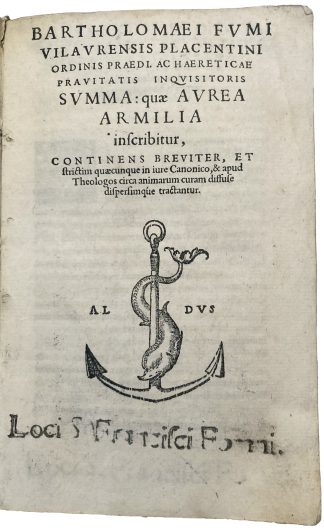

FUMO, Bartolomeo.

CANON LAW, INCLUDING PHYSICIANS’ SINS

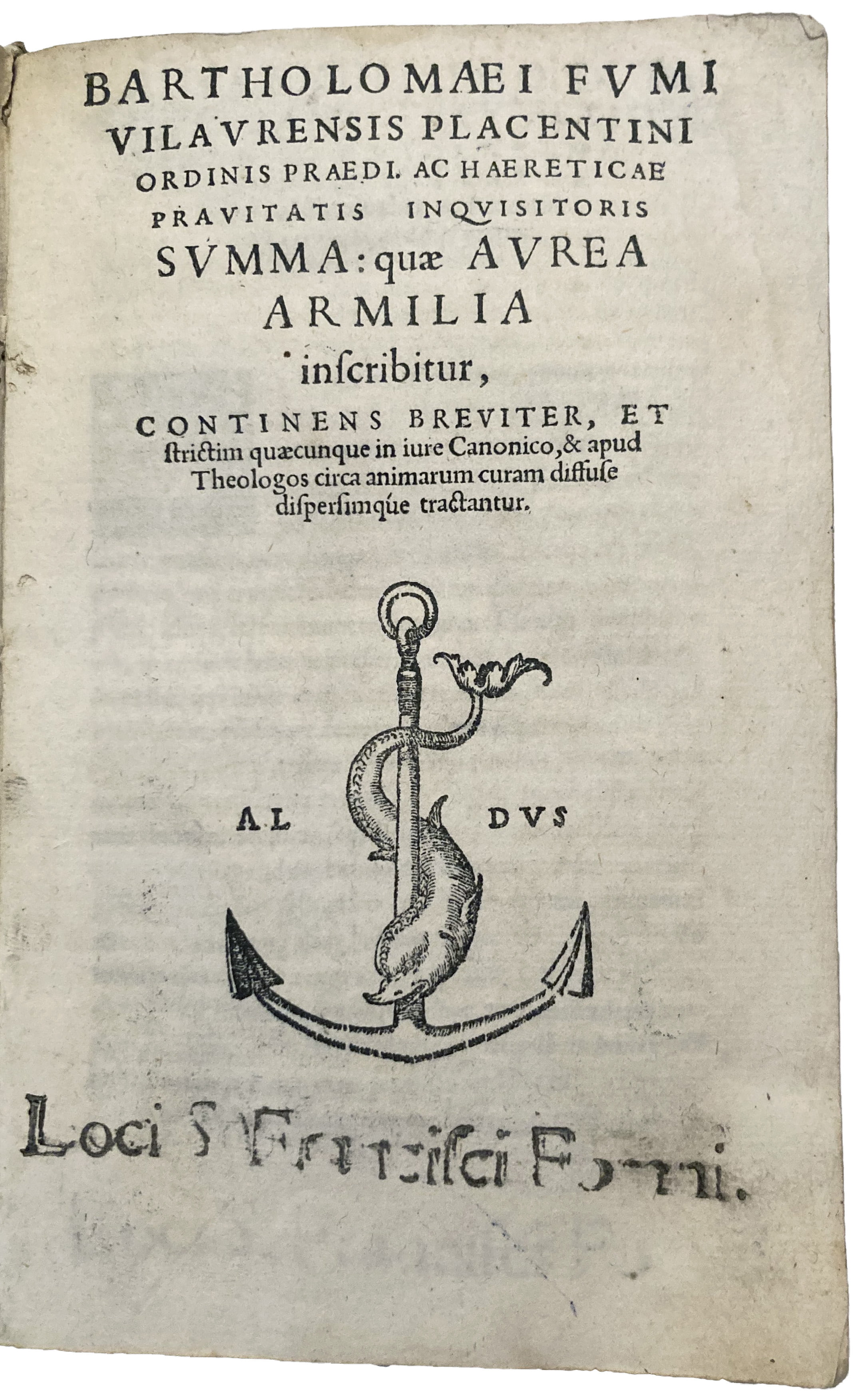

Summa, quae Aurea Armilia.

