CHIROMANCY.

APPARENTLY UNPUBLISHED

Chiromantia universalis. Tractatus de manuum inspectione.

Italy, Manuscript on paper, C17£7,500.00

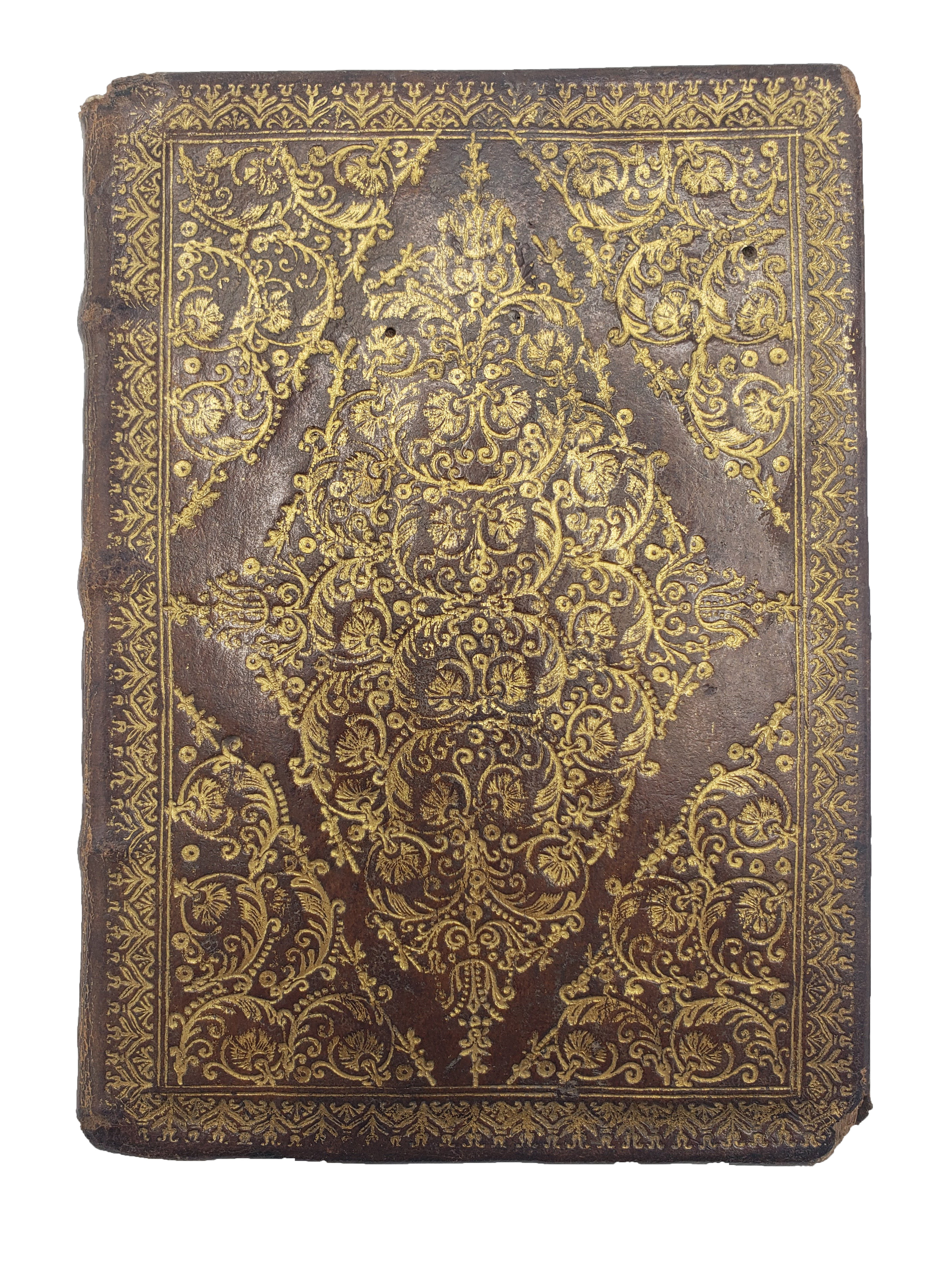

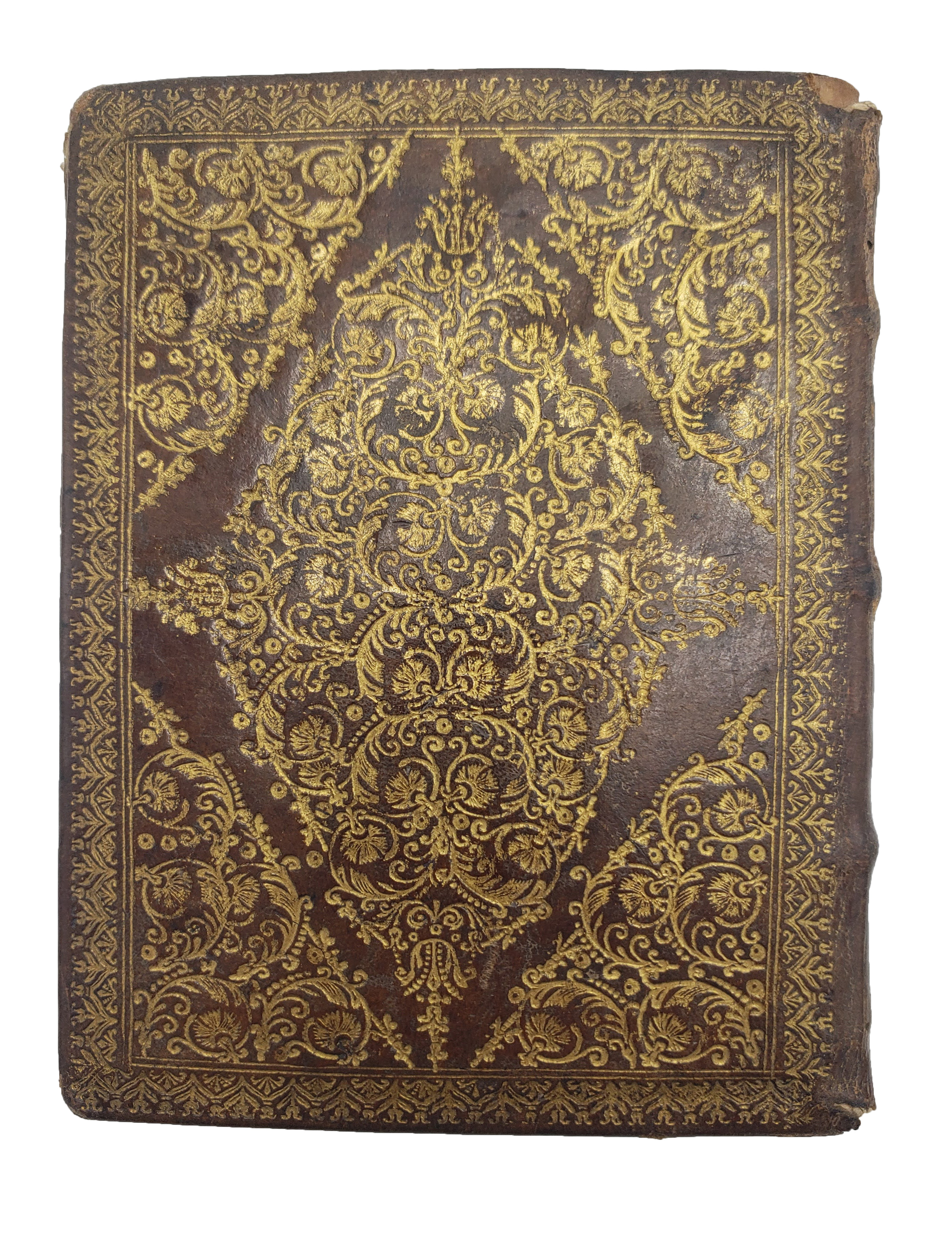

8vo. ll. (i) 25, final folding leaf with chiromantic diagram of hand, tear at blank fold. Rubricated ms. in a neat italic hand, page borders ruled in red. Attractive full page emblematical frontispiece drawing of a fool in motley, tail-piece of eight-pointed star. Very small wormtrack and wormhole to gutter of a few ll. at end, not affecting text. Margins occasionally slightly dusty, in very good condition. Contemp. Italian morocco elaborately gilt, panel of central diamond and four large cornerpieces made up of smaller arabesque tools, outer border of roll tool and double fillets, spine gilt in compartments, slight loss from head and foot of spine and at corners, one or two small wormholes, but generally very fine. C18 autographs to front and rear pastedowns, ‘Ex libris I.C.I. Gillard, Equier D.L.R. [i.e. ‘de la reine’] ex Grembergen,’ Belgium, earlier inscription erased from rear pastedown.

A fascinating, unique and unpublished manuscript treatise on chiromancy or the art or ‘science’ of palm-reading (as it is called in the first chapter), illustrated with a detailed chart of the hand noting the chief lines and regions of planetary influence. The treatise itself maps the different lines of the hand, dividing these into vital, cephalic, hepatic, etc. – the three main lines were thought to correspond to the heart, brain and liver – and then notes the prognostications that can be derived from their intersections and different features. These range from the predictable – a long line without intersections or points indicates a long life – to the alarming: an X-shaped cross on the hepatic line means that death is near. Otherwise the prognostications mostly concern character: choleric, faithful, bold, of good counsel and subtle intellect, etc. The author then considers the regions created by the intersection of lines, including the triangle, as well as a series of features of the hand’s ‘geographical,’ which corresponded