Admonitiones ad consolationem infirmorum, with Ordo commendationis animae and Flores Augustini.

11th CENTURY, UNRECORDED

Decorated manuscripts on vellum.

Germany, probably Hildesheim, Lower Saxony, (i) late eleventh century, (ii) fifteenth and (iii) thirteenth century£125,000.00

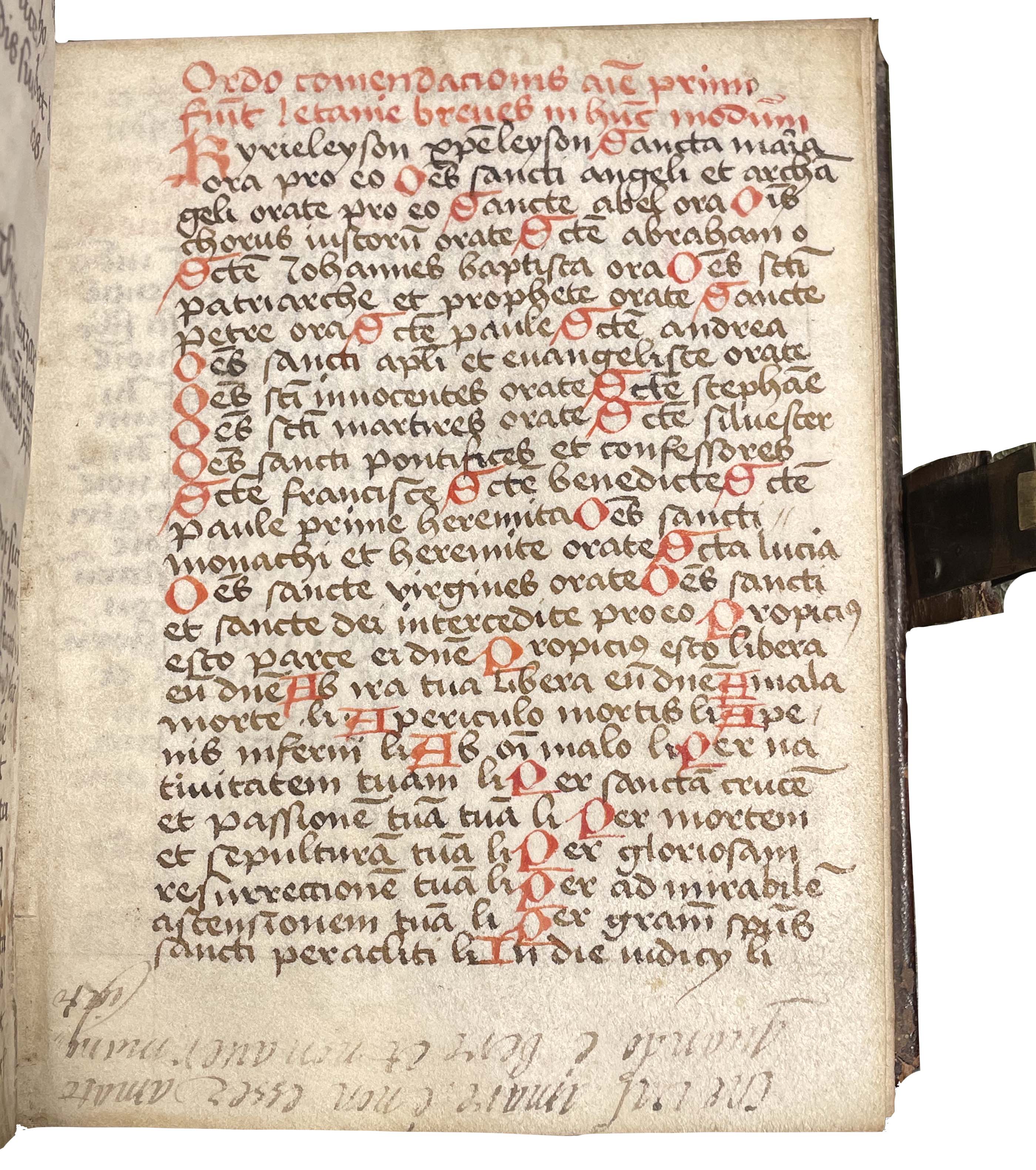

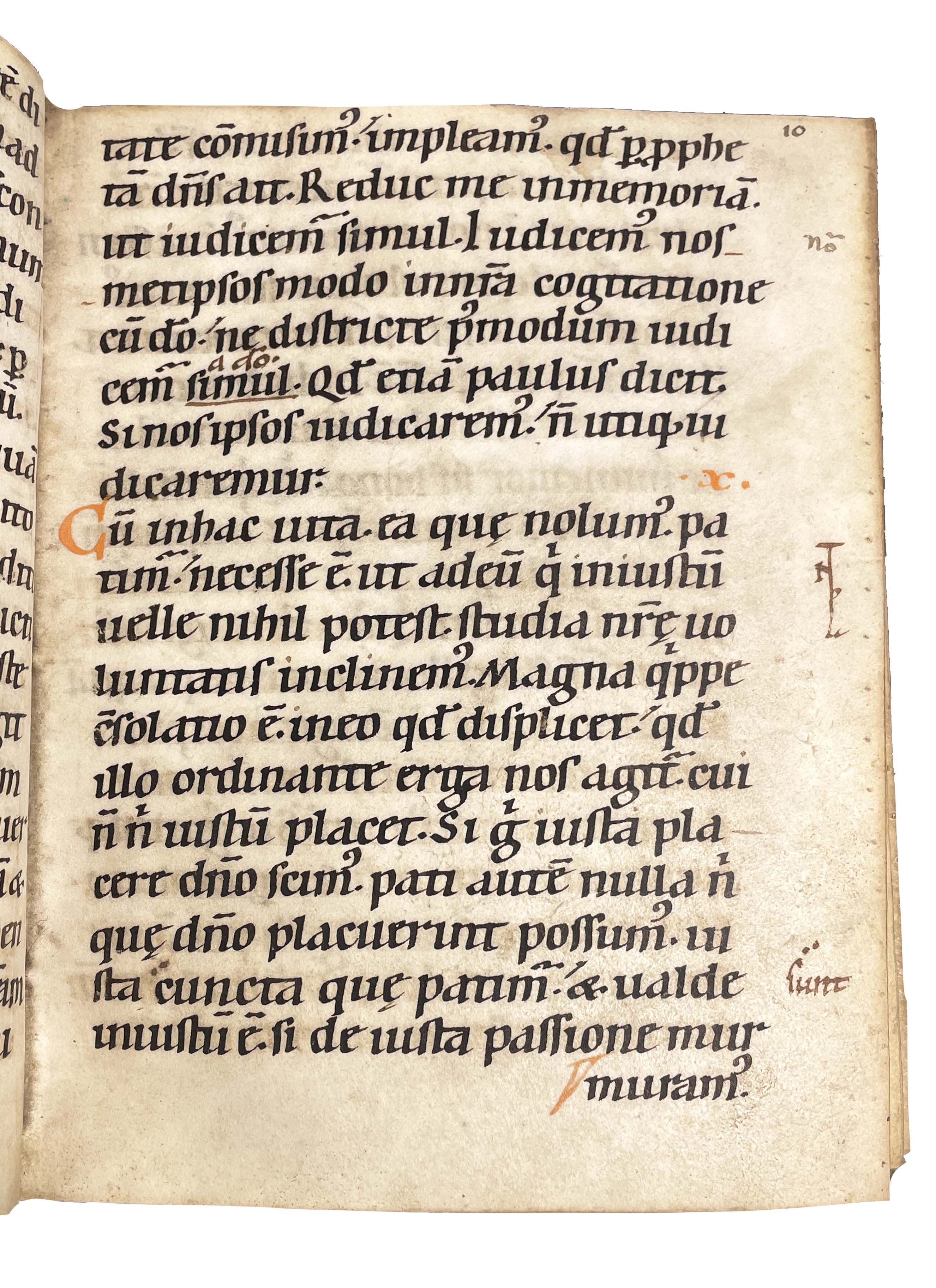

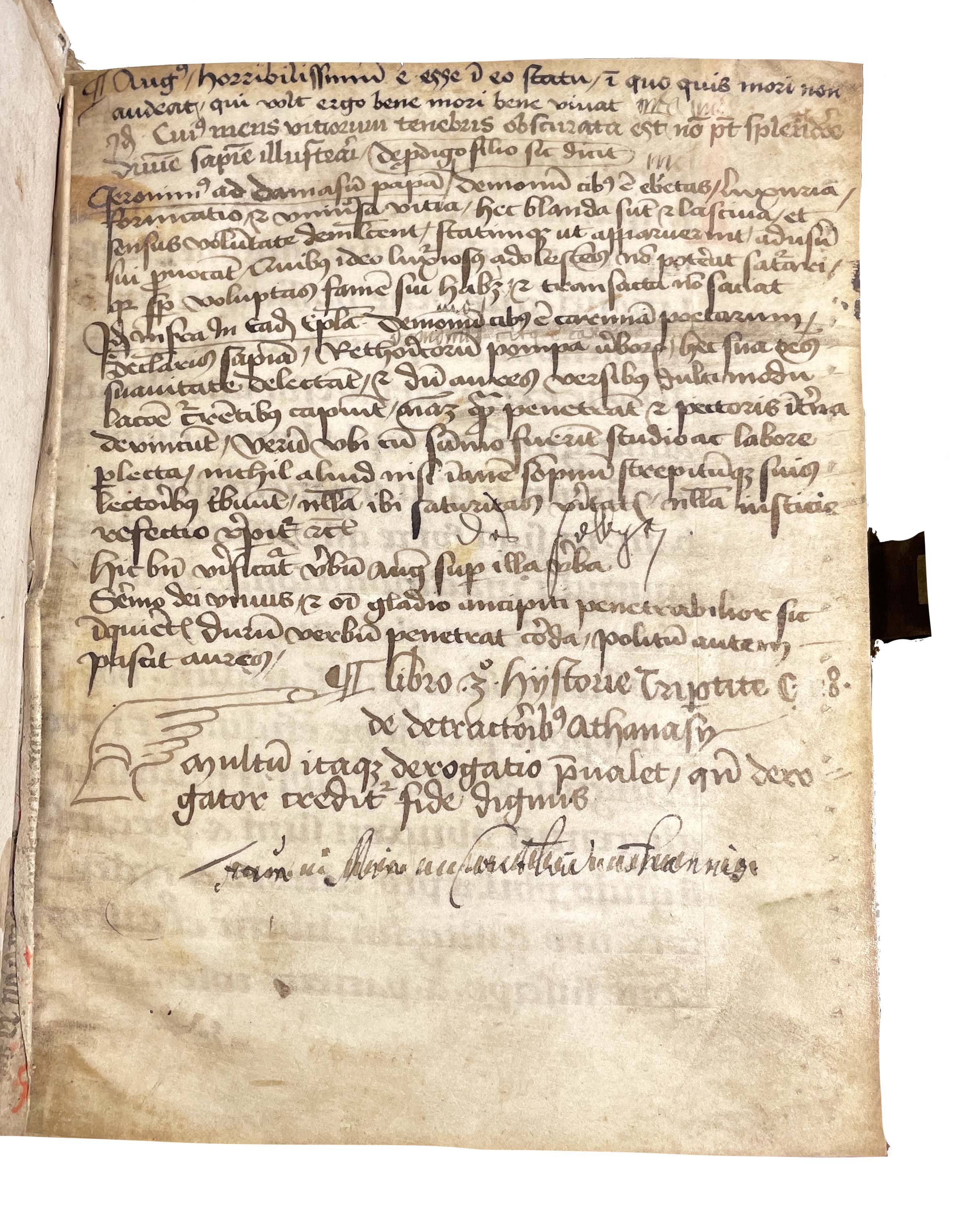

