A RARITY OF IRISH LANGUAGE PRINTING

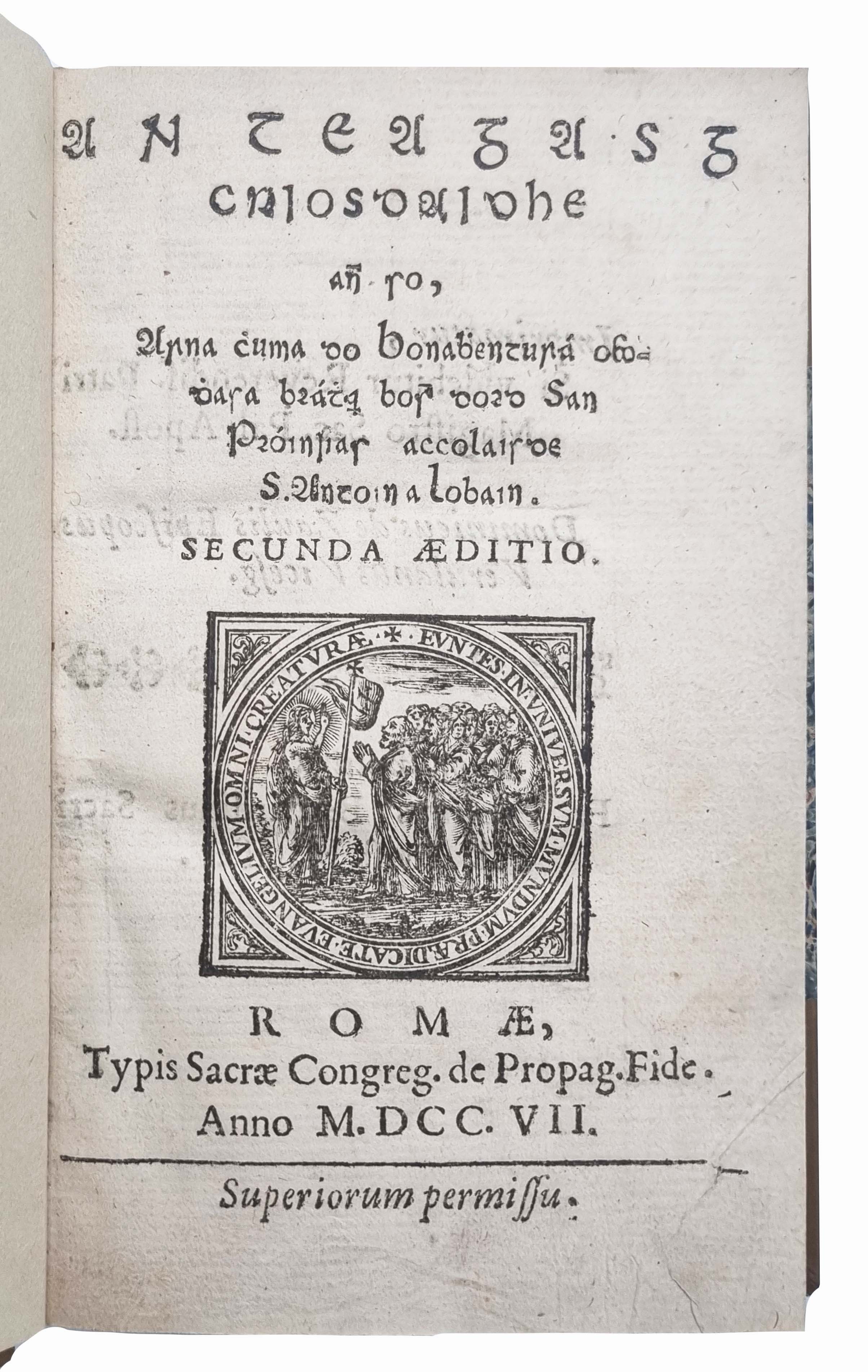

An teagasg Criosdaidhe...

