MISSAL, Use of Sarum

Missale ad usu[m] insignis ac preclare ecclesie Sa[rum]

London, p[er] Richardu[m] Pynson, [1512]£49,500.00

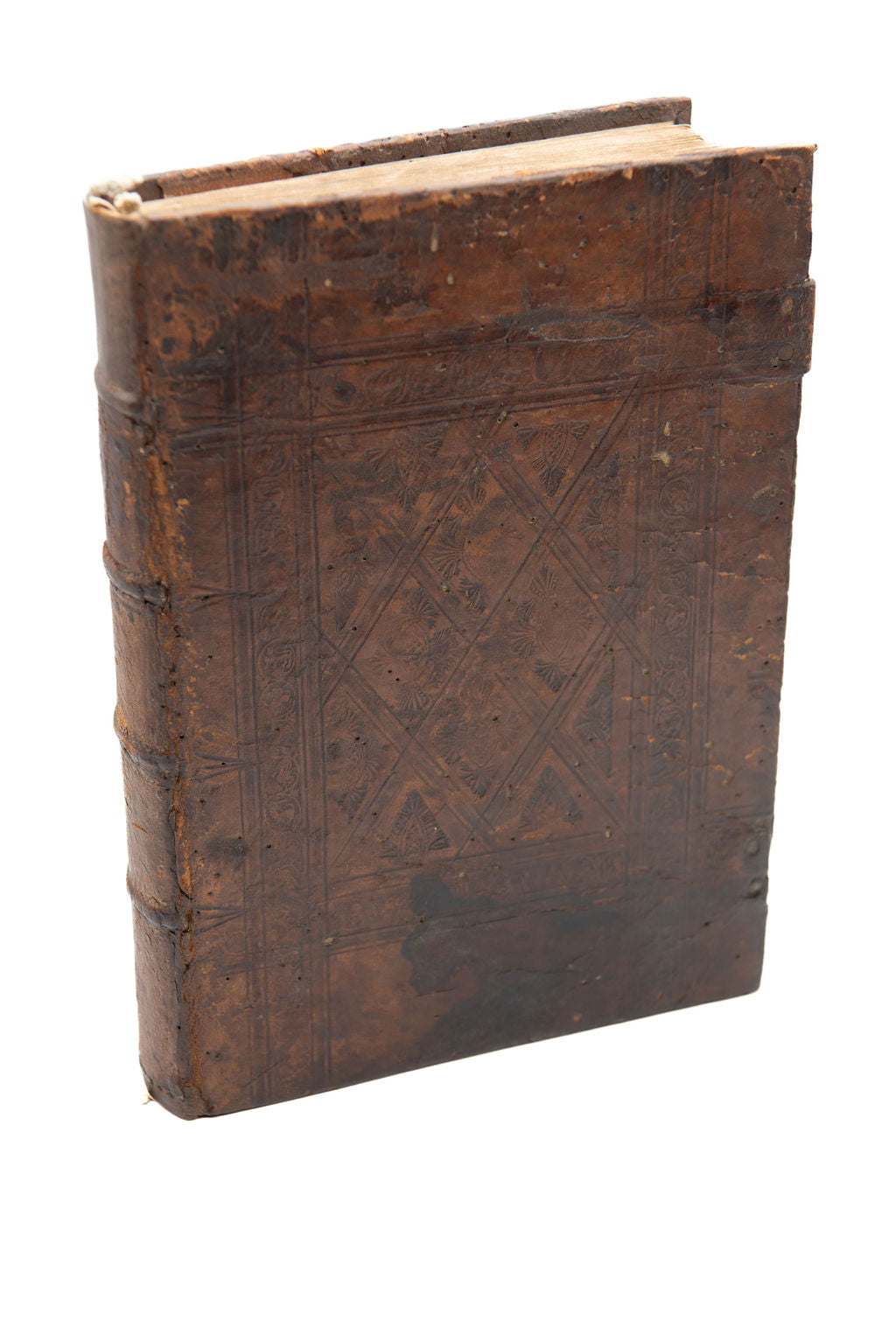

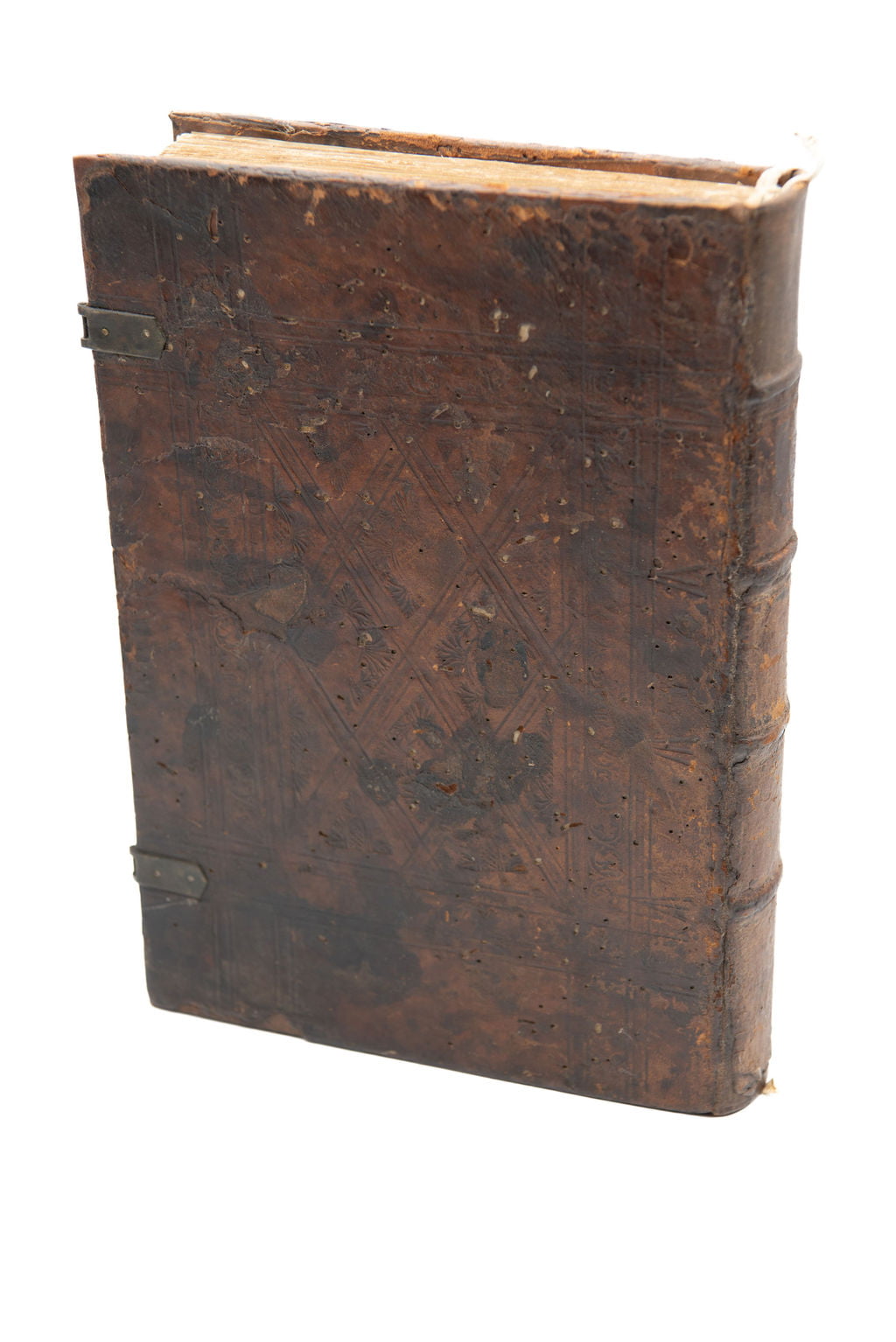

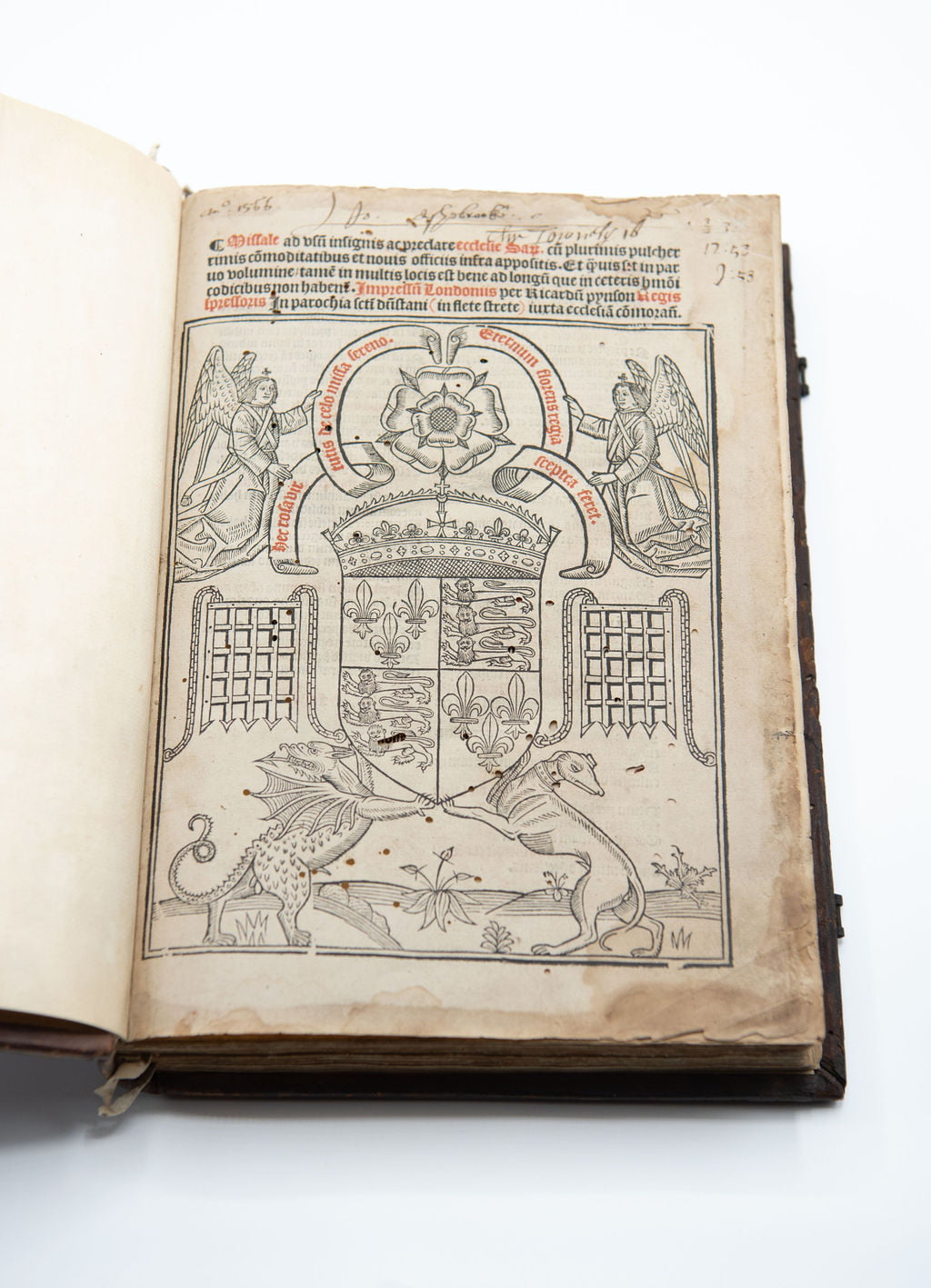

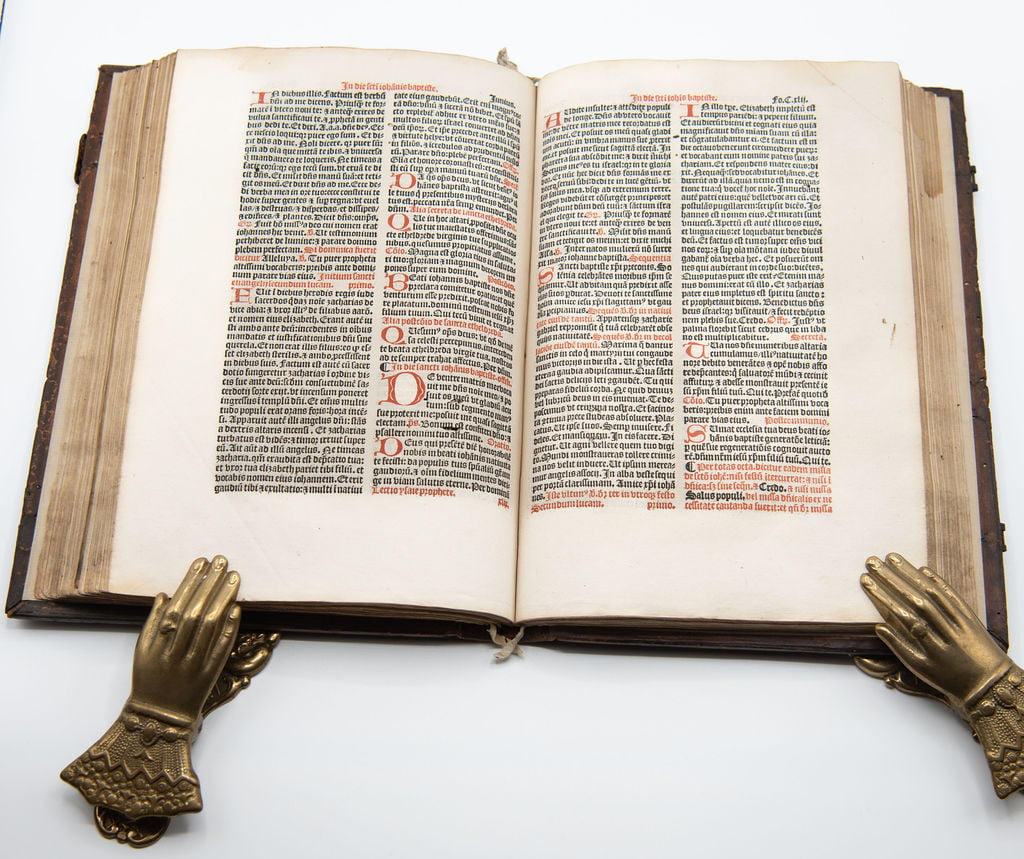

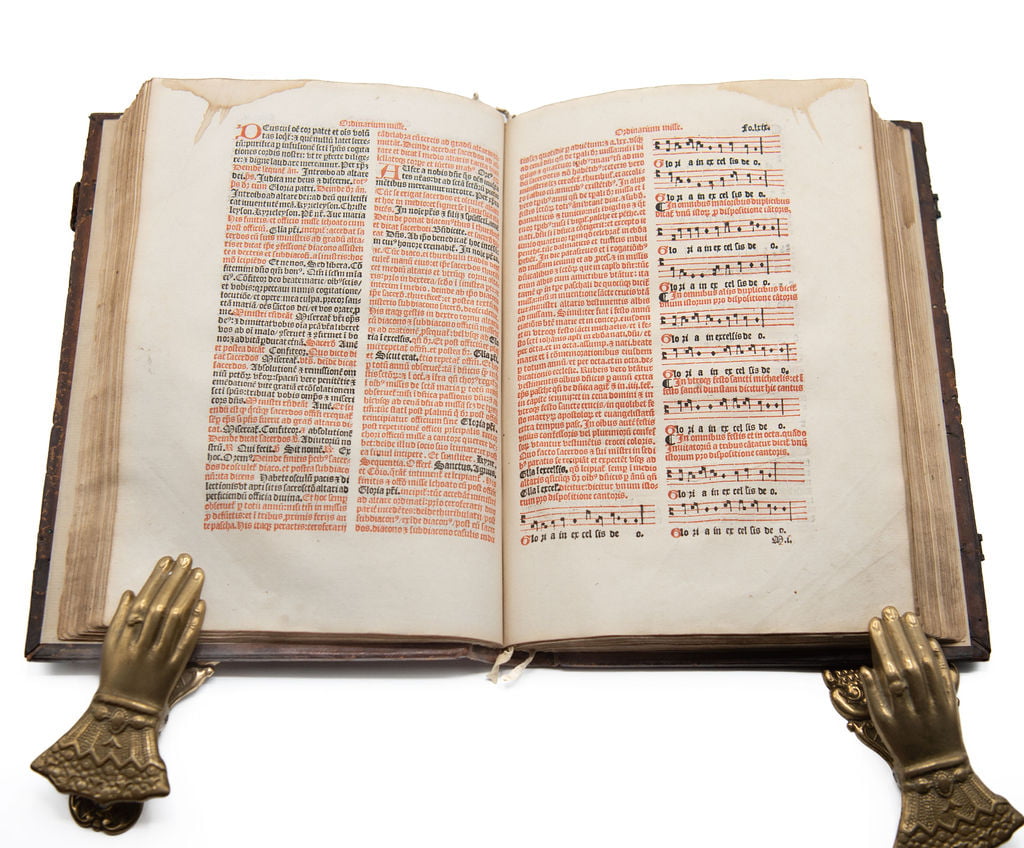

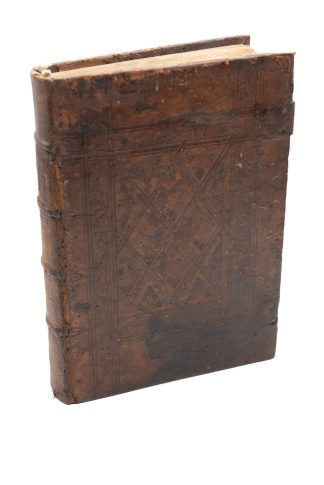

