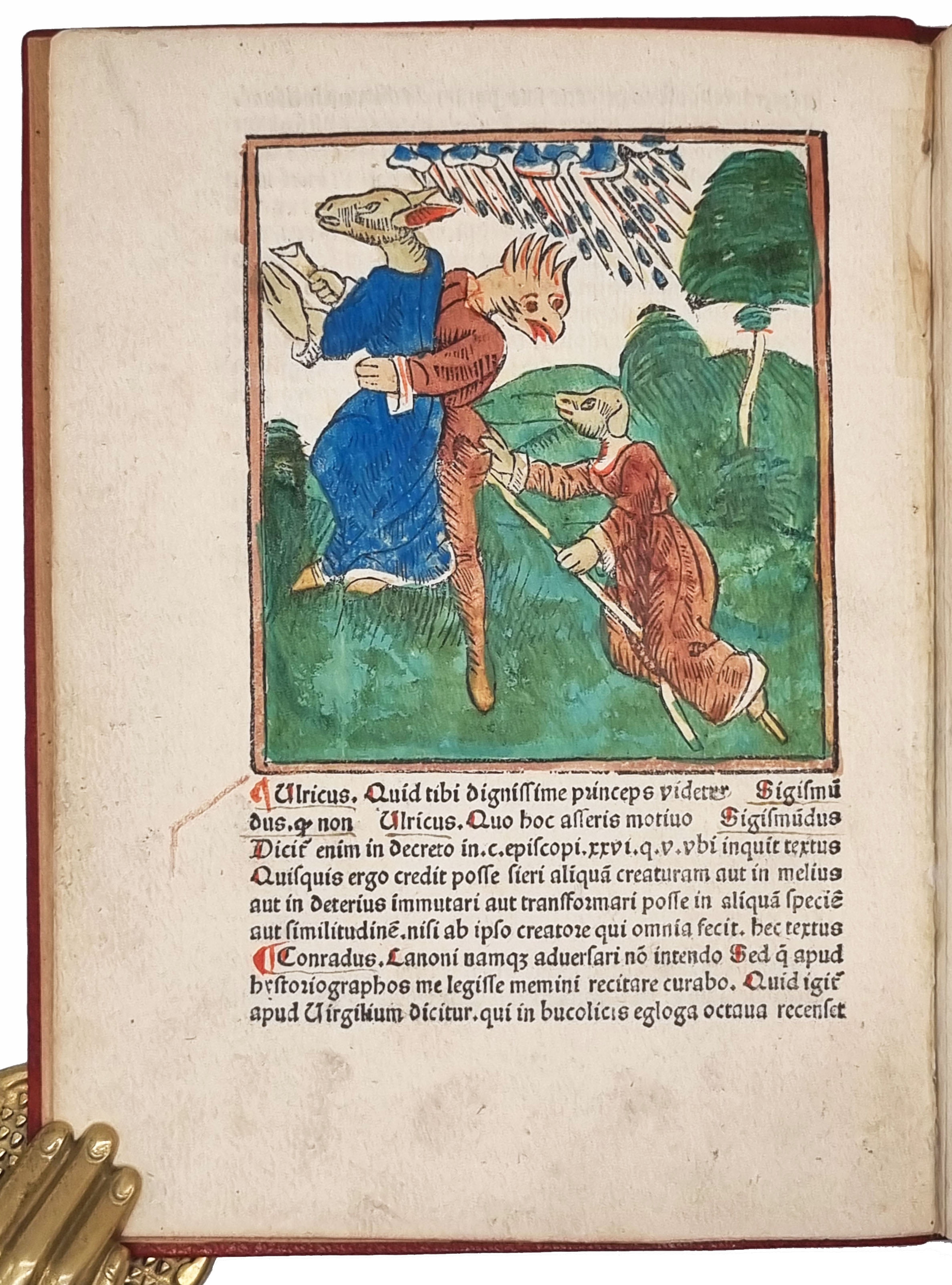

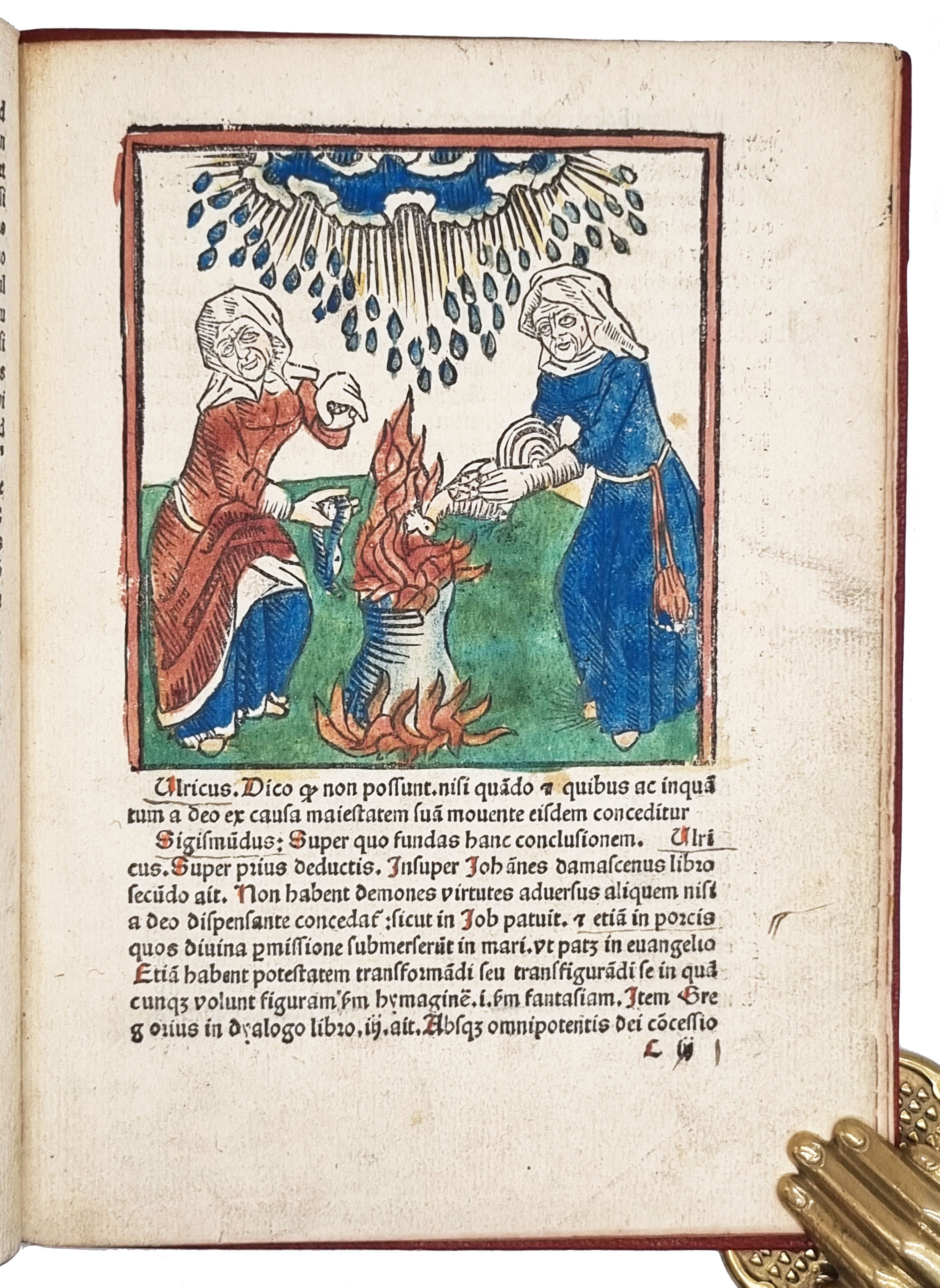

An uncommon edition of this exceptionally important text, very rarely in contemporary colouring, which has established the iconography of witchcraft in Europe until the present day. First printed about 10 years earlier with a very similar series of cuts, it is one of the earliest printed works on witchcraft and contains the first ever illustrations of witches. These vigorous iconic representations, here even more forceful for being rendered in high colour, of the hags around the cooking pot, flight by broomstick, transmuting into animals, sexual relations with men and demons, are now part of the historic ‘memory’, adopted by Hollywood, of the greater part of the western-world. Even the more sedate cut of the three witches eating beneath a tree is immediately recognisable. It was used and referred to again and again and its most celebrated verbal depiction of course is in Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Divided into nine short chapters composed in the form of a conversation between the author, the dedicatee the Archduke Sigmund of Austria and his minister Conrad Schatz, they deal respectively with the nine questions concerning witches and their harmful powers posed at the beginning of the volume. Whether by spells they could harm children, spread disease, bring on tempests, fly through the air, give birth to monsters, etc. and concluded that to a certain extent they could. “The first tract on witches to be illustrated, 1489-94, was