Rome, Typis Sacrae Congreg. de Propag. Fide, 1707£2,750.00

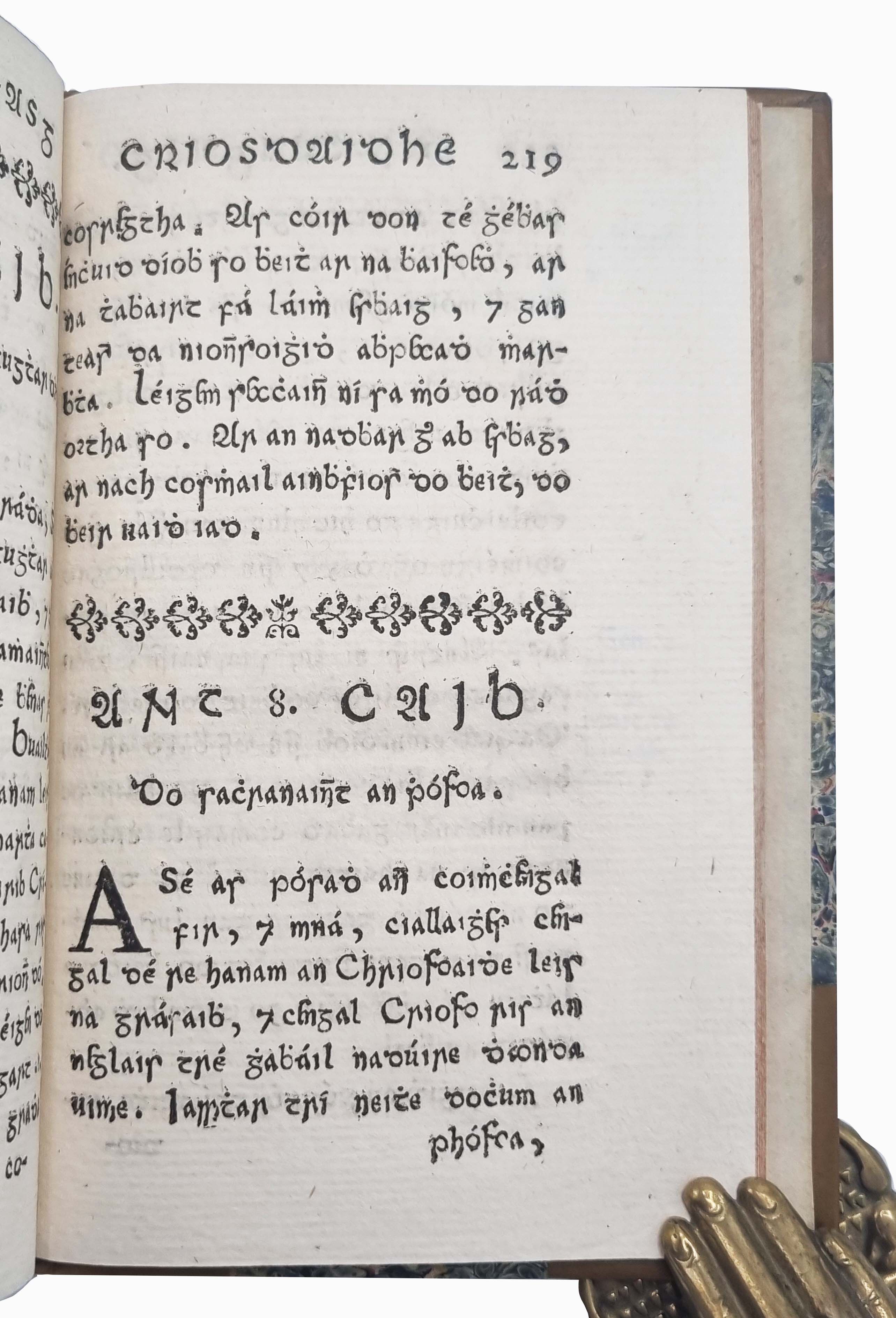

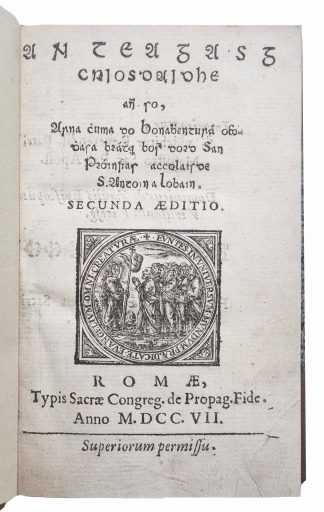

8vo. pp. 259 [i.e., 256], [8]. Gaelic letter, occasional Roman. Woodcut printer’s device to title, full-page woodcuts of the Crucifixion and the Virgin of Loreto to a1 recto and verso, decorated initials and ornaments. Intermittent light age yellowing. A very good, clean copy in modern half calf over marbled boards, gilt-lettered label.

An excellent copy of the third edition of the Irish Catechism of Giolla Brighde O’Heoghusa (Bonaventura O’Hussey or Eodhusa, 1574-1614) – ‘the material incarnation of the complex and fascinating history of Irish character types’ (Ferlier). The first and second eds of 1608 and anytime between 1611 and 1616 (undated) – all by the Irish Franciscan Press in Leuven – survive together in less than 10 copies. Whilst the titlepage calls this edition ‘the second’, this should be considered the third, printed with Irish type commissioned by the Propaganda Fide in 1675, in use until 1707 (Lynam, p.11).

O’Heoghusa was an Irish Franciscan and poet from Ulster, based at the Irish college in Leuven. ‘The publication of “An Teagasg Critosdaidhe” in Antwerp […] marked a watershed in the history of Irish exiles in the seventeenth century. It was not only a catechism in the Tridentine mould but also the work of an individual’ (Ryan, p.259). It was also ‘the first legitimate printed Irish letter’ (Lynam). The 1707 ed. was revised by Philip McGuire, at the Irish College of St Isidore, in Rome. The establishment of European colleges for the training of Irish missionaries after the Council of Trent was