[Venice, Paulus Manutius, 1554.]£4,950.00

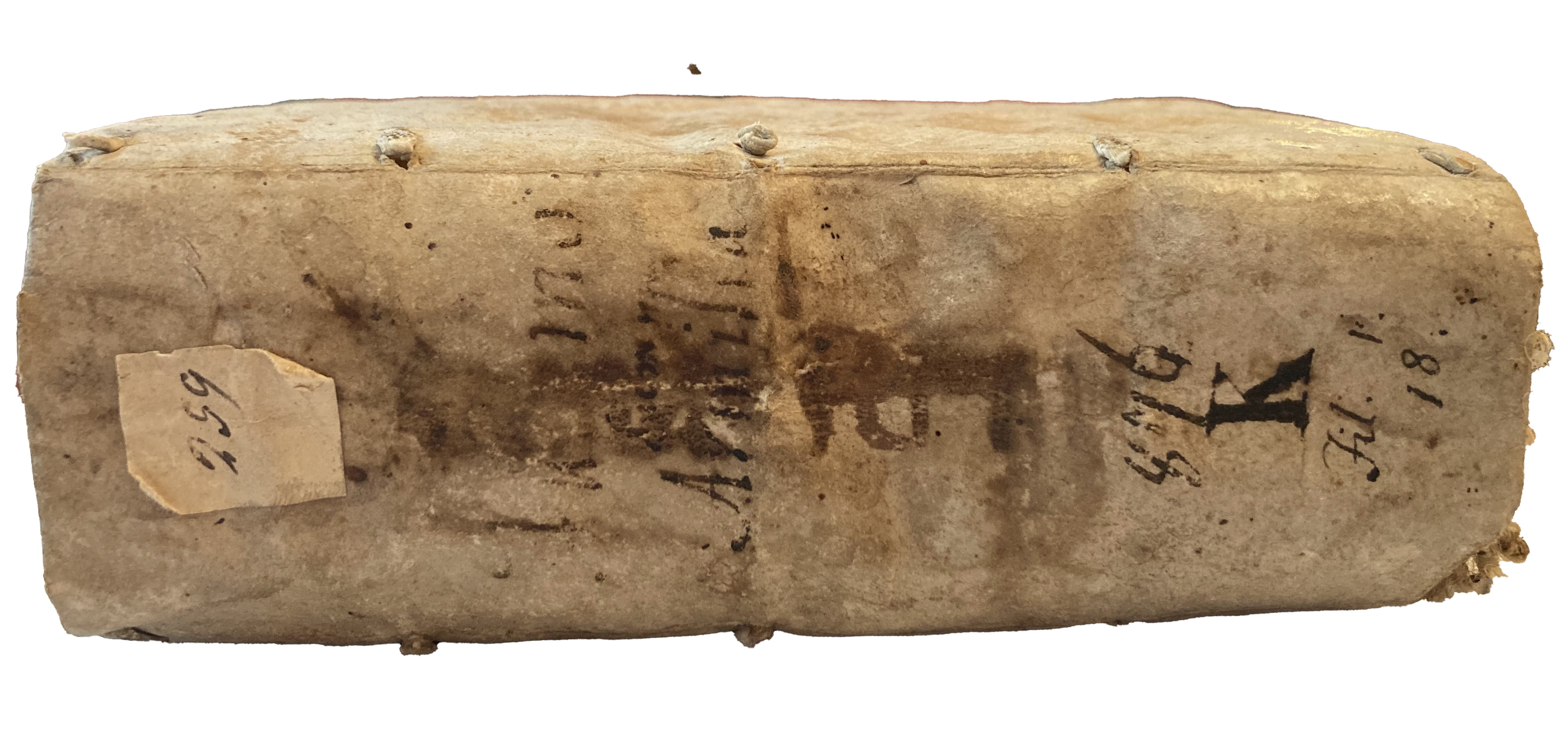

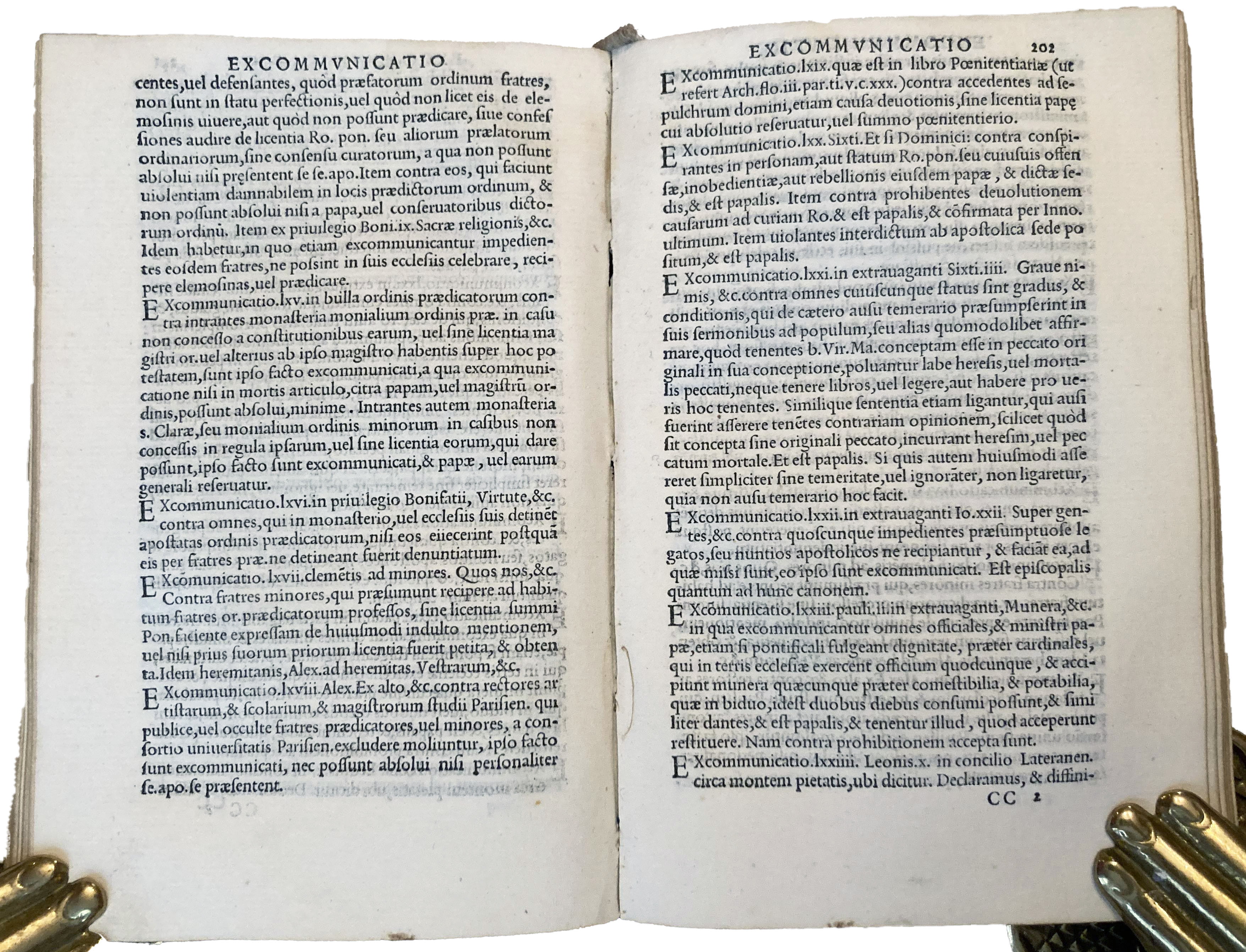

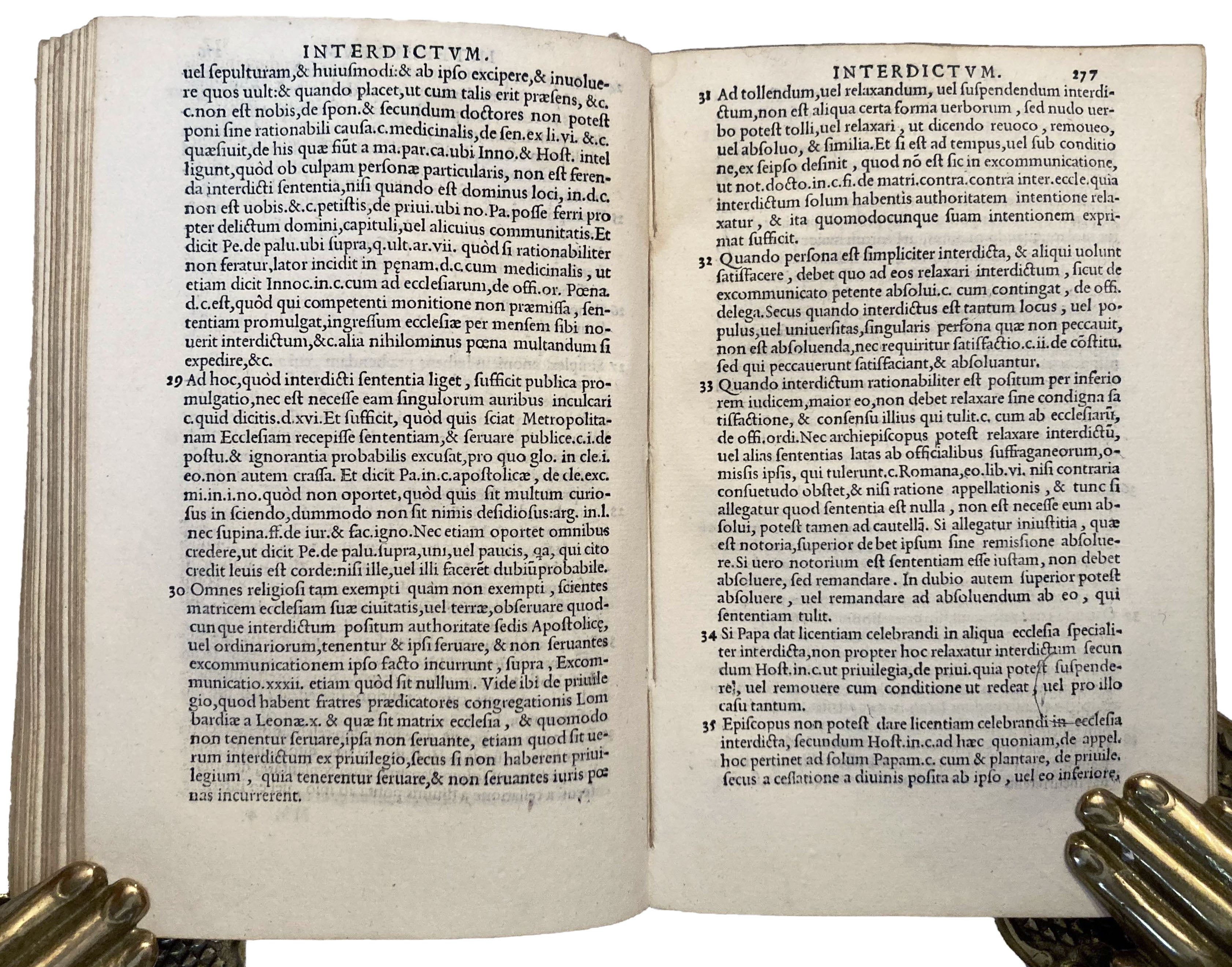

8vo. ff. [8], 468 [i.e., 496]. Roman letter. Woodcut dolphin device to title, full-page genealogical tree of consanguinity to 2V5 verso, two small printed diagrams. Few lower edges untrimmed, very faint water stain just in the outer blank margin of first 4 ll. and upper gutter or margin from HH onwards. A very good, clean copy in contemporary limp vellum, lacking ties, yapp edges, two early ms titles (older one, vertical, smudged), shelfmark and later paper label to spine, traces of chewing to upper cover fore-edge, C17 stamp ‘Loci S. Francisci Forani’ to title and first , slightly later ms ‘Frater Joannes’ to rear ep, small tipped-in paper slip, probably in his hand, with ‘Laus deo patri summo (?) et deus’ on both sides, and ‘Jo[annes] Fra[nciscus?] Verg[i]lio da Cingoli’.

