MOELLENBROCK, Valentin Andras.

Cochlearia Curiosa: or the Curiosities of Scuvygrass.

London, Printed by S. and B. Griffin, for William Cademan, 1676£3,250.00

FIRST EDITION thus. 8vo. pp. (xvi) 195 (xxix). Roman letter. Four folding engraved botanical plates, good, strong impressions. Variant ed. with ‘internal or external’ in line 10 of t-p. (versus ‘internal and external’). Woodcut headpiece with arms of dedicatee. Contemp. ms. ink marks to t-p. Contemp. speckled calf, rubbed and board edges darkened, rebacked, edges sprinkled red, affecting margins of one or two ll., modern bookplate to front pastedown. A very good copy.

First English edition, translated by Thomas Shirley (d. 1678), physician in ordinary to Charles II, of this work on the natural and medicinal properties of scurvygrass (cochlearia), first published in Latin by the Leipzig physician Moellenbrock in 1674. Sherley also authored a dedicatory letter to his patron and to readers of the book, ‘of what classis soever you are.’ Indeed, this opens somewhat presumptuously: ‘I must tell you, instead of your censure I expect your thanks for the present I now make you’; Sherley also promises to please those who are ‘Chymically addicted.’

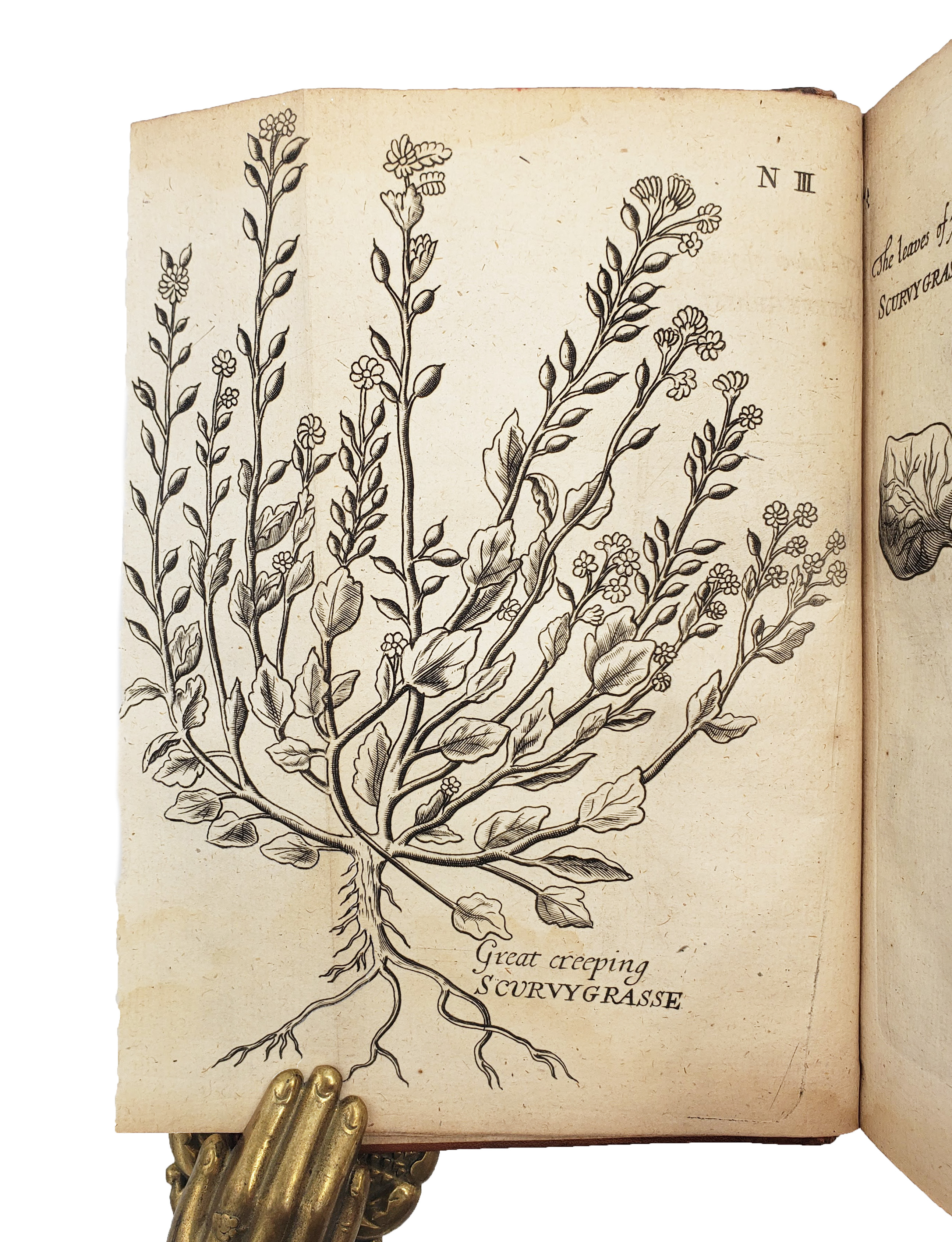

A wide range of plants are briefly and imaginatively surveyed in the proem, for example, details of a root in Judea that cannot be ‘plucked up’ until it has been ‘sprinkled with a Woman’s Urine, or Menstruous blood.’ The first chapter then considers the etymological and aetiological origins of various plant names, noting superfluously that scurvygrass is called as such because it cures scurvy; its Latin name ‘cochlearia’ is linked to the rounded shallow shapes of the leaves (‘cochlea’ being a Latin word derived from the Greek for snails, referring both their spiral shells and to the little spoons that were used by Romans to eat them), which are charmingly illustrated in the first plate, showing Dutch scurvygrass or ‘true’ scurvygrass.