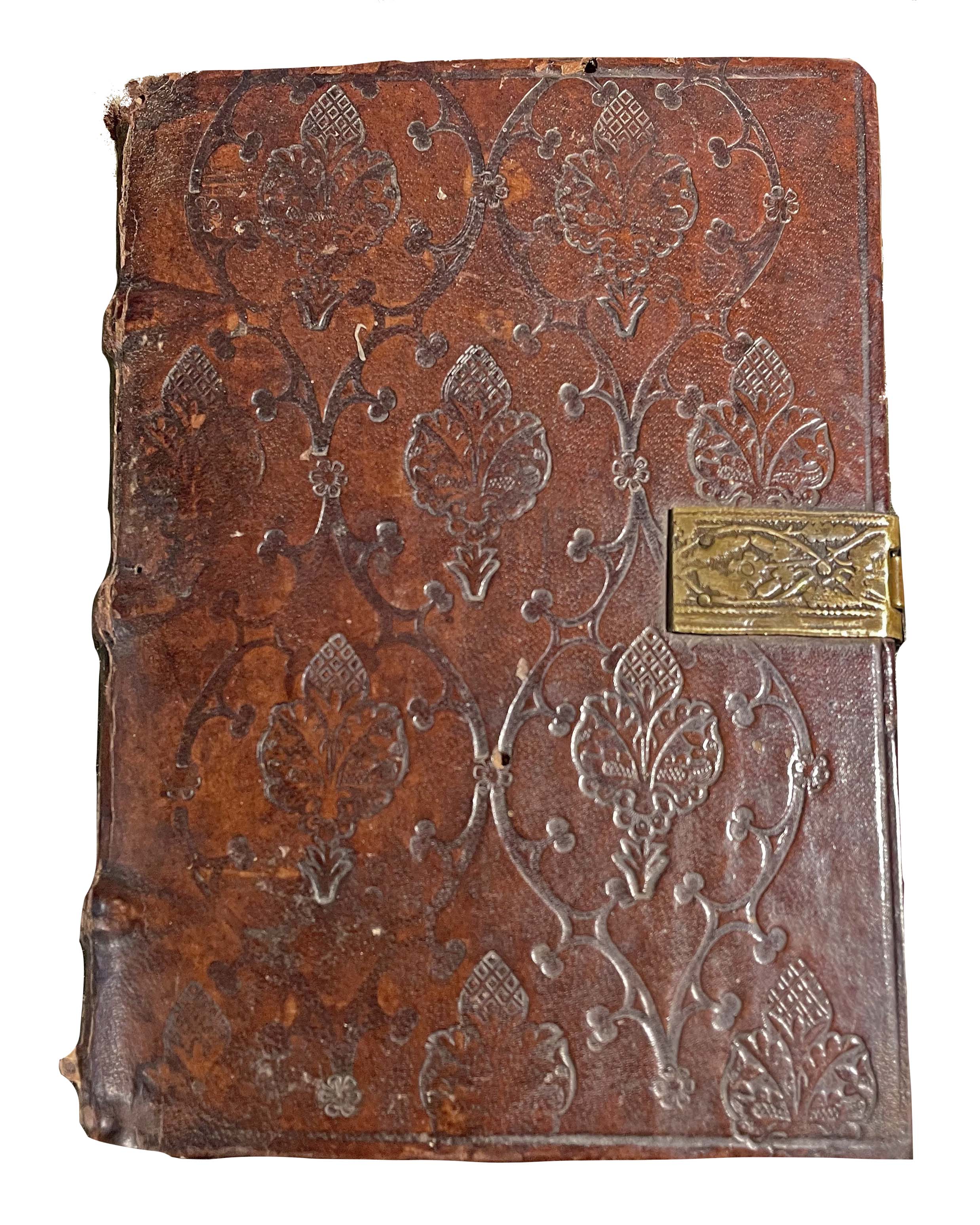

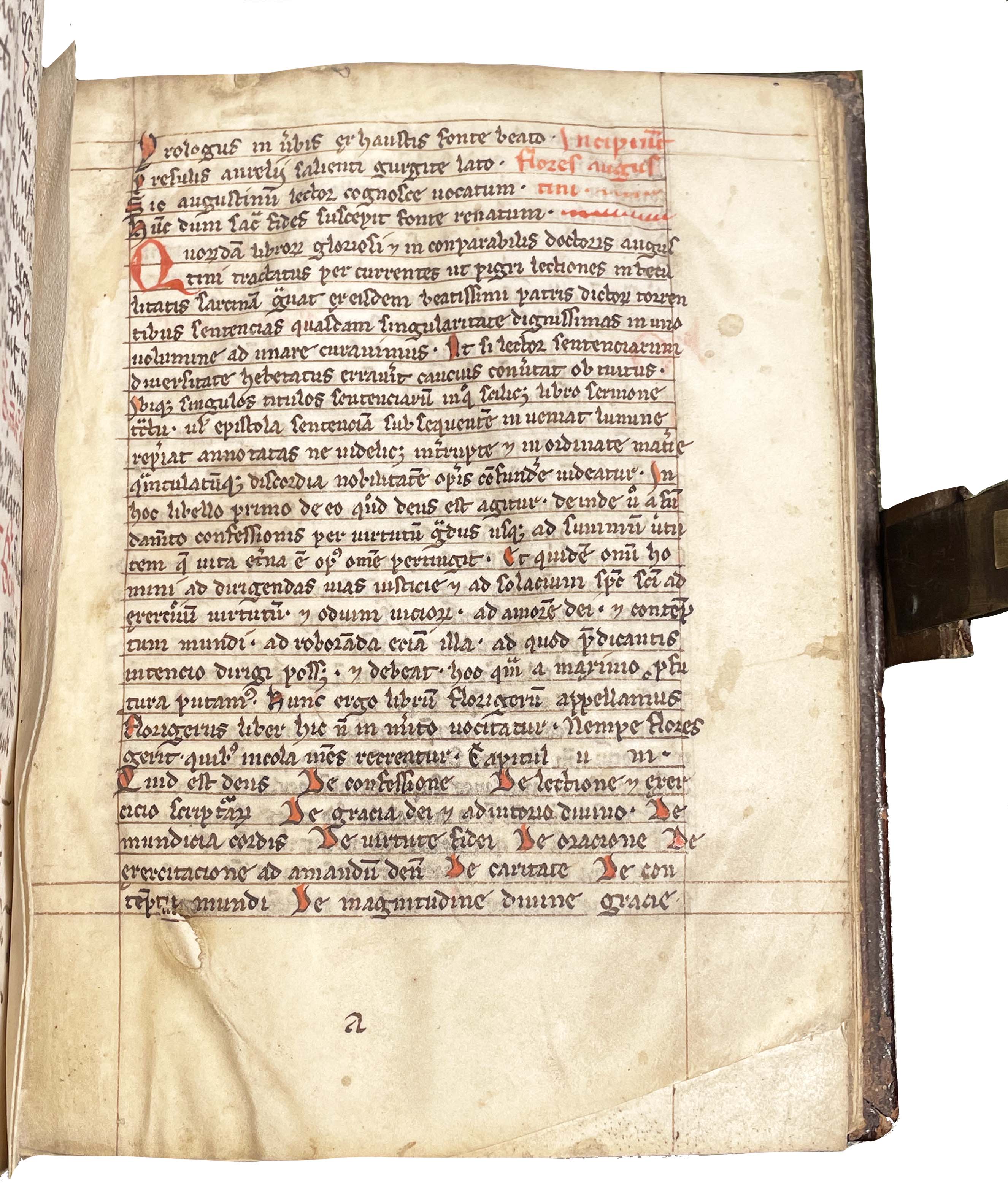

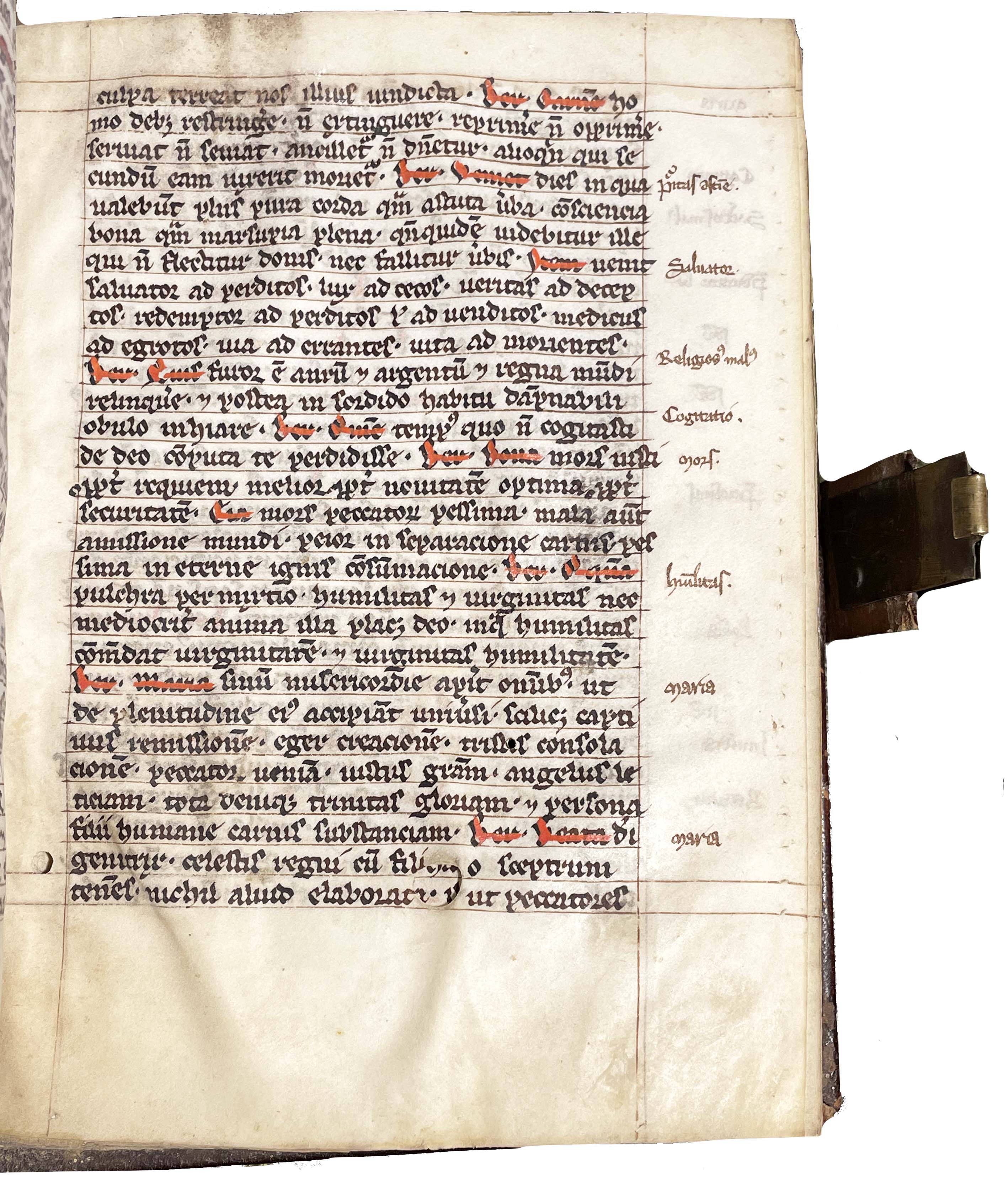

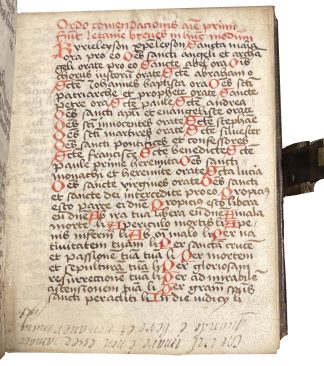

Small 4to. 160x120mm. (i) 93 + 1 ll. complete. (ii) 4ll. (iii) 48ll., complete, likely late eleventh century, (plus fifteenth-century paper endleaves at front and back), original Romanesque book, collation: (i) i-xi8, xii6 (last 2 leaves blank cancels), (ii) xiii4 (probably very early