with the planets: Cingulus Veneris, Via Solis, Monte Mercurii, etc., the ‘mountains’ being the bumps at the base of each digit. There is also a section on the signs of the planets, which are divided into benign and malign aspects, or felix and infelix. A benign Saturn portends skill in agriculture and metalwork, but is particularly bad when negative, promising various named illnesses such as catarrh and hydropsy, melancholia, misery, imprisonment, great peril to life, and death. The final chapter concerns the left hand, which is also the female hand, from which prognostications concerning women can be drawn: death in childbirth and stillbirths, but also freedom from romantic entanglements, etc.

The manuscript ends with a warning that nothing written in the book can have any power over the decree of Heaven, as well as a motto: ‘the wise man controls the stars.’ The amusing frontispiece, showing a fool carrying some kind of strainer – symbol of discernment and folly – chasing after a small flying devil and given the nonsense name ‘Strominisco Maggiore,’ meaning something like ‘The Great Confused One’ (from the Greek ‘strombos’ for confusion or disorder), is most likely a warning to the unlearned or duplicitous practitioner.

The first published chiromantic work appeared in 1504 by the astrologer Bartolomeo della Rocca or ‘Cocles,’ who was murdered by someone whose violent death he had predicted in print, correctly as it turned out (Thorndike V, 50-68). The practise was frequently criticised or prohibited by the Catholic Church, not least in the Index of 1564, but large numbers of printed works on chiromancy continued to appear into the C17th. This manuscript appears neither to have been the basis for any published work on chiromancy, nor was it copied from any printed work. Neither the title, subtitle, nor the distinctive nonsense phrase above appear anywhere in library catalogues or bibliographies (see Thorndike V, Appendix 2, 673-678).

The previous owner, Jean-Joseph Gillard de Champnouveau or Van Nieuwvelde (c.1730-1803), is listed in sources as having been a medical doctor, though we have been unable to trace any details of his library.