Folio. ff. [viii], Clxxvi, xliiii, [xvi]. lacking CC2-5 (four leaves). Gothic letter, printed in red and black throughout, typeset music. T-p with fine near full page woodcut of the royal arms, angels above, griffin and greyhound below, fine woodcut initial H at the beginning with royal insignia, woodcut historiated white on red initials, full page woodcuts of the crucifixion and Christ in majesty, column width woodcut of St. Andrew, two leaves of the Canon of the Mass (N3-4) printed on vellum, Pynson’s woodcut printer’s device on verso of last, some contemporary marginalia,‘John Ashebrooke’ autograph on title dated 1566, with his inscription on vellum leaf N3r, Christopher Townely (probably the antiquary, 1604—1674, signature on title), Cosmo Gordon autograph on front flyleaf dated 1938, Robert S Pirie’s bookplate on pastedown. Scattered single worm holes in first fifty leaves and last few quires, light mostly marginal waterstains in places, larger and heavier on last few quires, small single worm trail in blank upper margin of quire A at end. A very good copy, on thick paper with excellent margins, in contemporary, probably Oxford calf, covers triple blind ruled in a panel design, outer frame with a charming blind roll of alternate animals, (Oldham AN. m (i) 571), central panel triple blind ruled in a diaper pattern with blind ‘pineapple’ stamps (Oldham A (4) 962), rebacked with most of the original spine laid down, endpapers renewed, surface worm holes, a few scratches, in a brown cloth drop-box.

