ARETINO, Pietro

BOUND FOR CHARLES DE VALOIS

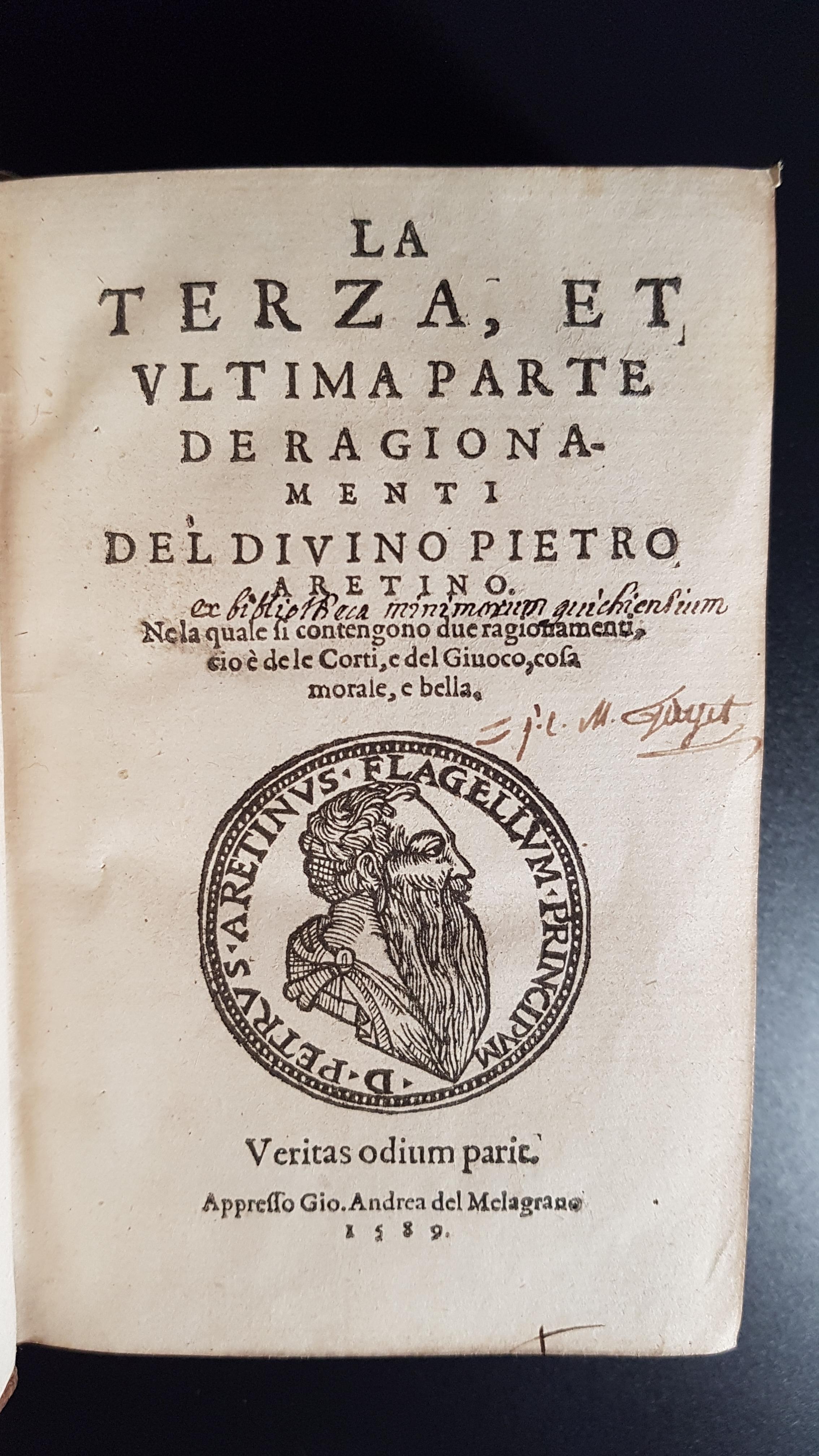

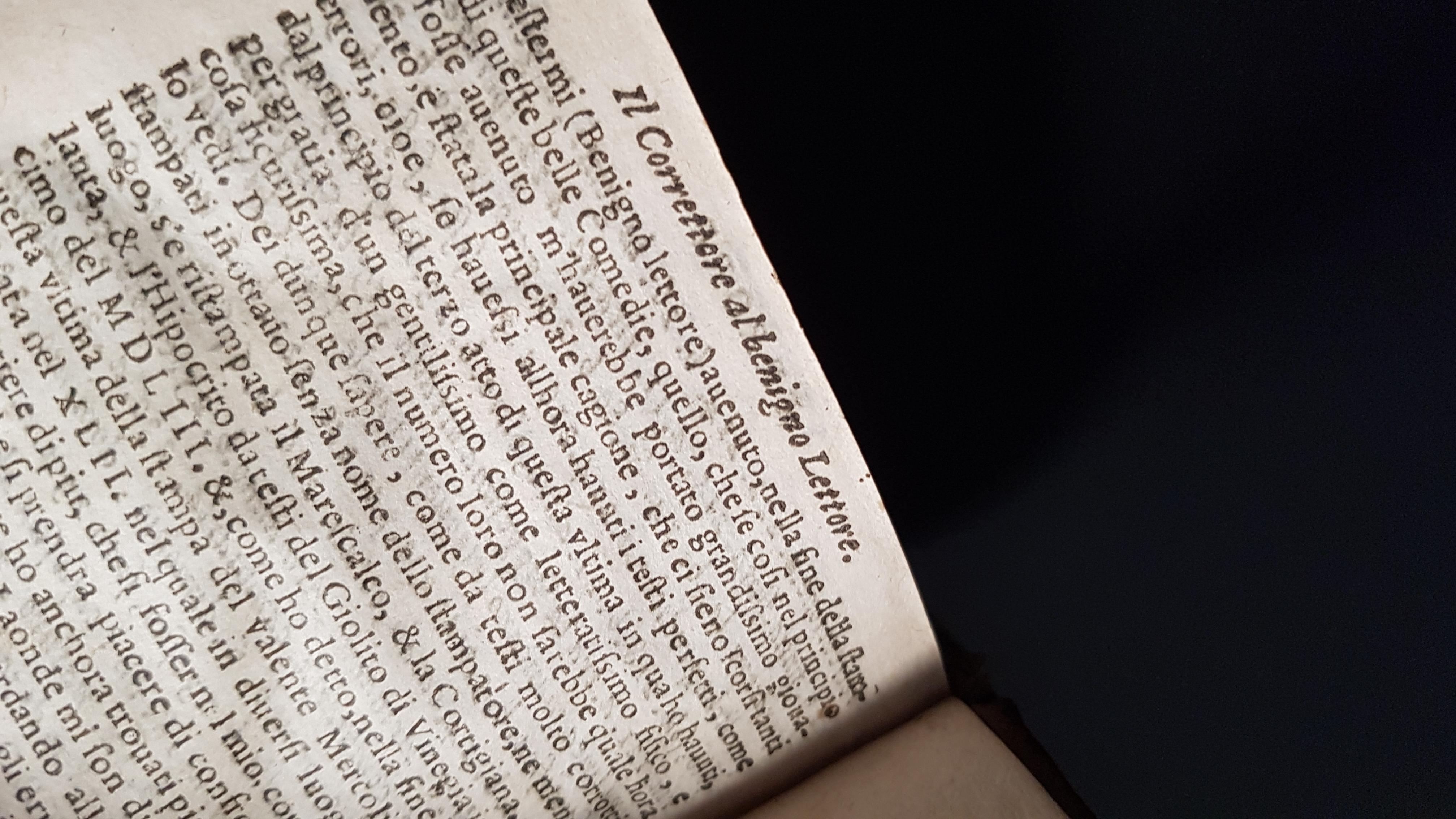

La terza, et vltima parte de Ragionamenti del diuino Pietro Aretino [with] (2) Quattro comedie del diuino Pietro Aretino. Cioè Il Marescalco La cortegiana La Talanta, L’hipocrito.

