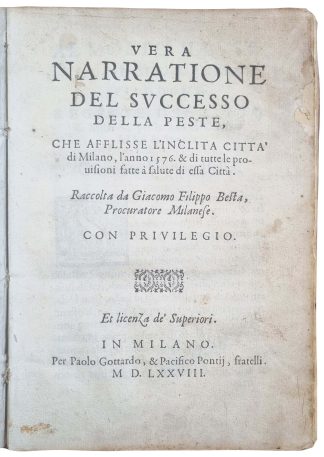

BESTA, Giacomo Filippo.

EPIDEMIC ‘DISASTER’ MANAGEMENT

Vera Narratione del successo della peste che afflisse l’inclita città di Milano, l’anno 1576.

Milano, Paolo Gottardo and Pacifico Ponti, 1578.£2,500.00

FIRST EDITION. 4to. ff. 56, [12]. Italic letter, little Roman. Typographic ornament to title, decorated initials. Title dusty, small loss to fore-edge, strengthened on blank verso, light age yellowing, very small water stain to fore-edge of initial gatherings, occasional slight finger-soiling, the odd ink splash or mark, last gathering loosening but sound. A very good copy in contemporary vellum, traces of ties, small loss to spine, slightly creased, ms ‘1720 22 8bre Gio[vanni] Gussone’ and ms numbers to front pastedown, a few early C20 ms marginalia and old red crayon underlining to text, note at foot of last text page identifying the former as the chaplain at the Hospital of St Ambrose, in Milan, 1834 ms acquisition note and few others to rear pastedown.

A very good copy of the first edition of this detailed account of the plague that hit Milan in 1576 – a wonderful early witness to disaster management – with, appended at rear, a collection of poems on the same subject. Giacomo Filippo Besta, of whom little is known, was a notary and gate guard during the plague of 1576. His account ‘attributed far more to the secular arm of the state than to Cardinal Borromeo’s spiritual and secular initiatives, and examined in greater detail and with more documentation events within the city walls as well as showing greater concern for the plague’s spread within Lombardy. [It] devoted attention to the communication between the various city-states and Milan and compared Milan’s reactions and solutions with measures taken in Verona and Venice’ (Cohn, p.106). The account begins with Besta’s hypothesis on the contagion: the plague was supposedly brought from Trento in 1575, despite the use of city guards (whose names are listed) and ‘health passes’ (‘bollette’) in Milan. There follows an account of the early stages, with the identification of potential ‘patients zero’ – i.e., people who were clearly ill but managed to escape isolation – as well as the decision to ‘lock down’ inns and stop all commercial activities involving gatherings for over a year. Besta traces the spread of the plague within Milan, and provides incredibly detailed descriptions of processions and ceremonies made to protect the city, various strategies to manage the sick (e.g., the issuing of health passes to people who were somehow immune from or had overcome the plague), the expenses incurred by the community (e.g., for French doctors called to assist), the management of alms, medical remedies, burials, food and last wills for an extensive number of dying people. At the end, Besta marvels at the ‘many means and ways in which money was sought and obtained by city officials to assist the needy’, with an eye-watering total expenditure of a million five hundred and seven thousand lire, which he hoped the King of Spain would partly refund. The appended poems, written by Giacomo Filippo Giardini and Lodovico Gandini, sing the tragedy of the plague, the mass death of people of all sexes and ages caused by this ‘invisible war’, by the ‘cruel monster who infects human bodies with deadly poison’, the miserable carts transporting bodies, and the dreaded symptoms. An immensely interesting book for the history of epidemic disaster management.

USTC 814306; EDIT16 5653; Durling 568 (imperf.); Wellcome I, 6842 (marked ‘missing’). Not in Heirs of Hippocrates or Osler. S.K. Cohn, Cultures of Plague (2009).In stock