A extremely rare edition of the Salisbury Missal, one of the very few examples of an English printing of the work. An exceptional survival in remarkable contemporary binding. “The English printers of the fifteenth century seemed curiously reluctant to print the major service-books of their own national liturgy, the rite of Sarum. This apparent disinclination cannot be explained by any lack of a market for such works. The Sarum Missal, above all, was certainly in greater demand than any other single book in preReformation England, for every mass-saying priest and every church or chapel in the land was obliged to own or share a copy for daily use. Yet it is a striking fact that of the twelve known editions of the Sarum Missal during the incunable period all but two were printed abroad, in Paris, Basle, Venice, or Rouen, and imported to England. The cause of this paradoxical abstention was no doubt the inability of English printers to rise to the required magnificence of type-founts and woodcut decoration, and to meet the exceptional technical demands of high-quality red-printing, music printing, and beauty of setting, which were necessary for the chief service-book of the Roman Church in England. Caxton and Wynkyn de Worde at Westminster, John Lettou and William de Machlinia in London, Theodoric Rood at Oxford, and the Schoolmaster Printer at St. Albans, possessed neither materials nor craftsmen fit for this specialized work. Their chosen, natural, and economically profitable field lay in the provision of English vernacular texts or other matter in local demand. They performed this task, for the most part, with a sturdy indifference to Continental refinements, indeed with a peculiarly national character and individuality, which we may admire and relish to this day. Meanwhile the great book-producing centres of Italy, Germany, and France (subject to their own specializations and rivalries) abundantly supplied England and other outlying countries with service-books and all other works – such as the classics, the Latin Bible, scholastic theology, Roman and Canon law, medical and other sciences – which were in international demand. English printers had no incentive to compete with these, and we may be almost glad of it, for they would have risked losing the insular savour of their national identity.

The exceptions .. only go to prove the rule. The printers Julian Notary and Jean Barbier, who signed a Sarum Missal commissioned by Wynkyn de Worde at Westminster on 20 December 1498, and Richard Pynson, who completed another on his own behalf in London on 10 January 1500, were French by nationality and training, and used imported Parisian liturgical type-founts in these volumes, which in general appearance and quality are hardly distinguishable from the best missal-printing of Paris or Rouen. True, Notary and Barbier baulked at the difficulties of complete music printing, and supplied only blank printed staves for musical notes to be added in manuscript. Pynson, whose edition [of 1500] is remarkable as containing the first true English-printed music, must surely have brought in from Paris or Rouen not only a supply of music type, but also an expert music compositor.

The sixteenth century brought little change. In a total of forty-eight editions of the Sarum Missal from 1501 to 1534 (the year when the final break with Rome was signalized by Henry VIII’s Statute of Supremacy) twenty-six were printed in Paris, sixteen at Rouen, two at Antwerp, and only four in London. Three of these last were produced by the competent and enterprising Pynson, in 1504, 1512, and 1520, and only one, which is known only from a fragment of four leaves, by Wynkyn de Worde, in 1508. After 1534, except for a brief reappearance in 1554-7 under Mary Tudor, when five editions were produced (two at Rouen, one in Paris, two in London), the Sarum Missal was printed no more. Existing copies seemed useless or even damnable, except to a clandestine few, their possession became dangerous to life or liberty, and nearly all were destroyed by fire, or neglect, or used as waste paper. In our time, when men value them again at last for their sanctity, or beauty, or as monuments of religious or printing history, or as bibliographical marvels, these missals are rare indeed. Of the twelve incunable editions three exist only in unique copies, three in two copies, and only one in as many as six copies; indeed, it seems statistically likely from these low survival figures that other editions may have been entirely lost or, at best, await discovery.” George D. Painter. ‘Two Missals printed for Wynkyn de Worde.’

An exceptionally rare work, very finely printed with some of the earliest printed music in an English book, in a beautiful contemporary Oxford binding.

STC 16190 (ESTC lists 7 copies at least / BL & Cabridge U.L. incomplete); Weale-Bohatta 1417; Steele, The Earliest English Music Printing, 8.In stock