GUIDI, Guido.

EXTRA-ILLUSTRATED ANATOMY

De Anatome corporis humani Libri VII.

Venice, apud Iuntas, 1611£7,500.00

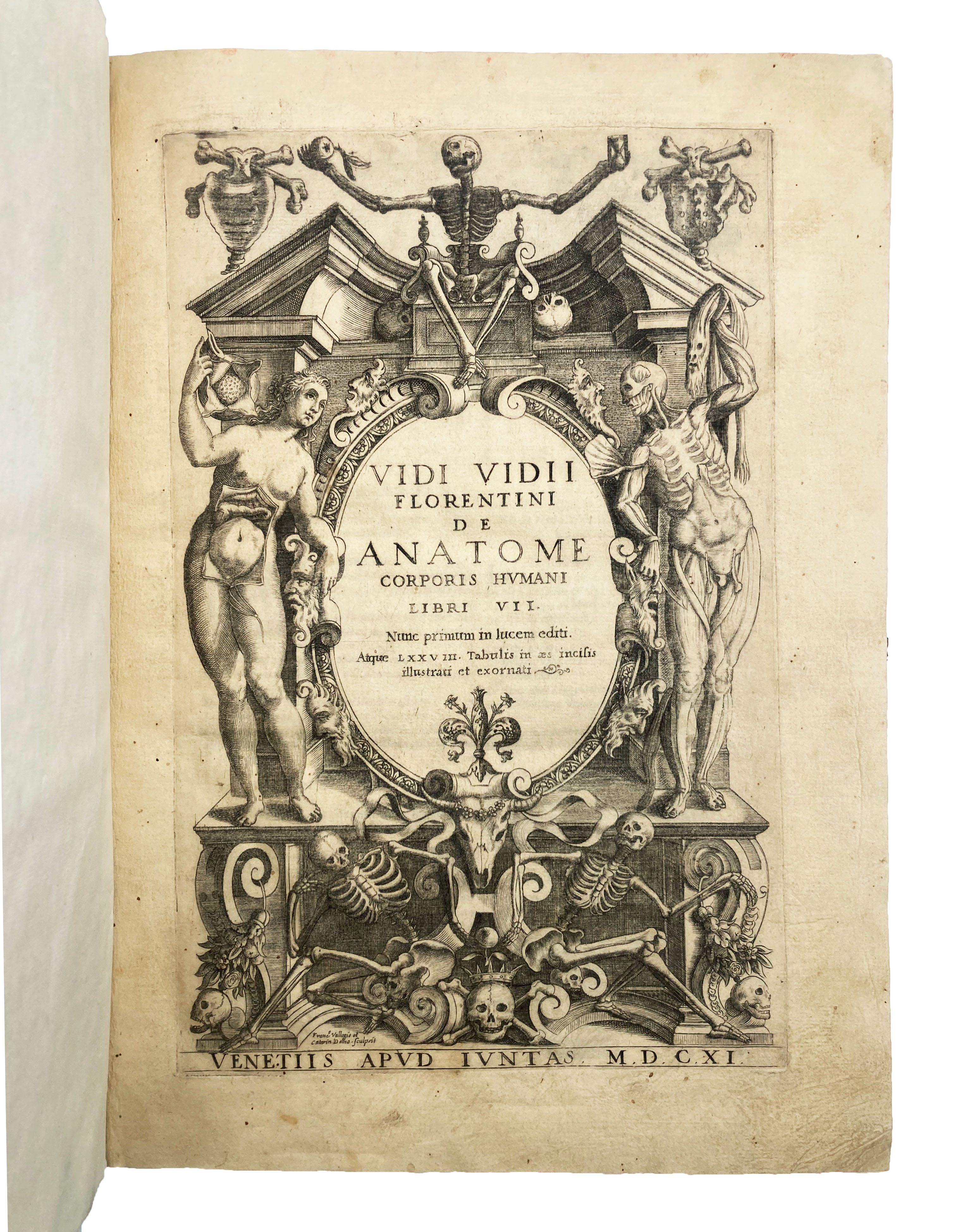

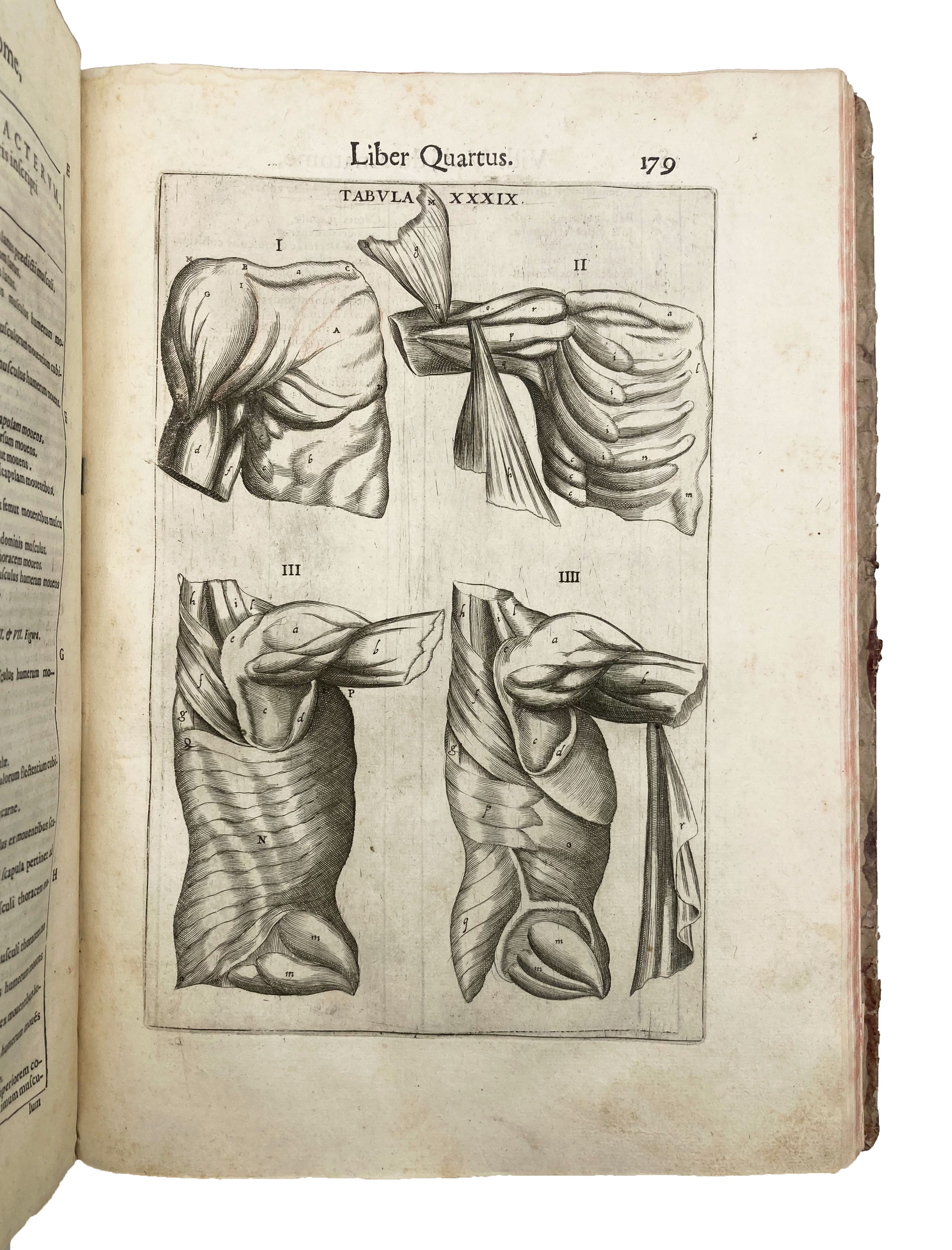

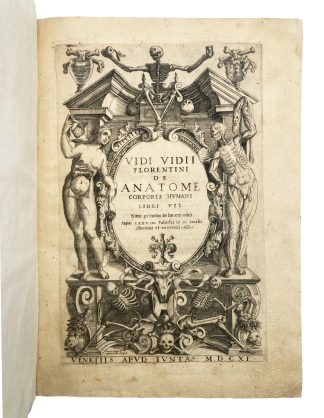

FIRST EDITION. Folio. pp. [16], 342. Roman letter, with Italic. Engraved title with skeletons, anatomical figures, and memento mori, signed Francesco Vallegio and Catarin Dolno, 78 exquisite full-page engraved anatomical illustrations, added plate signed J. Pecini f.[ecit] Venetiis interleaved between pp.32-33, decorated initials and ornaments. Title lightly browned, minor repair at blank gutter of C2-4, couple or so purplish ink stains at blank gutter of final gatherings, last leaf strengthened at gutter. A good, well-margined copy in C18 quarter vellum over marbled paper boards, C20 bookplate of E. Malan de Merindol to front pastedown.

