DELMEDIGO, Joseph Solomon.

‘THE FIRST JEWISH COPERNICAN’

ספר אלים. [Sefer Elim].

Amsterdam, Menashe ben Yisrael, 388-389 [1628-29].£19,500.00

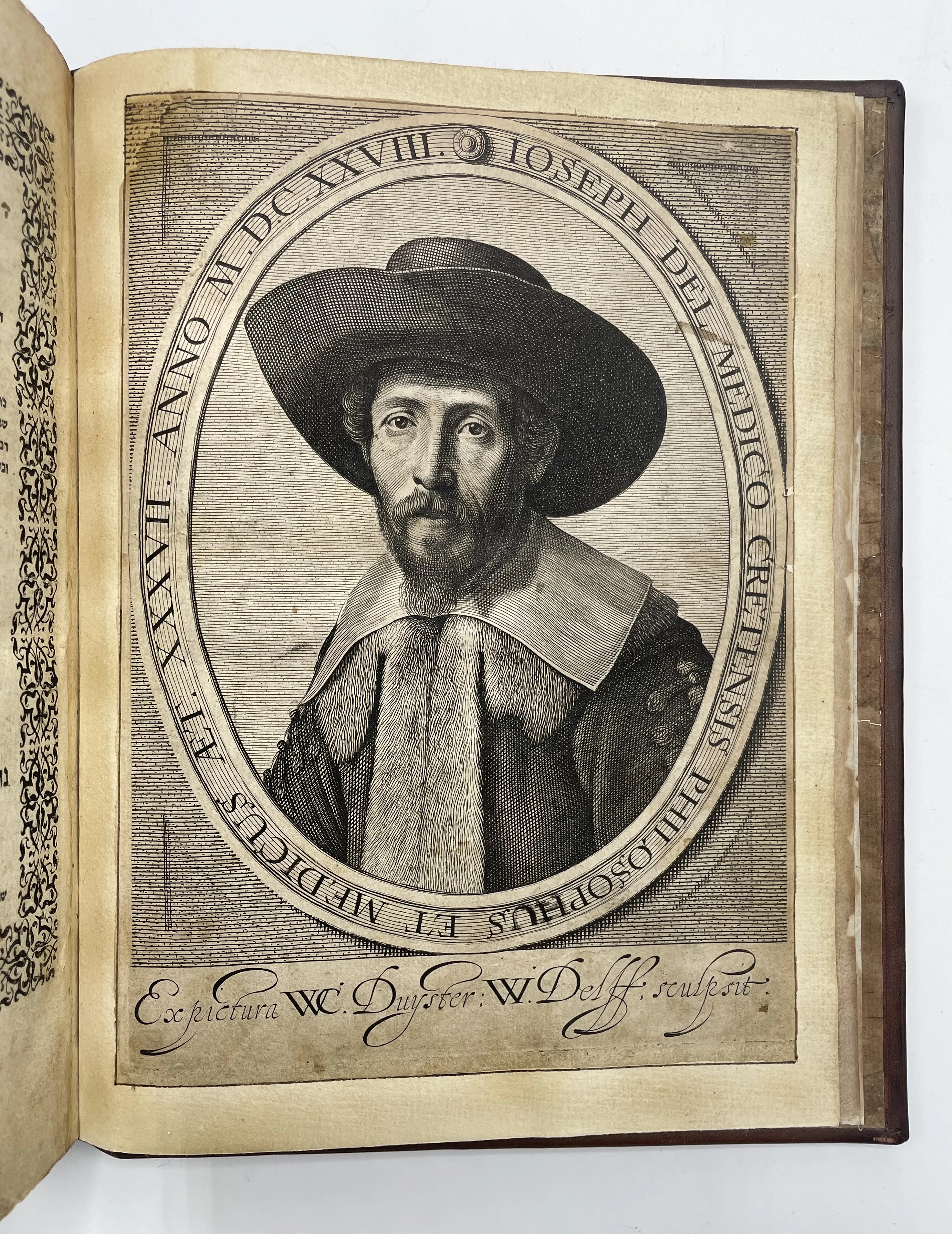

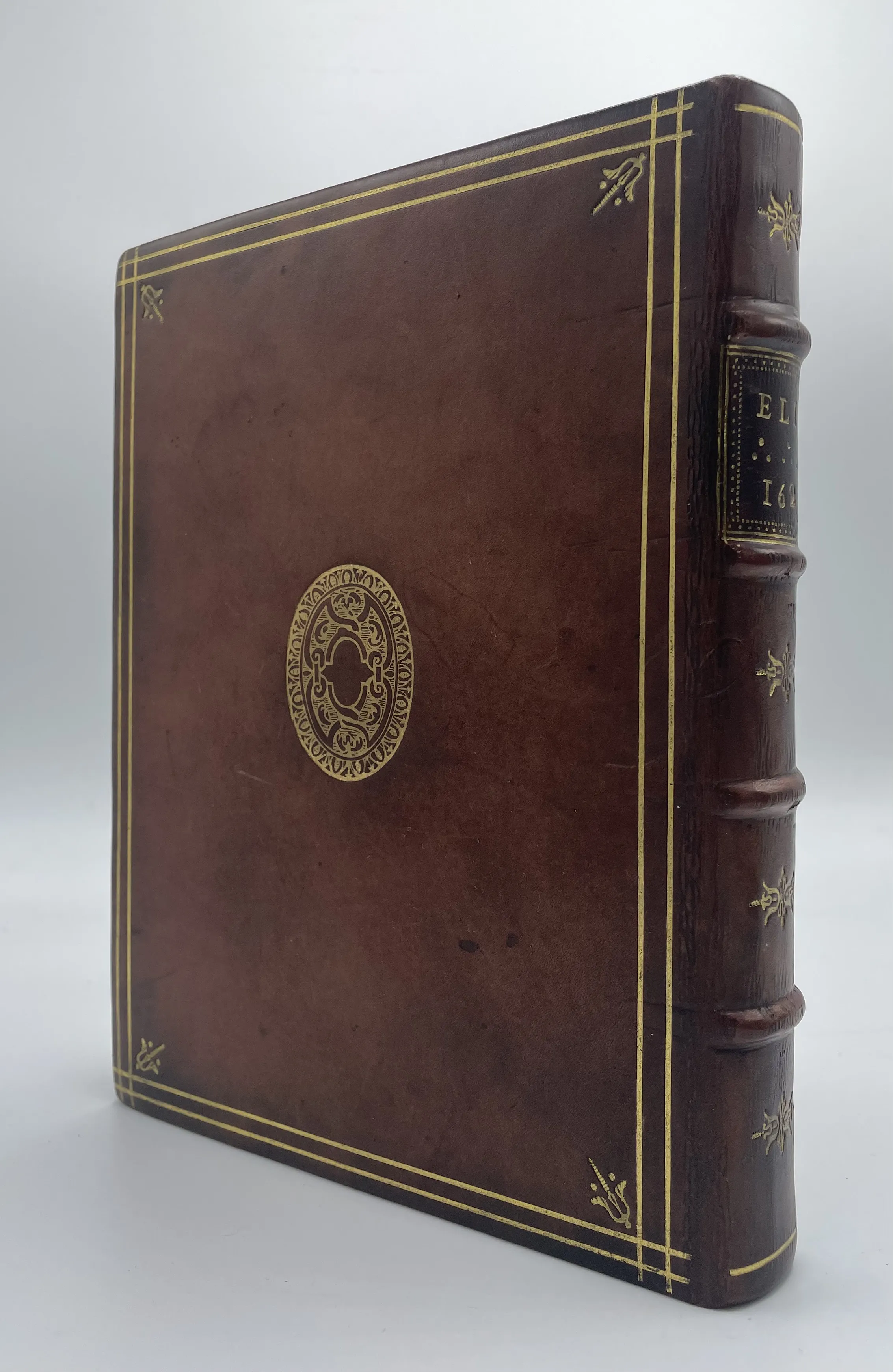

FIRST EDITION. Small 4to. 3 parts in 1, separate t-ps to two: engraved portrait (which collates as part of Sefer Ilem), I: Sefer Maʻayan ganim, pp. [2], 192; II: Sefer Maʻayan ḥatum, pp. 80; III: Sefer Ilem, pp. [4] [=misbound as prelims of II], [4], 83, [1]. Hebrew letter. Engraved author’s portrait (trimmed and mounted), repair to verso, typographical border to t-ps, astronomical and scientific diagrams, decorated ornaments. Occasional slight browning, a little light age yellowing, few ll. a little foxed at margins, first title and last leaf strengthened at gutter. A very good, wide-margined copy in modern polished calf, gilt, morocco label, original eps, early Hebrew ms to eps and first title.