fifteenth century; last 2 leaves cut away), (iii) xiv-xvii8, xviii6, xix10, (thirteenth century). Original Romanesque leaves (c.1080) single column, 19 lines per page in a square and squat German Romanesque hand, rubrics and large initials in orange-red, capitals touched in same colour. Second work fourteenth/fifteenth century in single column of 25/26 lines per page with pale red rubrics and capitals, last text thirteenth century, single column of 29 lines with rubrics in bright red and capitals in same, underlining in red through middle of crucial words in keeping with medieval practice. Fourteenth- or perhaps early fifteenth-century binding fragments from a liturgical manual citing Ecclesiastes visible where book block meets the back board, trimmed at edges (more noticeably with the original Romanesque leaves) but text unharmed. A few spots and light stains, generally very good, in mid fifteenth-century tooled leather over heavy wooden boards (tooled with floral compartments enclosing sprigs of thistle-like foliage on front board and eagles and flower heads on back), sewn on three large double-thongs, single working clasp with brass fittings at horizontal edge, some chips and bumps, but a remarkable manuscript sammelband, in box. In folding cloth box.

Provenance, and the stages of construction of this volume:

- The main part of this codex was written and decorated in Germany before 1100, most probably in a monastery for the use of the monks. This section (here fols. 1-94) was once a discrete codex of its own containing a single text (see below), and has early foliation added perhaps in the fourteenth or fifteenth century, that does not continue into the remainder of the volume.

- In the later Middle Ages, most probably the fifteenth century, that Romanesque codex had two smaller codices combined with it and the three were bound together in the present fifteenth-century binding. At the same time, notes on medical recipes were added to previously blank space at the end of the first work and to the pastedowns, while a series of readings from Church Patriarchs was added to an endleaf at the front of the book.