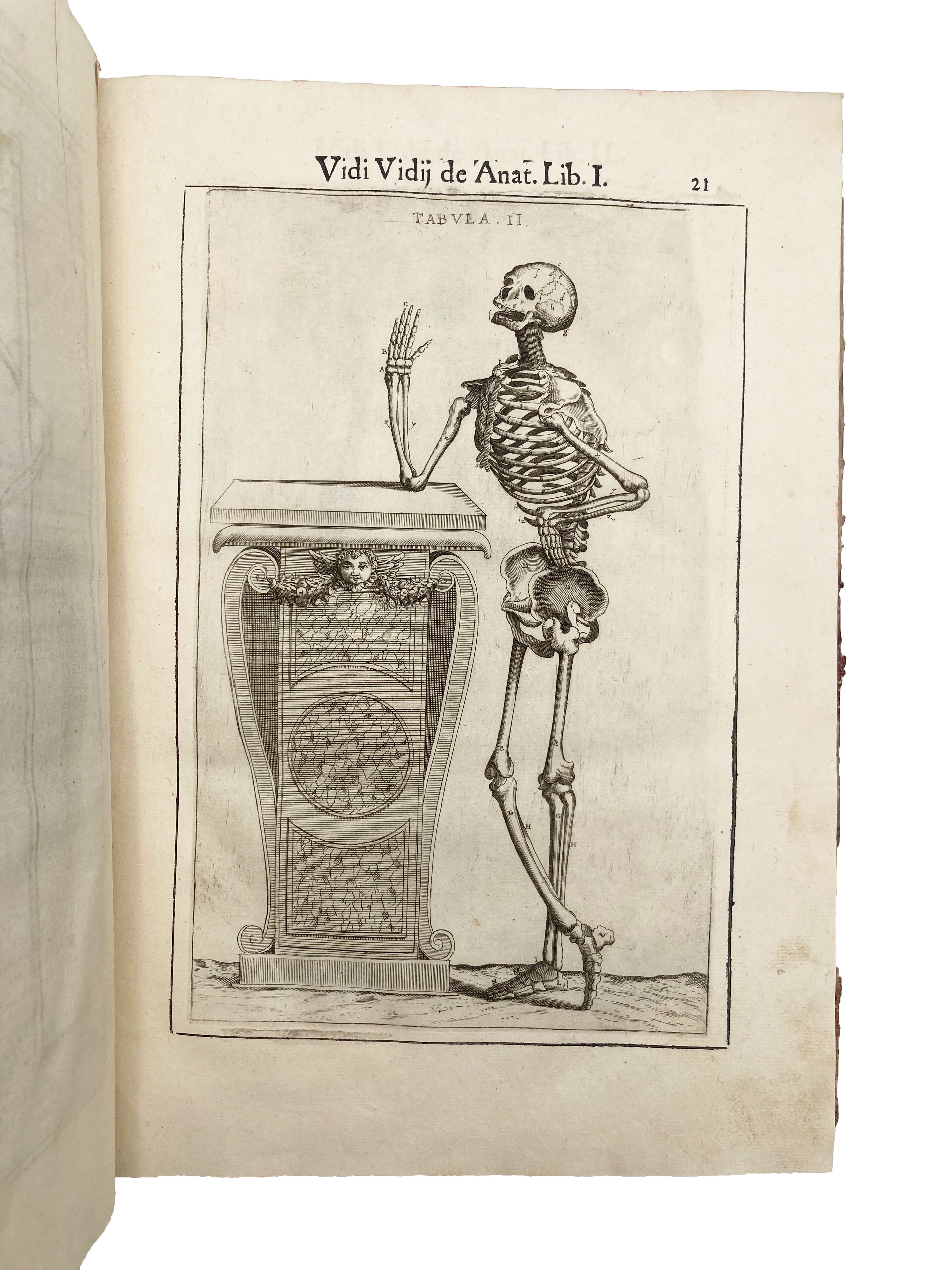

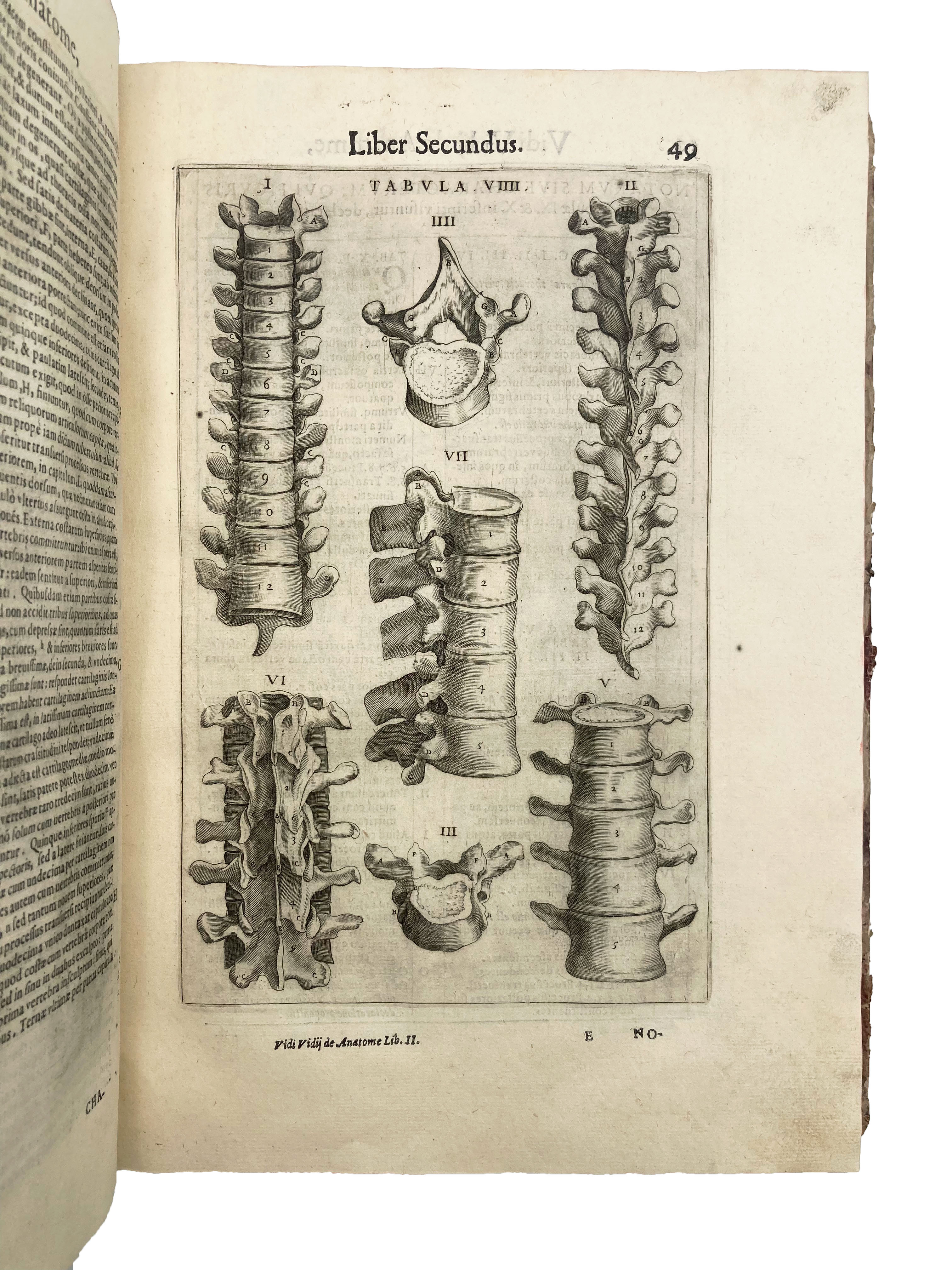

A good copy of this copiously illustrated anatomical manual with the plates in nice, clear impression. The Florentine surgeon Guido Guidi (Vidus Vidius, 1509-69) was Francis I’s personal doctor from 1542-7, and later Cosimo de’ Medici’s. He also published ‘Chirurgia’ (1544) – a commentary on a C10 Greek medical ms he had brought as a present to the King of France. ‘Guidi’s anatomical studies [for ‘De anatome’] were performed at the University of Pisa after his return to Italy in 1548 but were not published until many years after his death when his nephew compiled and edited them. This long delay may account for the fact that the book received little acclaim even though his descriptions of the vertebrae, cartilaginous structures, and bones of the skull were better than those of his predecessors. Guidi also made original studies on the mechanics of articulation in the human body and described the anatomical structures in the pterygoid bone that bear his name. Some of the figures in the seventy-nine engraved copperplates were adapted from Vesalius, a fact which Guidi states early in the book’ (Heirs of Hippocrates). ‘The plates are mostly new and original’ (Choulant), inspired by Eustachius and Vesalius, but also by Valverde’s anatomical book. The seven parts discuss the nature of surgery, the compass of the work, surgical skills and instruments, as well as procedures and treatments for conditions pertaining to bones, cartilage, ligaments, nerves, blood vessels, muscles, the chest and abdomen, and the ‘vital body parts’ essential to life (e.g., neck, throat, lungs, heart, etc.). The handsome illustrations refer back to tables providing captions to the anatomical parts marked by letters. The last section is devoted to the detailed anatomy as seen after dissections, with handsome engravings of the brain and the eyes, with the last chapter focusing on differences between the dissection of corpses and of living beings, providing a lifelike picture of dissection practices in the mid-C16.

The additional engraving – signed Giacomo Pecini (1617-69), a Venetian artist and printmaker, deserves its own description. It comes from the very slim, ground-breaking pamphlet by Cecilio Follio called ‘Nova auris internae delineatio’ (first ed. of 1645). The plate illustrates six parts of the middle and inner ear – the subject of the work – which had not been previously observed in such detail. This plate has no letterpress text on the verso, suggesting it was sold separately.

Krivatsy 5115ff. (later eds); Heirs of Hippocrates 265; Choulant-Frank, p.212; Garrison-Morton 380. Not in Wellcome or Osler.