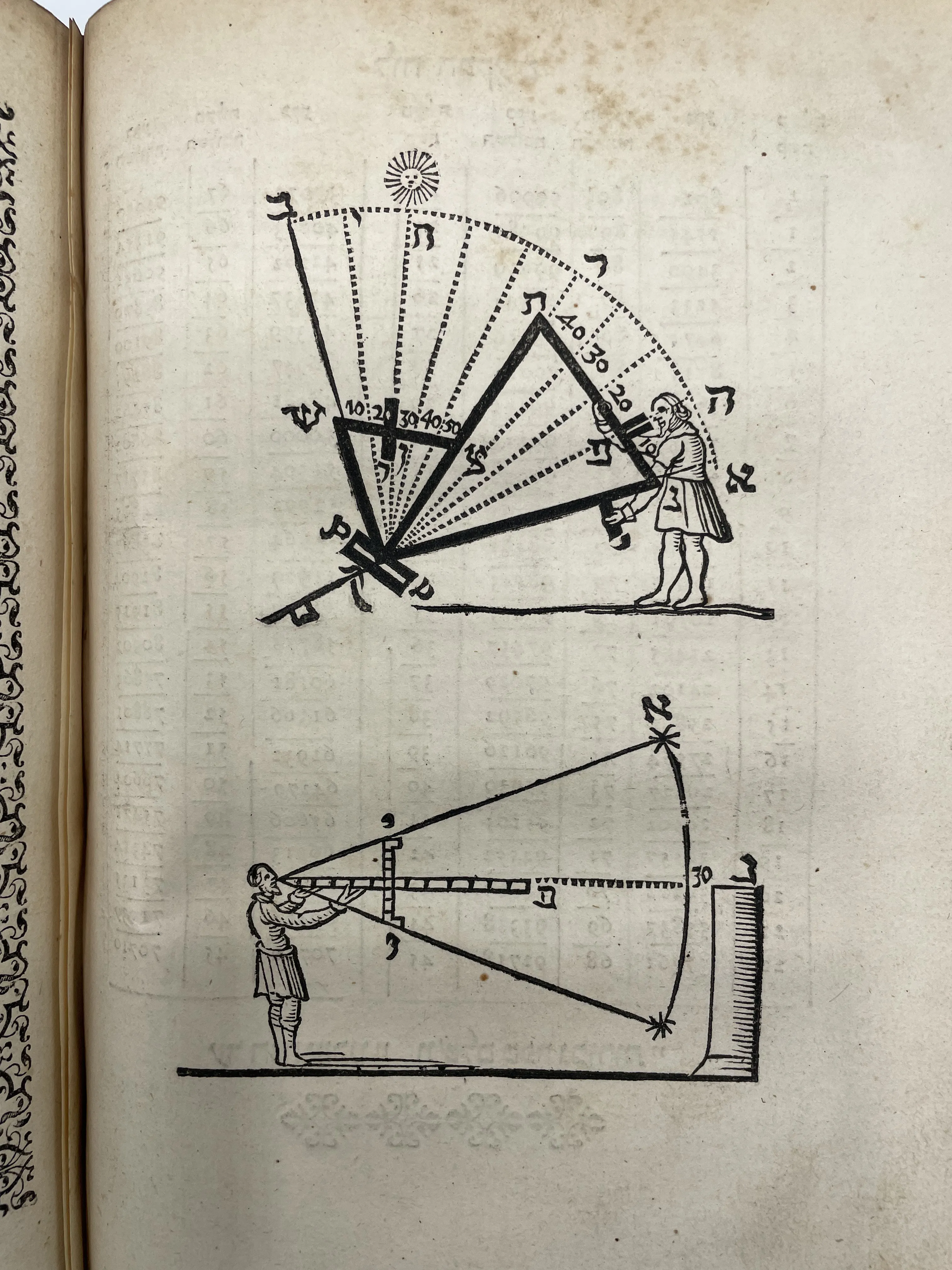

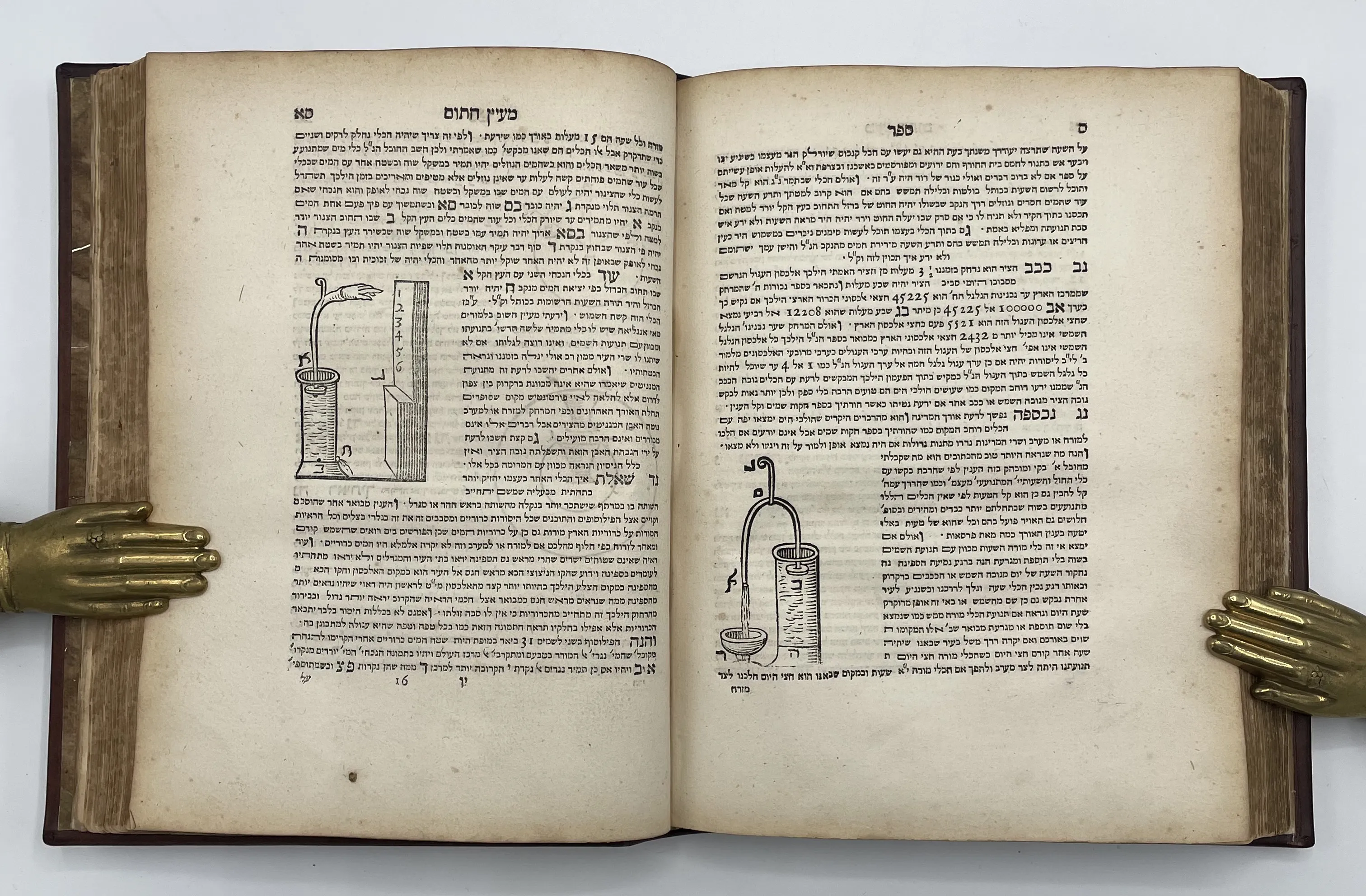

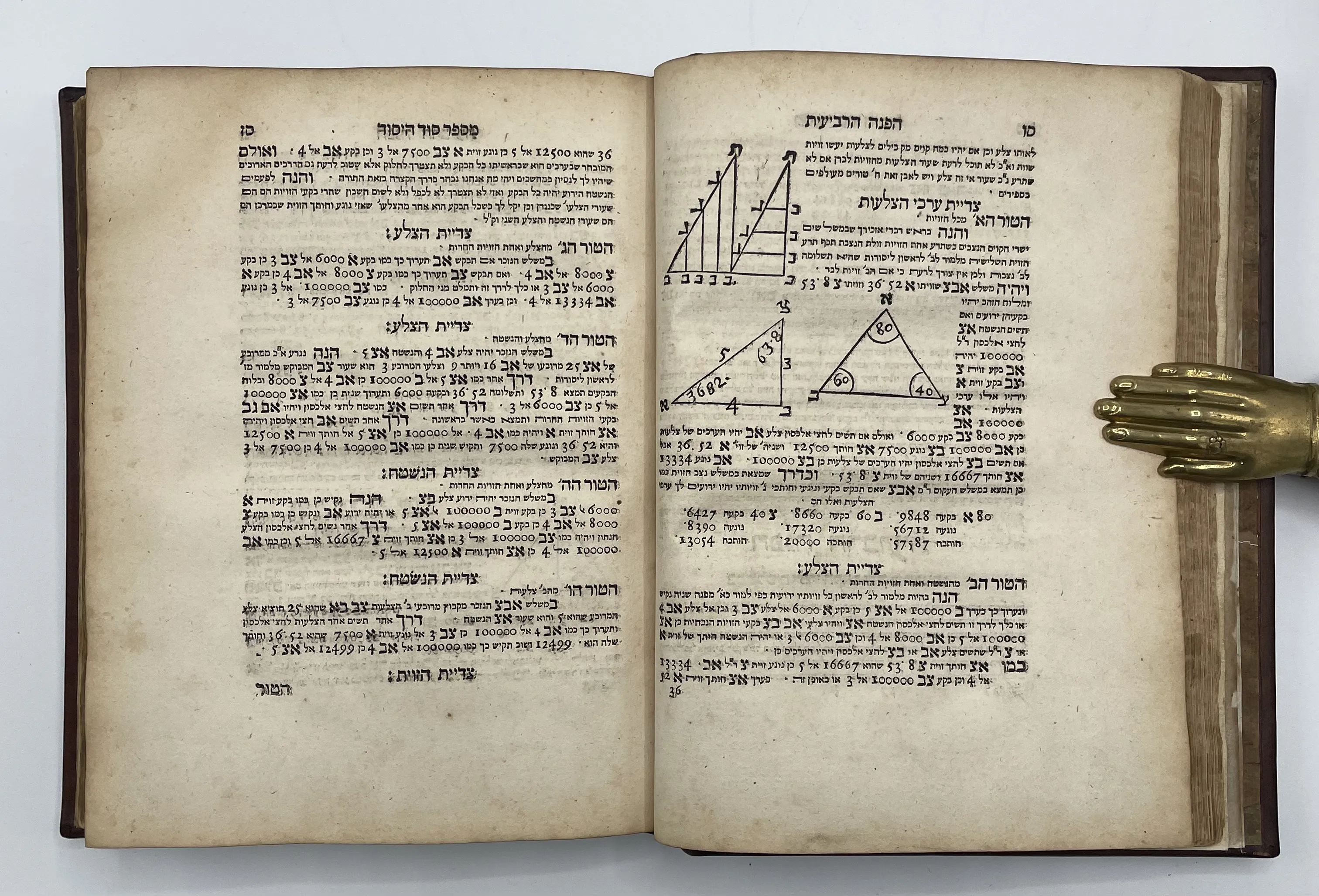

First edition of this extensively illustrated, most important Hebrew work on astronomy, mathematics, natural philosophy, music and geometry, written by ‘the first Jewish Copernican’, student of Galileo and a major influence on Spinoza. Joseph Solomon Delmedigo (1591-1655) was a rabbi, physician and polymath from Crete. At Padua, he studied medicine and attended Galileo’s astronomy lectures 1609-10. After a brief stay in Venice, he journeyed the Middle East, eventually settling in Amsterdam in 1623, where he wrote ‘Sefer Elim’, his only known work. It is divided into two separately titled parts—‘Sefer Elim’ and ‘Ma’ayan Ganim’—the latter subdivided into four essays on astronomy, mathematics, the consonance of music and biblical passages in