- This sammelband received two ms ex libris inscriptions at the foot of its first original endleaf in the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century. The first begins with the name “Johanni” (announcing the book was then in use or owned by someone named Johannes), but irritatingly, the second of these inscriptions is scrawled, highly abbreviated and was written on top of the first, mostly obscuring the earlier one and making it very hard to decipher. The later inscription appears to read “Fr[at]r[u]m Min[orum] Carthu’ Frannci” (with the first two words uncertain). The first three words here probably identify the house that owned the book as the Franciscans of Hildesheim (Carthusia = Hildesheim), and the last an attempt to abbreviate ‘Francisci’ (‘of St. Francis’). The Franciscan convent of Hildesheim was established in 1234 as part of the earliest push of the movement into Saxony and its neighbouring regions, and so the earliest parts of the present book may have been among the books donated to the community on their foundation. The church of the community was built around 1250, and converted to a parish church on the suppression of the monasteries in the town during the Reformation. S. Krämer lists only fifteen manuscripts from the house surviving in the archives and town library of Hildesheim, all of the fourteenth century or later (Handschriftenerbe des Deutschen Mittelalters, 1989, I, p. 356), and about the same number have passed through the trade, by Ludwig Rosenthal cat. 120 (1909), no. 68, Georges Andrieux in 1930 from the collection of the Baron de Gruneisen, Quaritch, cat. 699 (1952), no. 133, and the same again in cat. 742 (1955), no. 23, and cat. 775 (1958), no. 800; and most recently Jörn Günther, list 5 (1997), no. 3 and Sotheby’s, 17 June 2006 (Ritman III), lot 28. Other codices are in the Herzog August Bibliothek (two codices), the Royal Observatory in Edinburgh, Ampleforth Abbey, Stonyhurst College, the Houghton Library in Harvard and Saint Vincent Archabbey in Pennsylvania. Of these listed here, only those in the Herzog August library date before the fourteenth century, with only one of those (from the mid-twelfth century) having any claim to be Romanesque.

- Johan Jacob Silberman 1683, with his ex libris on front endleaf.

- Apparently in Italian hands in eighteenth century, with short inscriptions of this date, added to the borders of fols. 74r and 94r.

- Re-emerging recently in France, and granted a permanent export license by that country.

Text:

The original Romanesque codex comprises a single text that the main copyist and the scribe of the brief contents list in the upper outer corner of the front pastedown call ‘ad consolationem infirmorum 4 libri’ and ‘Admonitiones ad consolationem infirmorum’. It comprises a large compilation of quotations from the works of the Church Fathers and other early Christian texts for recitation and consolation to the infirm and sick, opening with a long quotation from Gregory the Great’s Cura Pastoralis, and substantial readings from Alcuin’s homilies, the vita of St. Pachomius, the vita of St. Stephanus monachi by Heraclides Paradisus, Isidore of Seville’s Sententiarum and many from the Vitae Patrum. An earlier, attribution of this compilation to Pope Gregory the Great is erroneous, and is a misinterpretation of the fact that Gregory’s name follows immediately after the incipit of the main text and at the head of the first quotation – but as the author of the latter, not the whole compilation. It has defied identification, and may well be the sole recorded witness to this text. It is not the Liber Scintillarum or any of the other such compilations known to us, and the author’s prologue here, opening “In hoc libello ad consolationem infirmorum ex sententiis & exemplis …” and ending “…preparare studeat ut beato fine de hoc mundo transire mereatur”, is not traceable in either Patrologia Latina or the vast In principio database (now up to one million entries). It is clearly deserving of much further study.

That codex received additions in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries on its originally blank endleaves of complimentary material, including an early witness to the spoken charm against epilepsy: “Caspar fert mirram thus Balthazar Melchior aurem, Hec tria qui secum portabit nomina regum, Solvitur a morbo Christi pietate caduco” on fol. 90v, widely witnessed in manuscript contexts and a finger ring in the Franks bequest in the British Museum (AF.1017).

To this was added in the early fifteenth century the short four-leaf liturgical text titled the Ordo commendationis animae (‘Order for the committal of souls’, ie. extreme unction), in the same hand as the last additions to the endleaves of the earlier codex, as well as a previously separate booklet (of 48 leaves) of the thirteenth century containing the Flores Augustini, a popular anthology of thematically arranged quotations from the works of St. Augustine and then St. Bernard of Clairvaux. The whole was then united with the addition of the brief contents list to the front pastedown, and further additions made to blank space in the volume or on its endleaves, usually of a medical-exhortational nature.

Script:

The script here is typically German in its square and squat aspect, and fits into a group of Germanic bookhands produced at the end of the eleventh and opening of the twelfth century. A close parallel can be found in a Glossed Psalter now in Cologne Cathedral and dating to the 990s (see Glaube und Wissen im Mittelalter, 1998, no. 40: Dom. Hs. 45).