(1) [London], Appresso Gio. Andrea del Melagrano [i.e. John Wolfe], 1589, (2) [ printed by John Wolfe], [1588]£10,500.00

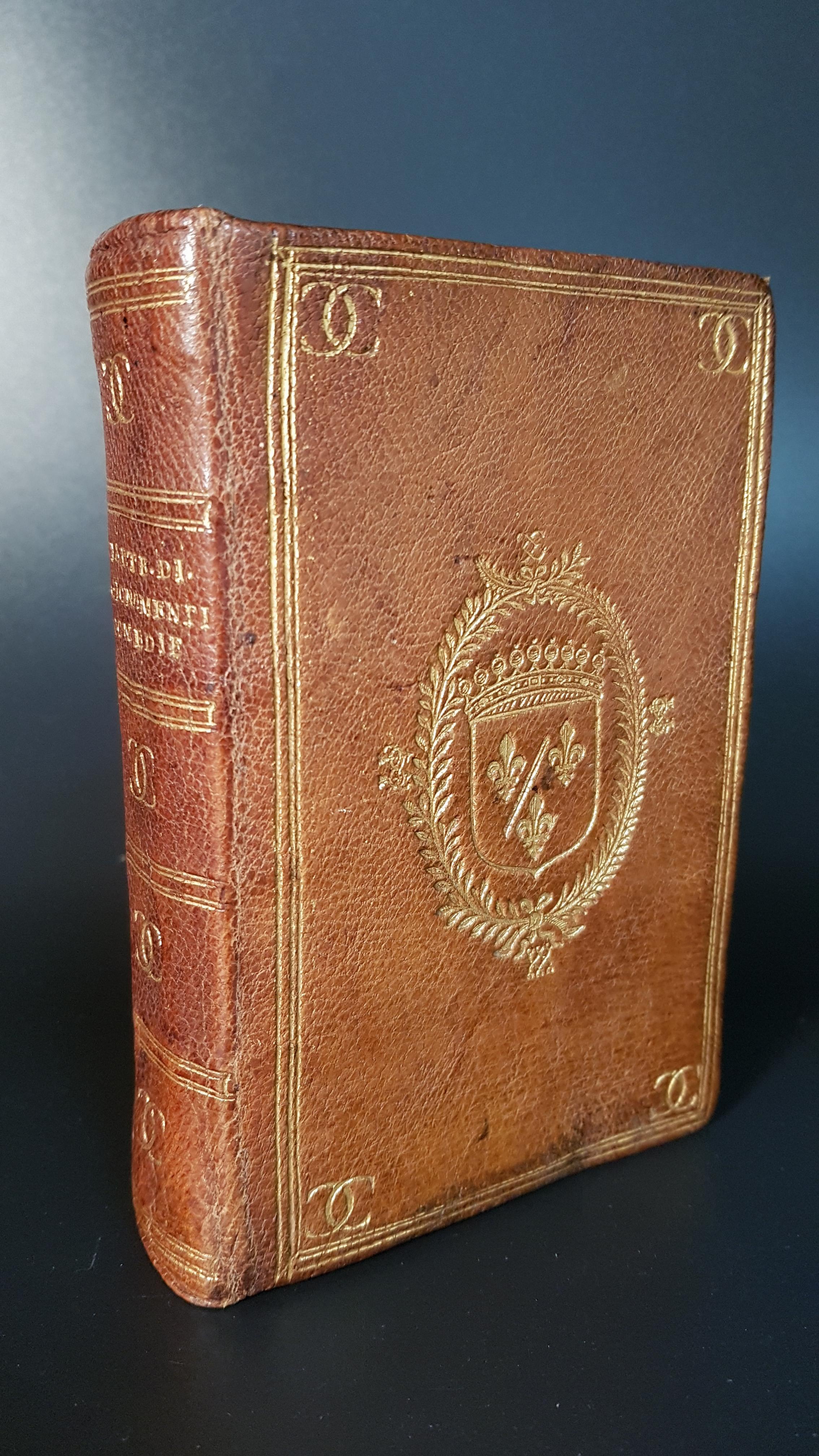

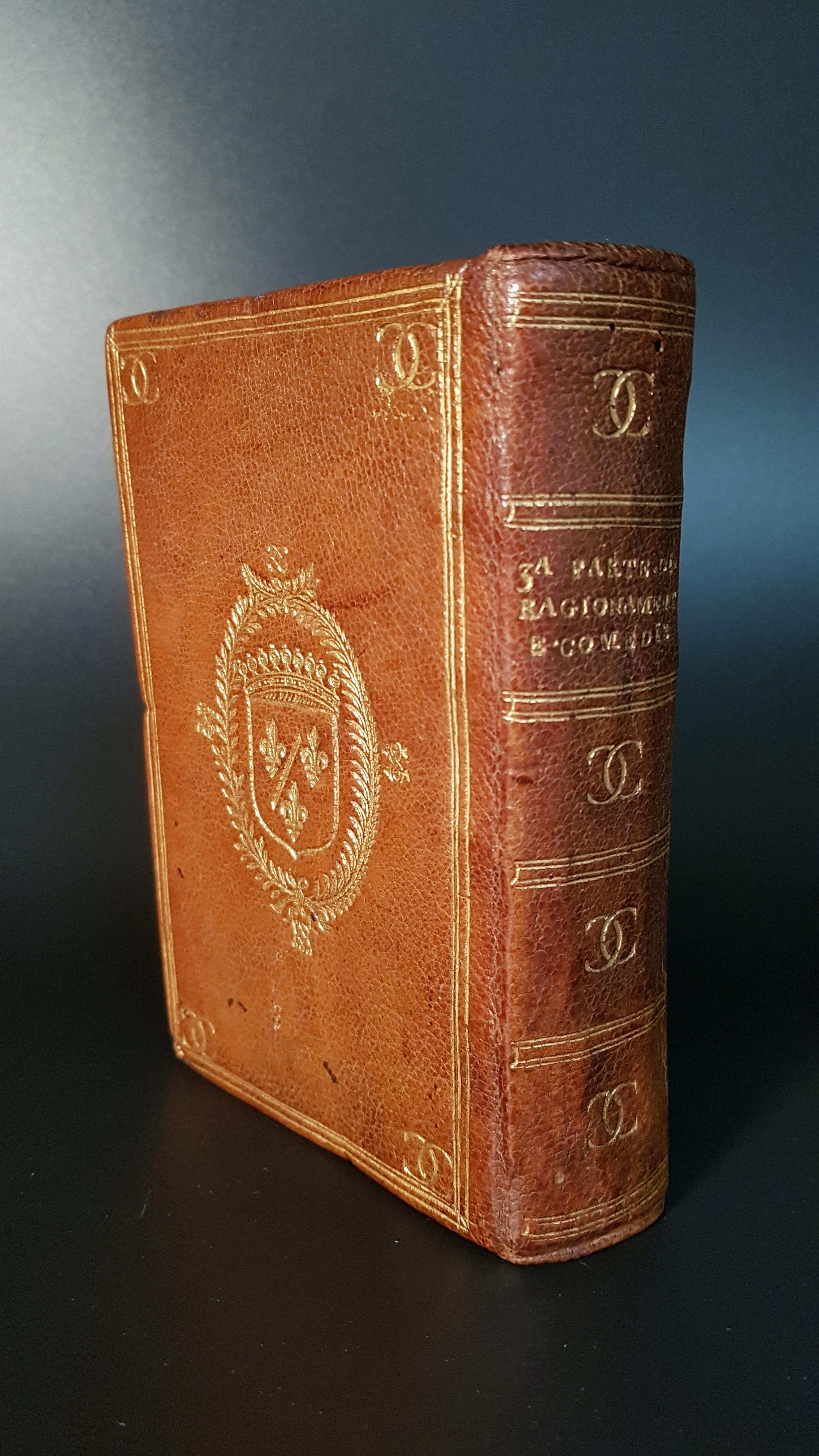

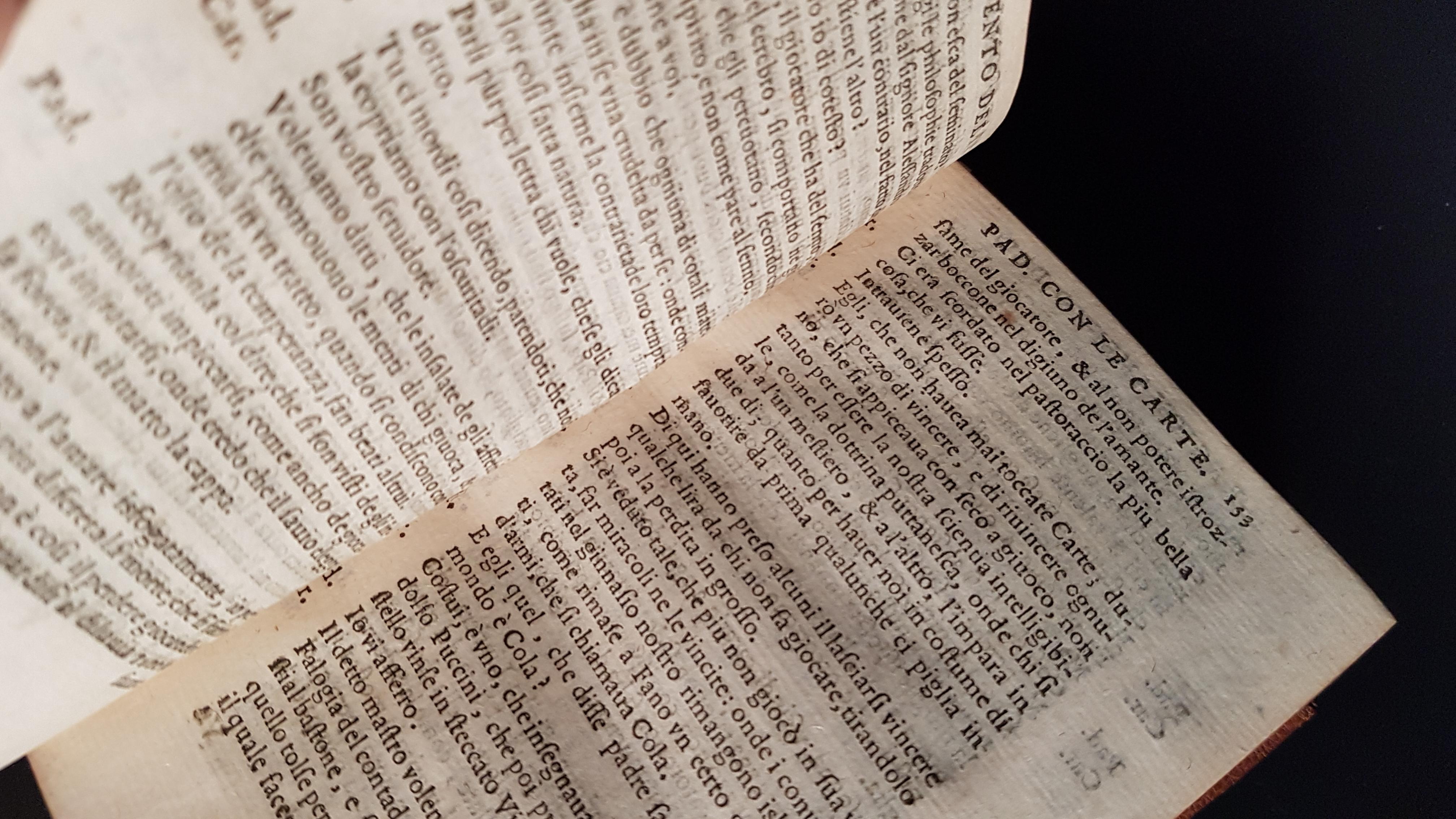

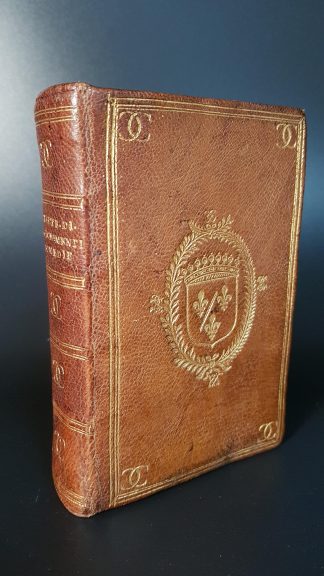

8vo. Two vols in one. 1) ff.[iv], 202, [ii]; [* , A-2B , 2C ]. 2) ff. [viii], 285, [iii]. [A-2O .] “La cortigiana”, “La Talanta”, and “L’hipocrito” each have separate dated title page; pagination and register are continuous. Roman letter, some Italic. Woodcut roundel portrait of Aretino on titles of each part, small woodcut initials and headpieces, engraved bookplate of Maurice Burrus on pastedown, early autograph ‘Fayet?’ on t-p. Light age yellowing. A fine copy, crisp and exceptionally clean, in stunning contemporary tan morocco gilt, covers bordered with a triple gilt rule, ams of Charles de Valois gilt at centres within olive branch wreath, small fleurons to sides above and below, monogram of interlacing double Cs gilt to outer corners, spine double gilt ruled in compartments monogram of double Cs gilt at centres, title gilt lettered, a.e.g. spine fractionally darkened, in a red morocco box.