intended to circumvent the Protestant hold on Ireland, and led to an increase and honing of Irish printing. Whilst broadly following the Tridentine ‘Roman Catechism’, ‘Teagasg’ is not just a translation. It differs ‘especially in its tendency to address issues peculiar to the land for which is was composed’, thus resembling ‘catechisms produced for use in mission territories’, such as that for the Hurons in French Canada (Ryan, p.264). The intended audience were Irish priests, soldiers, and the educated laity. O’Hussey’s addition of verse summaries of doctrinal principles made his work extremely popular, thanks to his poetic skills; the summaries themselves were widely circulated in ms. The final gathering, introduced by two woodcuts, comprises O’Hussey’s Irish poem ‘Tosach agus aistriugha miorbhuileach Theampoill Mhuire Loreto’, on the miraculous translation of the shrine of Loreto. ‘Eodhusa’s success in strategically placing bardic scholarship and print at the service of counter-reformation Catholicism positions him to the forefront of Irish cultural history in the early seventeenth century’ (Caball, p.272). A most important work, and probably its only obtainable edition.

ESTC T180574. This ed. not in Best, Bibliography of Irish philology and of printed Irish literature. L. Ferlier, ‘An Teagasg Criosdaidhe (1707)’, Jesus College Libraries (online, 2015); S. Ryan, ‘Bonaventura Ó hEoghusa\\\'s \\\"An Teagasg Críosdaidhe\\\" (1611/1614)’ Archivium Hibernicum, 58 (2004), pp.259-67; E.W. Lynam, The Irish Character in Print 1571 to 1923 (1968); M. Caball, ‘Articulating Irish identity in early seventeenth-century Europe’, Archivium Hibernicum, 62 (2009), pp.271-93.