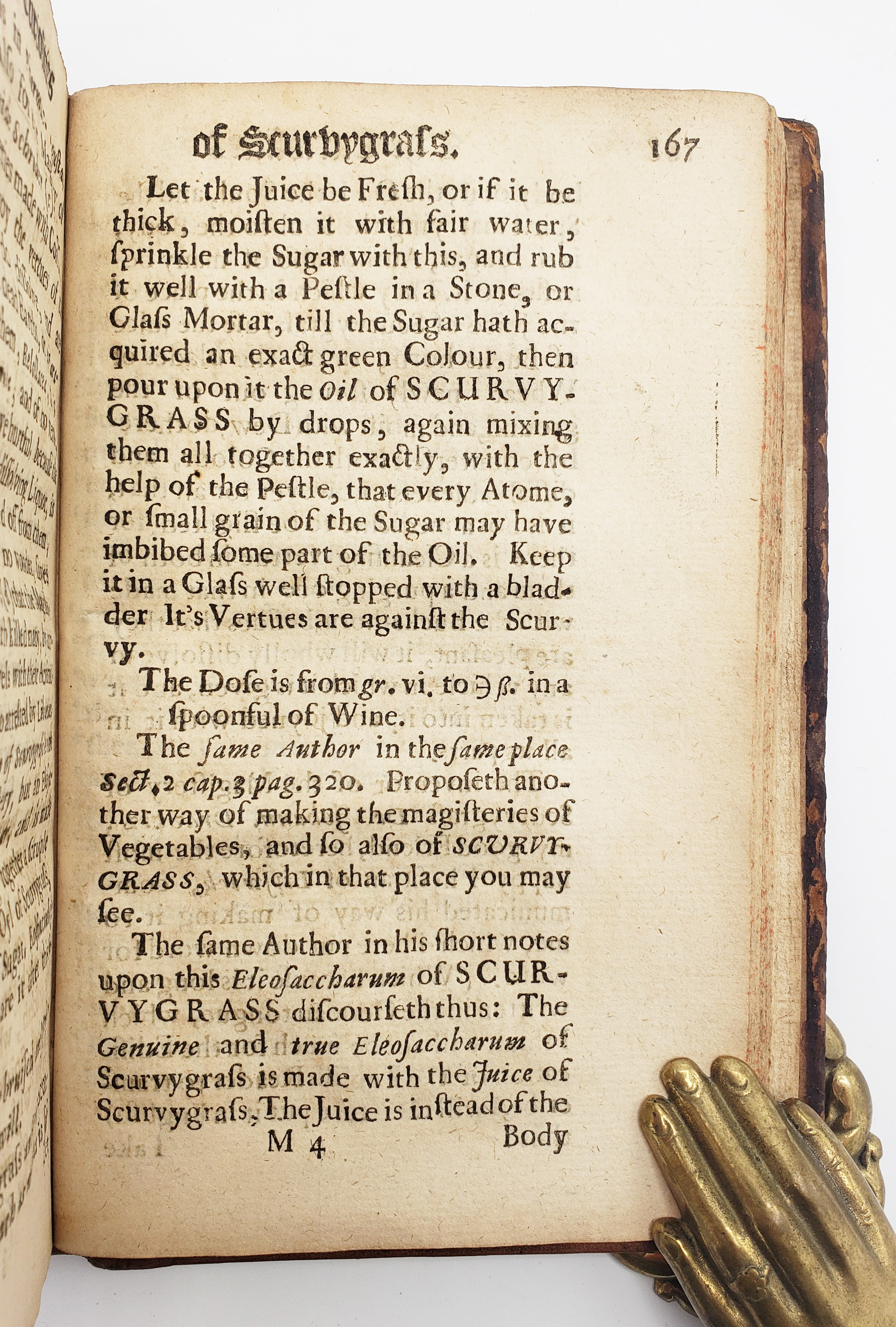

Shirley’s faithful translation leads to some confusion regarding English geography. The ‘English scurvygrass’ or ‘Britania bistort’ is shown in the plates to have different leaves to Dutch scurvygrass, being ‘un-spoon-like, as does Great Creeping scurvygrass. The bistort is useful for fastening gums and preventing teeth falling out but is otherwise not useful for treating scurvy. There is, however, another smaller plant that grows in England, resembling ‘all-seed or the little dock,’ which Moellenbrock saw used successfully on scurvy cases during an outbreak in the previous year (whether in England or Germany is not entirely clear, but presumably the latter). He notes that this plant, and true scurvygrass, can both be found in abundance by the River Thames, ‘which flows by London, and from thence to Bristol, a Port of the Western Ocean to which it moves, and by degrees increases its Floods.’ The next three chapters describe the physical properties of scurvygrass, accounting for species variation and observing that the plant only grows in Western parts of the world, namely England, lower Germany and Flanders; this is held to be a sign of God’s wisdom because it is here that scurvy is most common. Moellenbrock describes how the inhabitants of Greenland, particularly violently affected by scurvy, are also especially blessed with it in abundance, and they consume it in broth made from reindeer as a cure. The remainder of the treatise outlines the medicinal uses of scurvygrass, providing step-by-step instructions on different ways to prepare the plant as a cure, in recipes cited from various authorities: making it into wine (either with or without fermentation), cooking it into sauces (how the Norwegians avoid the disease), distilling it into waters, diffusions, decoctions, magisteries, etc. etc. Moellenbrock also provides recipes for the ‘outward’ use of scurvygrass on sores and ‘tumours’ caused by the disease, the majority of which involve mixing the plant with oil or spirit of earthworm.