CULPEPER, Nicholas

MAVERICK HERBALIST’S GIFT TO HUMANITY

Culpeper’s Last Legacy: Left and Bequeathed to his Dearest Wife, for the Publick Good.

London, printed for Nath. Brooke at the Angel in Cornhil (sic), near the Royal Exchange, 1676 [1677].£1,450.00

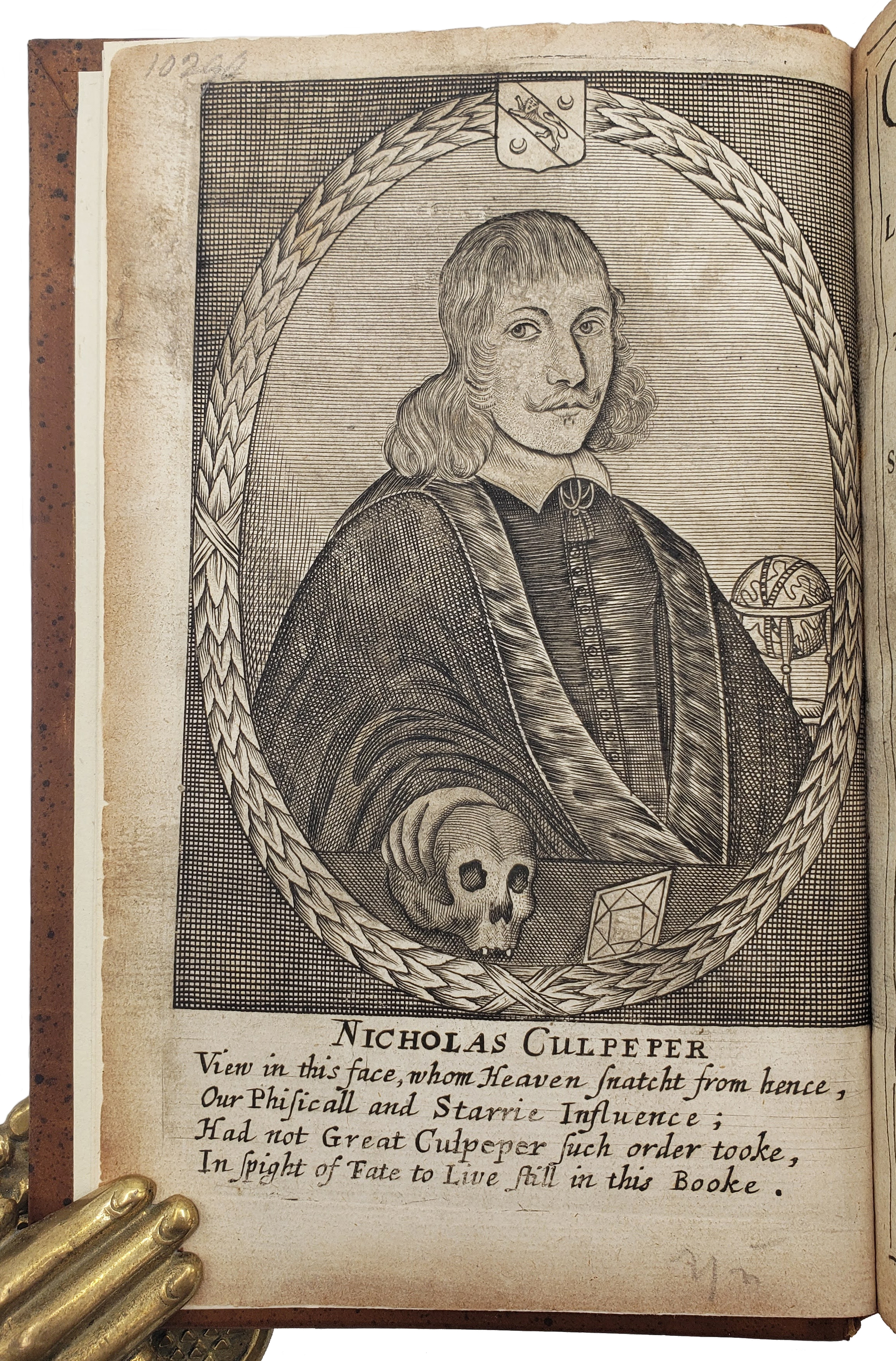

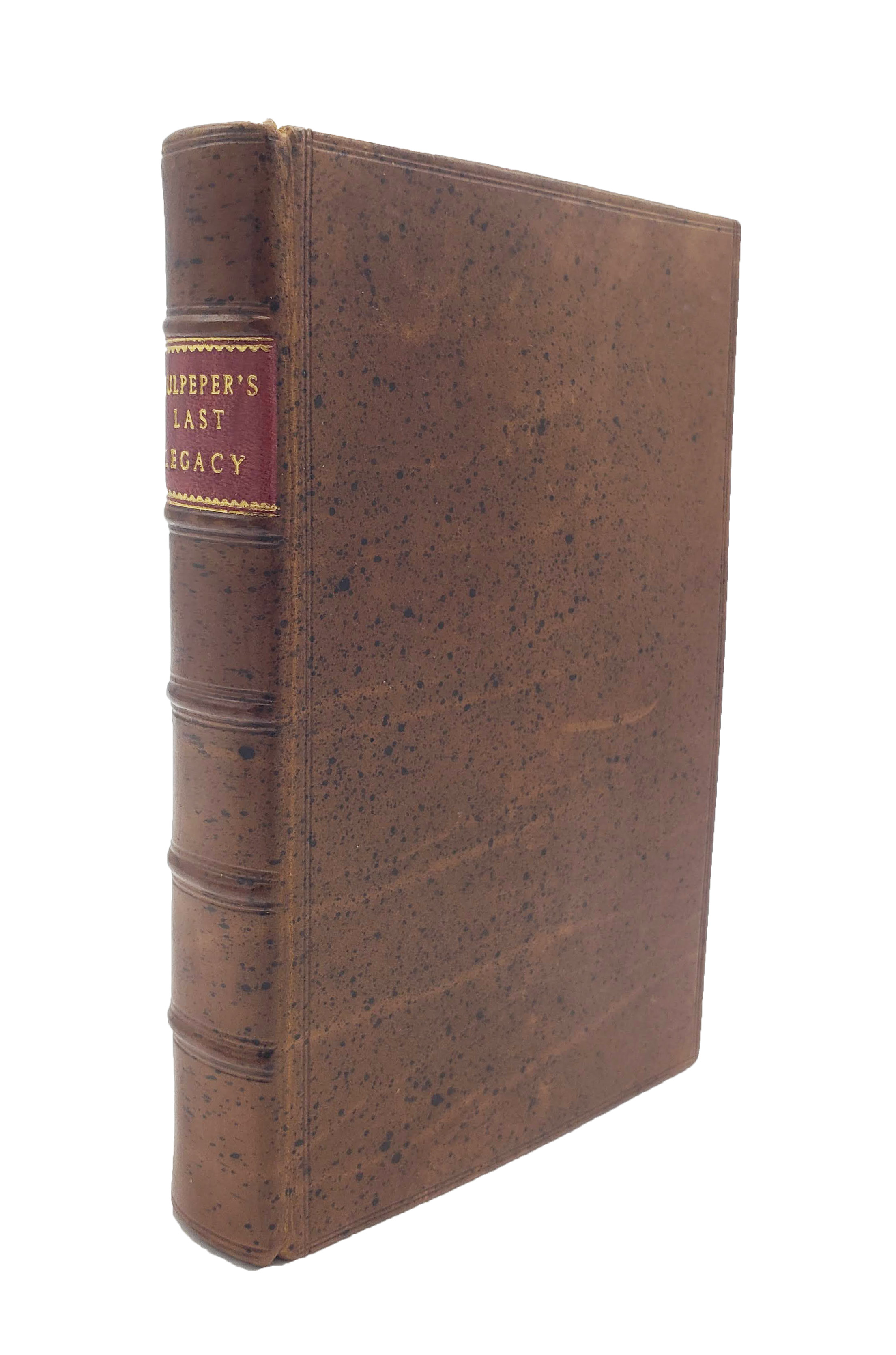

8vo. [8], 276, [16], 60, [18] pp. Roman letter, separate titlepage for each of the nine books, engraved memento mori portrait of author on frontispiece accompanied by epitaph. Light soiling to t-p and frontispiece, light marginal stain in places, intermittent light browning and spotting mostly marginal. 17 pages of publisher’s advertisements, several titles underlined. A good copy in modern old-style speckled calf, covers double blind ruled, spine with five raised bands, compartments blind ruled, red morocco label with gilt lettering to second compartment, edges speckled red.