relation to the scientific method. ‘Sefer Elim’ is a reply to 12 broad and 70 specific questions posed in letters, reproduced at the beginning, by the Karite scholar Zerah. Delmedigo’s answer discusses Aristotelian natural philosophy, spherical trigonometry, celestial bodies, comets and the workings of the lever, illustrated with diagrams and illustrations. Whilst Delmedigo’s in-depth analysis of Copernican theories was left unpublished and is now lost, his circumscribed references in ‘Sefer Elim’ are nevertheless revealing. ‘Part of Delmedigo’s support for the Copernican model is to be found in his criticism of the Aristotelian conception of the universe […] By rejecting this idea, Delmedigo not only took on the accepted scientific views of the past, but also challenged the Jewish model of the universe, which was based on Aristotle’; he also stated that the universe was possibly infinite and included other solar systems (Brown, ‘New Heavens’, 70). He mentions studying with ‘his teacher Galileo’, as he describes their observation of the sky and planets through the famous telescope; however, scholars believe Delmedigo became familiar with Copernicanism elsewhere, as until 1610 Galileo was not publicly or privately endorsing this theory (Brown, ‘New Heavens’, 74). The epistemological inconsistencies of ‘Sefer Elim’ derive from Delmedigo’s complex relationship to the Scientific Revolution and Cabala-informed Jewish culture, resistant to the new method. As proved by the very title—a reference to the fountains of wisdom—he linked ‘Jewish-hermetic revelation with Copernican cosmology and sought material objects such as ancient Hebrew mss that, purportedly, maintained a stronger connection to the revelation’, seeking to connect Jewish theology and Copernicanism (Ben-Zaken, ‘Cross-Cultural’, 78). The work ‘became suspect in the eyes of the elders of the Sephardic community, and a committee was formed to investigate the matter. The book had to be translated orally into Portuguese’; the printer had to declare officially that certain portions would not be published, though by then Delmedigo had moved elsewhere (Heller, ‘C17 Hebrew Book’, 471).

This copy preserves the Latin dedication to the reader, often absent.

Heller, C17 Hebrew book, 470-71; Bib. Hebr. Book, 10125944; Steinschneider, Cat. librorum hebraeorum, 1510-1511, 5960/1-3; Wolf, Bibliotheca Hebraea, I, p.566, n.976. J. Brown, New Heavens and a New Earth (Oxford, 2013); A. Ben-Zaken, Cross-Cultural Scientific Exchanges in the Eastern Mediterranean, 1560-1660 (Baltimore, 2010). Not in Riccardi, Houzeau-Lancaster or Lalande.In stock