GOWER, John.

IN CONTEMPORARY BINDING

De Confessione amantis.

London, Thomas Berthelet, 1554.£42,500.00

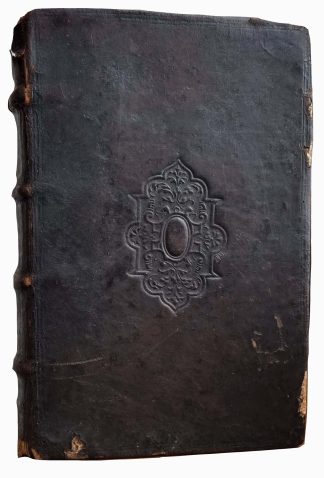

Small folio. ff. [6], CXCI, [1, blank]. Black letter, double column. Title within woodcut border with geometrical decoration, putto and grotesque, decorated initials. Intermittent light water stain to upper outer blank corner of first two gatherings, one or two small clean worm holes to lower blank margin of first half, occasional minor marginal thumb or ink marks. A fine copy, crisp, well-margined and unsophisticated, in near contemporary English (probably London) calf, vellum used as spine lining (stubs visible), double blind ruled, blind-stamped arabesque centrepiece to covers, raised bands, extremities rubbed with a little loss at head and foot of spine, and to cover edges. Booklabel of K. Rapoport to front pastedown, early ms ‘v / m’ (binder’s instruction?) to ffep verso, C17 ms bibliographical note to title verso, ms marginalia to two ll. and ‘f:145:p:2’ to rear pastedown, in the same hand.

Fine, unsophisticated copy, virtually unpressed, of the third edition of this milestone of medieval English poetry (despite its Latin title), once as successful as ‘The Canterbury Tales’ and ‘Piers Plowman’. What is known about the life of John Gower (1330-1408) comes mostly from his works, written in French, Latin and English, employing allegory to tackle moral, religious and political questions. His English vocabulary shows Kent and Suffolk influence. This edition of the ‘Confessio’ – his most successful work – is a close reprint of Berthelet’s (1532), based on a ms collated with Caxton’s edition. (Pforzheimer II, p.411). Berthelet’s dedication to the reader is a literary essay which explains how the work originated, i.e., from a conversation with King Richard II in the 1380s; it also ‘canonises’ Gower by mentioning his acquaintance with Chaucer, who dedicated his ‘Troilus and Criseyde’ to him, and his rich tomb at Southwark Cathedral.

The Prologue summarises Gower’s desire to produce a book ‘somewhat of lust, and somewhat of lore’, to elicit the interest of a varied readership. Like Boethius’s ‘De Consolatione’, it is a work of consolation and meditation; like Chaucer’s ‘Canterbury Tales’ and Boccaccio’s ‘Decameron’, it presents a myriad of delightful, short exemplary stories on sundry topics, populated by interesting characters. The narrative frame is the confession of an ageing lover to the chaplain of Venus, the epilogue being assigned to the goddess herself. The short stories are told by the confessor to explain moral points during their conversation: e.g., against arrogance, lust, sexual violation or vain glory, and in defence of chastity and continence. For instance, one tells the story of King Antiochus’ incestuous passion for his own daughter, whom he violated after his wife’s death. Interestingly, Part VII is devoted to the best ‘regimen sanitatis’ according to Aristotle, the well-being of the soul linked to the well-being of the body. It includes a verse summary on the subcategories of philosophy, including music and mathematics, the elements, humours, organs, terrestrial geography, the planets, zodiac and constellations. The c1700 annotator wrote an amusing comment on Gower’s description of the horses pulling the Sun’s cart through the heavens, suggesting ‘it may be he [Apollo] has got a new set of horses since Ovid’s days’ to highlight a discrepancy with the source. He also glossed two pages on stars and their corresponding minerals and herbs, marking the herb called ‘Annabulla’ (i.e., Annabella, sage) as probably ‘an allusion of the printer’s to H[enry] 8[th]’s time’.

ESTC S120946; Pforzheimer, 422; STC 12144.