A good copy of the 1677 reissue of the fifth edition, published the previous year, by the idiosyncratic physician and astrologer Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654). A proponent of astrological medicine and herbalism, he was seen by the burgeoning medical establishment as a “vituperative quack” (Poynter) and enemy of progress; to others he was a Robin Hood-type figure whose republican beliefs spurred on his quest to make medicine accessible to ordinary people. In the preface, he makes clear that his wife, Alice Culpeper, was to publish this book of his “Choysest Secrets” posthumously for the benefit of the public. This edition includes Book IX for the first time, with further remedies and treatises not published during Culpeper’s lifetime. Like the other books in this collection, he not only draws from a wide variety of sources such as Galen, Aristotle, Mizauld, Albertus Magnus, and Scribonius, but he also goes to great lengths to emphasise his knowledge gained from “constant practice.”

Book I covers headaches and various distempers, outlining causes such as cold, heat, plenitude of blood and windiness. Book II concerns the treatment of fevers; Culpeper draws on Hippocrates’ theory of the body being divided into three parts – the humours, the flesh which contains the humours, and the spirit which animates both – and extrapolates that fevers can occur in all three as a result of “unnatural heat.” Book III is a collection of 300 remedies against diverse diseases. Book IV is a treatise on pestilence, which he wrote for the benefit of posterity so that they might aid themselves and their fellow citizens (without having to rely on physicians). He identifies three interlinked causes of pestilence: the “great Conjunctions of the Superior Planets meeting in the Signs,” the Air that is unwholesome and corrupted as a result of this conjunction, and the putrefied humours caused by breathing such air. Book V is a synopsis of compositions used by physicians and chemists, organised into categories such as waters, syrups, wines, oils, salts, and pills. The information is presented in a series of tables for ease of understanding. Book VI covers the qualities of medicines, while Books VII and VIII describe the application of such medicines to parts of the body, beginning at the head. Book IX is a new addition to this fifth edition, “Never Before Exposed to Publick View,” and includes further recipes, an index of ailments, and treatises on the anatomy and function of the kidneys (“reins”), bladder, brain and nerves, and the spinal cord (“marrow of the back”). Most of his remedies seem unorthodox, though they would not have been unusual at the time. To cure hangover headaches, he suggests burning “Swallows in a crucible of feathers” and ingesting some of the ashes. To stop bleeding he advises one to hold toads, spiders, frogs, or their spawn in the palm of one’s hand so that the blood retires back into the body. To prevent gout, one is to mummify an owl and ingest its powdered remains, as a “bird of Luna should help a disease of Saturn.”

Culpeper was active during a period which saw attempts to overhaul the medical profession, at the time completely unregulated. In 1518, Henry VIII issued a charter which gave the Royal College of Physicians sole authority to issue licences and set professional standards. A century later, James I made a further attempt to regulate the practice, decreeing that all apothecaries in England were to obtain and consult a copy of the Pharmacopoeia Londonensis, a complete list of drugs and substances that physicians were legally able to concoct and distribute. Those who did not abide by the College’s terms were fined or imprisoned. Many medical practitioners had only a basic grasp of Latin, making it nearly impossible for them to consult the text. Furthermore, the text was predominantly a list of ingredients, ensuring that people remained beholden to a pre-approved list of physicians. Unlike his fellow pharmacists, Culpeper was university-educated, and in 1653 he translated the Pharmacopoeia into English under the title The London Dispensatory, much to the Royal College’s dismay. His subsequent medical texts were also made widely available and emphasised the use of herbs easily found in England. His book, The English Physician, or Complete Herbal (1652), is still in print.

ESTC notes the 1677 reissue has 18 unpaginated pages at the end comprising of 1 page of contents and 17 pages of advertisements, unlike the 1676 edition (Wing C7521A) which has 6 unpaginated pages. ESTC R227437; USTC 3091704; Wing C7521B. This ed. not in Wellcome, N.L.M., Osler, or Heirs of Hippocrates.