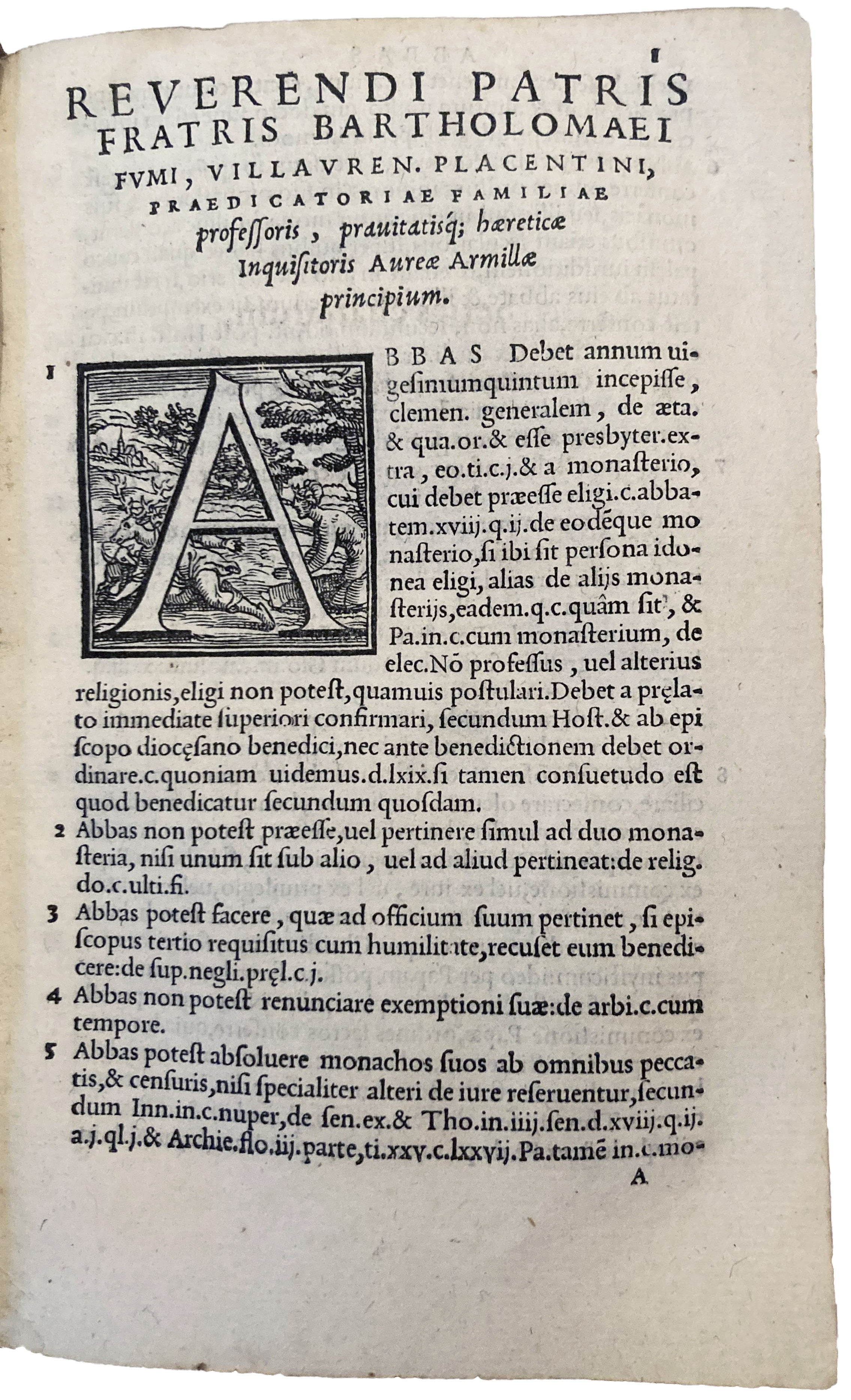

A very good copy of the second edition of this ‘pocket’ compendium of canon law. Legal Aldines are uncommon. The Dominican theologian Bartolomeo Fumo (d.1545), was inquisitor in Piacenza, where the ‘Summa’ was first published in 1549. Popular and much reprinted, it is a compendium of cases of conscience, i.e., a manual detailing, in 504 sections, with the ethical and moral conundrums priests and confessors were most likely to encounter, and which they had to address according to ecclesiastical law. The present copy was in the library of a Franciscan monastery near Rieti, in Italy. The work is prefaced by a copious index for easy consultation. In addition to topics such as the capital sins, sacraments, excommunication and the regulations of marriage (illustrated by an ‘arbor consanguinitatis’ showing the degrees of kinship between spouses allowed by the Church), one also finds hundreds of situations of family law (e.g., adultery, bigamy, financial debt towards one’s spouse, inheritance), ‘anti-social’ behaviour (e.g., bestiality, sodomy, fornication, incest, murder, prostitution), or activities that contravene Christian doctrines. Among these are alchemy – an ‘art that is not itself illicit, if done without fraud, nor is it a sin to sell what is produced through alchemy, unless one is selling something which is actually not what it looks like’ – and necromancy, a mortal sin of ‘divination through demons who take the shape of dead people’. Most interesting is the section, one of several which focus on specific professions or offices, about the proper conduct of physicians: ‘Physicians may sin in many ways.’ Mortal sins for doctors include ignoring an ailment, requiring extortionate fees, refusing to research an illness they are unfamiliar with, or to visit or administer medicaments, distributing remedies that are ‘not prepared according to the art of medicine, but according to their stolid fantasy and experiments’, and refusing to urge very sick patients to receive confession, depending also on whether the physician is wealthy or paid by the community. A remarkable glimpse into the everyday mid-C16 life.

Renouard 280:14; Ahmanson-Murphy 461; Adams F1161; BM STC It., p.263.In stock