A very lovely copy, beautifully bound for Charles de Valois, the son of King Charles IX of France, of these rare editions of Aretino printed clandestinely by John Wolfe in London. These English editions of Aretino’s work, particularly the comedies, pose the question as to whether Shakespeare had read Aretino in this form. “All of the four comedies provide significant cues for Shakespeare’s plays especially for the plot construction of such works as the Taming of the Shrew, the Comedy of Errors, and Twelfth Night, where we find some unique solutions in the comedic structure which were anticipated by Aretino’s innovative theatre.” Michele Marrapodi. ‘Shakespeare and the Italian Renaissance:.’ It is certain that Arteino was of great influence on other contemporary English writers who borrowed heavily from his works, particularly Jonson and Middleton. “One of the more versatile and prolific writers in the Italian vernacular, Peter Aretino made a significant impact on the literary, political, social, and artistic world of 16th century Italy. .. At the court of Rome, Aretino developed his skill at political and clerical gossip in the form of pasquinades and lampoons. During his stay there, Aretino also drafted La Cortigiana (The Courtesan) in which he satirized the papal court and Baldesar Castiglione’s manual for courtly behaviour, Il Cortegiano (the Courtier). While Aretino is frequently described as an anti-classical, anti-humanistic, and scurrilous author who proudly posted of never having studied Latin, La Cortigiana reveals a rich heritage of sources, includingVirgil, and Erasmus, and the contemporary humanistic treatise…. In 1534 Aretino published the first part of I Ragionamenti, a series of dialogues in which prostitutes vividly discuss their profession. Like many of his other works, this play interweaves literary and historical plots with a satirical target as it parodies the literary form of the dialogue and Neoplatonic theories then in vogue as embodied in Pietro Bembo’s ‘Gli Asolani’. Jo Eldridge Carney ‘Renaissance and Reformation, 1500-1620: A Biographical Dictionary.’

“The printer John Wolfe worked for some years in Florence, and was active in London between 1579 and 1601. In the early1580’s he decided to print, though surreptitiously, Machiavelli’s two most controversial works as well as Aretino’s Ragionamenti in Italian. His work did not have an outright clandestine nature, but by inserting fictitious Italian cities as places of publication on the frontispiece he was able to avoid the control of the Stationers’ Company… In practice, Wolfe was printing for three different categories of readers. English people who could read Italian; the Italian community in England; and the foreign market. Evidence of the latter is offered by his involvement in the Frankfurt book fair in which books in the English language were not normally present; the two former categories indicate an intellectual elite.” Giuliana Iannaccaro. ‘Enforcing and Eluding Censorship: British and Anglo-Italian Perspectives.’ “by printing in foreign vernaculars, and using a fictitious imprint, (Wolfe) could evade the restrictions imposed on…his business by the monopolist printers…Wolfe became the recognized leader of the whole movement against privileges” Woodfield, ‘Surreptitious Printing in England’. Another reason for his surreptitious printing was to circumvent the new papal Index which limited what could be printed by Italian firms

Charles de Valois d’Angouleme, (1573 – 1650) was the illegitimate son of Charles IX, king of France, and Marie Touchet. He was born at the Château de Fayet in Dauphiné in 1573. His father, dying in the following year, commended him to the care of his younger brother and successor, Henry III who faithfully fulfilled the charge, commending him in turn, on his deathbed, to Henry IV of France. He fought for Henry IV, then for Louis XIII at the siege of La Rochelle and in the wars of Languedoc, Germany and Flanders. His library, particularly rich in Italian and Spanish works, was bequeathed by his eldest son, Louis de Valois, Count of Alais, to the Monastery of Guiche, in the Charolais and was dispersed during the Revolution.

A beautiful, exceptionally preserved copy, of these rare and important editions of Aretino.

1) ESTC S114907 STC 19913. BM. STC. It. p. 518. Adams A 1582. Index Aurel. 107.121. Woodfield, ‘Surreptitious Printing’ no. 48. 2) ESTC S120618. STC 19911. BM. STC. It. p. 517. Adams 1562. Index Aurel. 107.120. Woodfield no. 43.In stock