written by the lawyer Ulrich Molitor from Constance in 1484. He actually argues against the persecution of witches because he was sceptical of the value of confessions under torture. He did, however, believe that they were heretics and should be punished with death. In the illustrations, the witches are not characterised by any special dress or undress, implying that all women were capable of being witches. They look like ordinary housewives except in the ‘Flight to the witches’ Sabbath, when they are changed into animal shapes. Although the text speaks of the witches’ evil activities being a figment of their imagination, delusions inspired by the devil, the illustrations portray the effects of their malignant and harmful magical spells as real enough, e.g. a witch shooting at a man who tries to jump away, or witches making a brew, using a rooster and a serpent as ingredients, whilst hailstones come crashing down from the sky. Molitor certainly believed in the reality of their sexual intercourse with the devil.” ‘Picturing women in late Medieval and Renaissance art’ by Christa Grössinger.

The ms note briefly describes the dialogue and its participants, referring to Molitor as ‘Chancellor’. He was appointed Chancellor of the Tyrol by Sigismund in 1494 and it is likely in a local hand.

GW 25163. ISTC im00800000. Fairfax Murray II 299 “probably the first of the five editions of this book by this printer (all undated and only one signed…)

Thirteen copies or fragments are known; only at Harvard, Yale, Morgan & Huntingdon in the U.S.In stock